Introduction

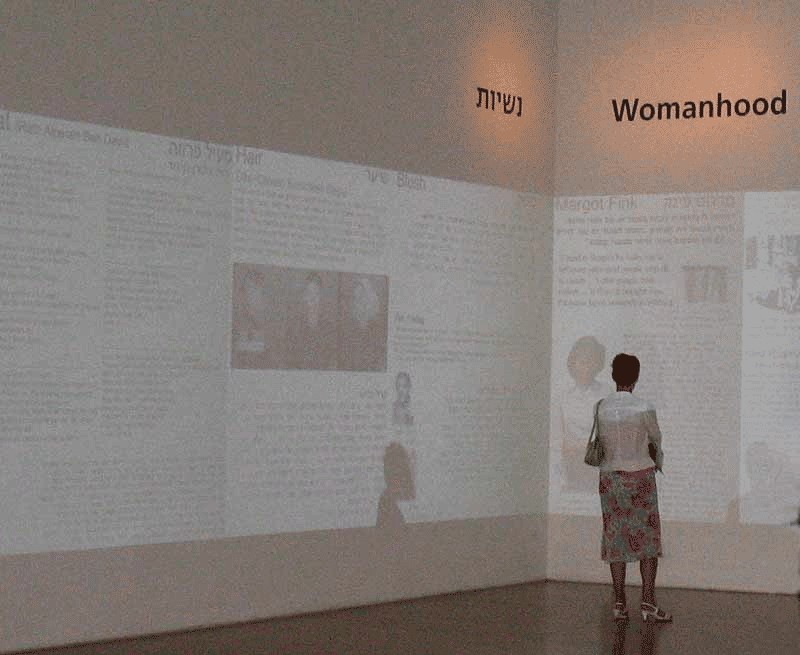

This exclusive interview was published in our newsletter Teaching the Legacy (January, 2008). The original interview, conducted in Hebrew, first appeared in our Hebrew edition of October, 2007. Ms. Inbar discusses the exhibition "Spots of Light: Women in the Holocaust", which she curated and displayed at Yad Vashem's art museum. A respected writer, editor, and lecturer, Ms. Inbar further elaborated on the theme in the printed catalog and in her essay to introduce the exhibition and its purposes. Her experience as Director of the Museums Division at Yad Vashem led her to make bold presentation choices that revealed complexities in the area where history, emotion, and personality meet.

"Women have a special story which doesn't fully come across in the general Holocaust narrative"

Yehudit, thank you for agreeing to be interviewed for Teaching the Legacy. Our subject is the exhibition "Spots of Light: Women in the Holocaust". Please tell us about the decision to launch this exhibition.

Even as we were working on founding the historical museum, we felt that women have a special story which doesn't fully come across in the general Holocaust narrative, which is a more male-oriented narrative. It wasn't that there weren't women in the museum – certainly there were – but I felt their story could be told separately, in a different light.

I believe the same can be done with the men's story – showing it in a different light, while stressing aspects that today are not part of the central Shoah [Holocaust] story.

So why focus only on women?

The subject is one that's close to me personally. My three aunts were murdered in the Holocaust. I come from a home with three sisters and I have three daughters and a granddaughter. Gender and feminist issues are close to my heart. In my opinion, [these issues should be] important to everyone. Looking back, I can say without a doubt – based on the responses from female survivors and their daughters – that we were correct in assuming there were certain aspects of the Jewish women's experience that had not been highlighted in the past. [...] After seeing the exhibition, many of the female survivors said that they felt their story had been rectified. Before this exhibition, some of them had effectively stopped speaking about the Holocaust because they felt they were always being portrayed as victims.

"Something very profound in their outlook – has changed"

Today, they're proud to tell their story. Some of them have returned to presenting it publicly in various forums (at the International School for Holocaust Studies, etc.). Some of the women whose stories have been featured in the exhibition are members of a large survivors' group that meets every year. After visiting the exhibition, they told the others in the group about it, and said it was their true story – not [just] the victimization that had previously been portrayed.

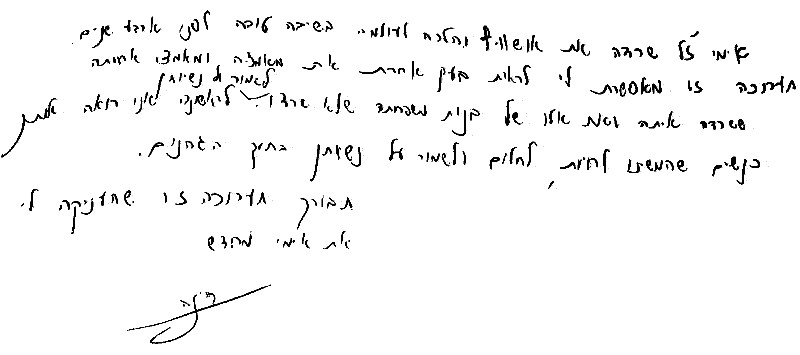

Every holiday, I still get calls from them telling me that something very profound in their outlook – in the way they see themselves – has changed. They are no longer victims, but rather women who had fought a legitimate, positive struggle for survival. After seeing the exhibition, many second-generation women, whose mothers had already passed away, felt proud of them for the way they had struggled to survive. For example, one of the visitors wrote:

My mother, of blessed memory, survived Auschwitz and lived a good, long life, passing away four years ago. This exhibition allows me to see the efforts of her and her sister in maintaining their femininity – as well as those female members of my family who did not survive – in a new light.

For the first time I see them as women who continued living, dreaming, and preserving their femininity while in hell.

