Introduction

Children were particularly vulnerable during the Holocaust. Deemed as "unwanted," a threat to future Aryan domination, and too small to be of use to the Nazi war machine, children were killed first in aktionen. The Germans and their collaborators killed more than one million Jewish children during the Holocaust, in gas chambers, upon birth, with malnutrition, and with improper clothing and shelter for extended periods of time. Despite the young ages of these victims, many of them sought to live and remain hopeful in spite of an impending doom. Both the surviving children, as well as the victims have left a legacy that can still teach and inspire into the twenty-first century.

The ruthlessness of Nazi rule and the barbarities of war forced some children to mature beyond their years. Many children took on responsibilities that are normally associated with adults, because of the traumatic and devastating circumstances in which Jews were forced to live under Nazi occupation. They made difficult choices that often affected the future of their families, such as the decision to smuggle food, which could result in death. Not only did children have to accept life without school and playgrounds, but they were often not even allowed to act like ‘children' at home. Some lived in overcrowded conditions, without proper room to play and develop as noted in the Declaration on the Rights of the Child adopted by the League of Nations in 1924. Many avoided deportation by hiding and keeping silent for days as a time. It is important to emphasize the fact that parents were also not able to properly care for their children under these circumstances. This is often a subject overlooked when teaching the subject of the Holocaust.

Of course there were also children in hiding, some of whom assumed alternative identities and maintained relatively normal lives as they went to school and tried to make new friends. Others kept silent for years at a time, sometimes in small, dark spaces. Regardless of the circumstances, and in spite of the deliberate attempt to murder them, children during the Holocaust demonstrated resilience, even if they ultimately perished.

Why Teach About Children During the Holocaust?

Teaching about children during the Holocaust allows younger students to learn and empathize with people roughly their age, at a stage of life to which they can relate; almost any lesson that is taught on adults during World War II, may be taught about children as well. They too went into hiding, emigrated as refugees, were forced to move into ghettos, were shipped in boxcars to death camps, stood in line to be "selected," and sent to their deaths. There were also non-Jewish children whose parents chose to rescue Jews, greatly affecting their lives as well.

Most importantly, stories of children in ghettos can provide teachers with new approaches to teaching this subject. Children are symbols of hope, representing continuity and the future. However, for the purposes of this newsletter, emphasis is placed on children's creativity in the face of evil. They designed magazines, painted, wrote poetry, and sought independence much like contemporary youth. Their artwork and creations are excellent educational tools for teaching children as well as adults.

Petr Ginz

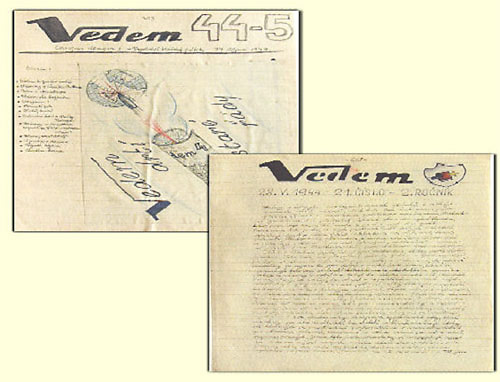

For example, Petr Ginz, born in Prague in 1928, spent his adolescence in the children's home in the Theresienstadt ghetto. He was remarkably talented at writing and drawing and edited the youth newspaper Vedem ("We are the Leaders"). He was murdered in Auschwitz-Birkenau in the fall of 1944. Petr kept diaries from 1941-1942 and then while he was in Theresienstadt. These diaries were published in the The Diary of Petr Ginz 1941-1942 (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2004) by his sister who survived the Holocaust and moved to Israel. The Diary of Petr Ginz 1941-1942 includes his entries, poems, and artwork. Teachers may wish to use all or parts of his diary in the classroom, to teach about the unique stories and lessons of children during the Holocaust. In 1942, Ginz wrote the following poem, reflecting on Nazi anti-Jewish legislation.

A Jew and An Aryan / Petr Ginz

Today it's clear to everyone

Who is a Jew and who's an Aryan,

because you'll know Jews near and far

By their black and yellow star.