Bless this exhibition for giving me my mother again,

Rina

What is it about the exhibition that made Holocaust survivors and their daughters feel this way? How is its presentation different from the way women in the Holocaust are usually portrayed?

I think that on the one hand, the exhibition deals with the most basic aspects of life, and on the other hand – with issues that have never been touched upon, because they were seen as either peripheral or almost contemptuous. This was because they had never really been part of the narrative of the Shoah which is, as I've said, primarily male-oriented.

"The power to create something from nothing is an act of choosing life"

"Femininity and the Holocaust" seems almost a contradiction in terms, yet this is a very basic part of the female personality, regardless of context. Furthermore, this was a survival tool of the highest order, which until today has been ignored within the discourse [of Holocaust research]. For instance, in the first section of the exhibition, we display a bra that a woman had sewn in a camp. This, seemingly, is a peripheral point; yet is, in fact, an astonishing act of survival. The entire process of creating this bra, after this woman had lost her entire family and her daughter, was a process of survival and emotional recovery. The power to create something from nothing is an act of choosing life. After all, this endeavor was almost impossible in a concentration camp: obtaining a piece of glass with which to cut the cloth, obtaining string, securing fabric. She also had help from other women in the camp. Finally, there was the pride in knowing she had managed to create something, achieve something that was almost impossible. This initiative was a kind of mental escape along with self-rehabilitation, a sort of breathing-tube to life, like a game or like imagination.

This discussion brings me to the connection between the women's exhibition and the "No Child's Play" exhibition. In the latter exhibition, which I created ten years ago, and that was designed for children, I chose the subject because I thought it would be attractive to children visiting Yad Vashem, and I did not realize its greater significance. I myself am very fond of children's games and toys, and the catalyst for the whole matter was speaking with my daughter, who was then young. When I first presented the idea at Yad Vashem I was told I wouldn't be allowed to display the exhibition here, because "during the Holocaust people were murdered – they did not play games". In fact, I was most fearful of survivors' reactions; yet after some initial surprise, they became very supportive and fond of the idea. When I first proposed it, they were almost shocked. Many of them had been children during the Holocaust and hadn't been in camps, hadn't worn the uniforms, and so they often felt like they were hardly part of the Shoah story, and were almost ashamed of their own stories. They claimed they hadn't played games at all during the Holocaust. It was only after they saw that I'm legitimizing this subject – they had never been asked about it, though its an important, worthy subject – that the stories began coming out. All of a sudden they began bringing me broken parts of toys that they had kept their entire lives in the back of their closets at home, and essentially – in the back of their memory. Suddenly, it was legitimate.

So in these exhibitions, you find a legitimacy to raise subjects that had not previously been considered "appropriate"?

Yes, certainly. After these two exhibitions, I can see today that subjects that had seemed secondary and peripheral, certainly next to the story of genocide, were actually much more significant. Imagination, creativity, game-playing, all these factors gave them the will and mental strength to endure another day in the horror that the survivors were going through.

"They wanted to share with the women around them, or pass on to the next generation"

Some research – mostly in the fields of psychology and sociology – indicate that escape from the horrors on the one hand, and the ability to create on the other, be it by imagination or by improvisation, have contributed to healthier mental survival during and after the Holocaust. Would you agree with this assertion?

Absolutely – because the method of survival usually wasn't individual but rather collaborative, involving other people. For example, the woman and the child – those that appear in the context of these two exhibitions I've mentioned – conducted positive, vital human interaction. Take cookbooks, for instance. I remember the scornful response I had encountered when the Theresienstadt Ghetto cookbook was published in the United States. Responses were along the lines of, "Why does it matter? Why are you dealing with such nonsense?"

While conducting research for the women's exhibition, I discovered that cookbooks were a widespread phenomenon during the Holocaust. The exhibition itself features over ten such cookbooks. An interest in cooking recipes appears throughout the Holocaust – in the ghettos, in hiding, in the camps, even in Auschwitz. In Auschwitz, when the women lacked paper to write on, they would yell the recipes to each other so they would remember [the ingredients]. The quantities, by the way, were highly exaggerated. This was a mental survival method par excellence. This was something that would bring up positive memories from the past; something that the women were proud of – their mothers had passed these recipies down to them, a tradition that they wanted to share with the women around them, or pass on to the next generation in case they themselves would not survive. In this sense, [passing on recipes] was like a last will and testament. Also, each woman would pass on her own local variant of recipes. This was an entire world of sensuous, feminine fantasies, a world of positive, creative escape, a world with hope for the future. They would either survive themselves or someone would at least receive the recipes – their daughters or someone else – but the female tradition was unbroken and would not be broken, even if they themselves were not to survive.

In this sense, the games on display at the children's exhibition – the children themselves may not have been thinking in terms of the future, more of the present, but playing was still an optimistic act. For instance, Uri Orlev. When you read his autobiography, you discover he lived in a rich, fertile fantasy world. He was king of the world, king of the jungle, the emperor of China, and while playing with his brothers he would rarely "come down to earth". This act was a survival technique of the first order.

In conclusion, do you think that Holocaust research is ready for exhibitions that raise these kinds of questions – questions that are not seen as central within the mainstream of the field?

In a certain sense we are not yet ready for an exhibition of this kind, because I think that the general message of the women was unequivocally: survival, survival, survival. They didn't deal with respect, nor heroism, didn't partake in ego wars. The energy they had was directed solely towards their own survival and that of those around them. This is their message to the world, and it's a positive message of choosing life. Within the chaos of the Holocaust, which [to us] is intrinsically associated with death and evil, this aspect is still difficult to absorb.