And Jews who are so demarcated

Must live according to the rules dictated:

Always, after eight o'clock,

be at home and click the lock;

work only laboring with pick or hoe,

and do not listen to the radio.

You're not allowed to own a mutt;

barbers can't give your hair a cut;

A female Jew who once was rich

can't have a dog, even a bitch,

she cannot send her kids to school

must shop from three to five since that's the rule.

She can't have bracelets, garlic, wine,

or go to the theater, out to dine;

she can't have cars or a gramophone;

fur coats or a telephone;

she can't eat onions, pork or cheese,

have instruments, or matrices;

she cannot own a clarinet

or keep a canary for a pet.

rent bicycles or barometers;

have woolen socks or warm sweaters.

And especially the outcast Jew

must give up all habits he knew:

he can't buy clothes, can't buy a shoe,

since dressing well is not his due;

he can't have poultry, shaving soup,

or jam or anything to smoke;

can't get a license, buy some gin,

read magazines, a news bulletin,

buy sweets or a machine to sew;

to fields or shops he cannot go

even to buy a single pair

of winter woolen underwear,

or a sardine or a ripe pear.

And if this list is not complete

there's more, so you should be discreet;

don't buy a thing; accept defeat. [...]

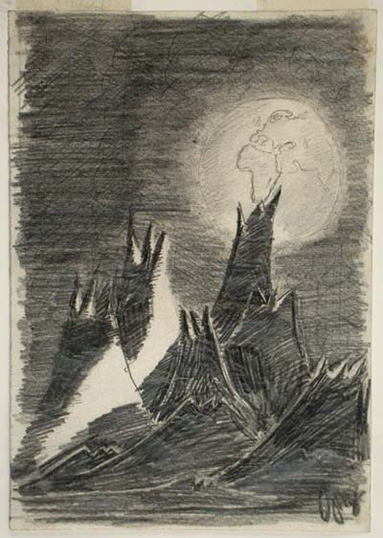

Petr Ginz (1928, Prague – 1944, Auschwitz-Birkenau). Moon Landscape, 1942 -1944

Petr Ginz's Moon Landscape

In 2003, Ilan Ramon, the Israeli astronaut that perished in the doomed US space shuttle Columbia, took this drawing with him from the Yad Vashem collection.

Diary Entry – November 28, 1941

"The geography teacher Mr. David got married (probably yesterday), so our class bought him a kerosene cooker, Primus. It costs 80 crowns, which amount was collected by our class (IV.B) (in fact we collected 120 crowns; 40 crowns went into the class fund). I wrote a poem to go with it and both were gift-wrapped, but Mr. David was at the registration so we can only give him the present on Monday."

From an Article by Petr Ginz in Vedem Magazine – 1944

"Deprived of our former sources of culture, we shall create new ones. Separated from the sources of our old happiness, we shall create a new and joyfully radiant life!"

Similar to the resources presented here, teachers may be interested in drawing upon a variety of resources to teach about this difficult subject matter. Primary source materials highlight the voices of the Jewish children who lived during this period, what they felt, how they sought to live in the face of death.

Additional Resources

- I Never Saw Another Butterfly, by Hana Volavkova. New York: Schocken Books, 1993. A compilation of children's drawings and poems from Terezin camp.

- We Are Children Just the Same: Vedem, the Secret Magazine by the Boys of Terezin, by Kurt Jiri Kotouc, Zdenek Ornest, Marie Rut Krizkova, and R. Elizabeth Novak. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1994. This book takes pieces of a magazine printed by teenage boys imprisoned in Teresienstadt.

- The Diary of the Vilna Ghetto, by Yitskhok Rudashevski. Tel Aviv: Ghetto Fighters' House, 1973.

- The Diary of Eva Heyman, by Eva Heyman. New York: Shapolsky Publishers, 1988.

- We Are Witnesses, by Jacob Boas. New York: H. Holt, 1995.

- Youth Writing Behind the Walls: Avraham Cytryn's Lodz Notebooks, by Avraham Cytryn.

- The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak, Five Notebooks from the Lodz Ghetto, edited and with an introduction by Alan Adelson. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.