Liquidation of the Jewish Community in Munkács

A day before the evacuation of the Munkács ghetto, the Germans gathered all the Jews with beards and sidelocks and ordered them to destroy what was left of the famous Yeshiva of Rabbi Shapira, singing while they labored. The Jews carried out their task under a hail of lashes.

Deportation of the Jews of Munkács. The Jews walked with their possessions along Mihaly street, opposite the great theater. They were brought to the brick factory, from where they were deported.

The deportation of Hungarian Jewry to Auschwitz-Birkenau was meticulously planned. László Ferenczy, a senior gendarme officer, was appointed to command the deportation operation, and he fixed his seat of power in Munkács. In meetings held in the town on 8 and 9 May 1944, all the details of the deportation of Subcarpathian Rus' Jewry were settled, and written orders were sent to the mayors of those towns with ghettos and train stations.

The first deportation train left Munkács on 11 May. The deportation route and number of cars was predetermined: 3,000 people were to be evacuated on each train. The loading of the trains, carried out at a distance from the civilian stations, were overseen by a gendarme or German army officer, and the Jews were allowed to take with them just a few belongings.

On the nine transports that left the Munkács brick factories, 28,587 Jews from the town and its surroundings were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. According to data of the Hungarian train service in Kassa, the transports from Munkács passed through Kassa on 14, 16, 17, 18, 19 and 20 May, carrying Jews from the area.

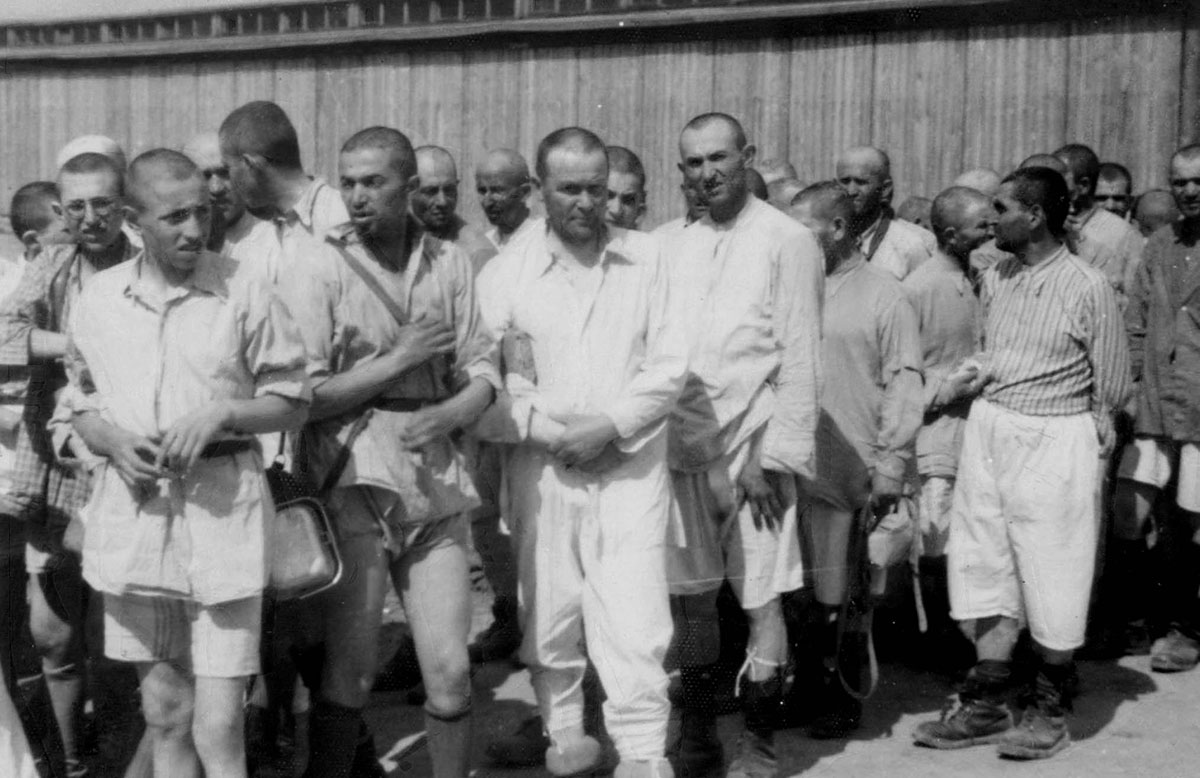

After 15 May, Jews from Munkács were brought from the ghetto to the brick factory, a five-kilometer walk away. Their passage was accompanied by abuse and violence: they were urged to walk faster and beaten mercilessly. When they arrived at the factories, the Jews were commanded to undress, and a thorough search of their clothes was conducted in order to rob them of their final possessions. The journey to the factories left many victims dead. The few days spent at the brick factories were marked by unceasing violence. Jews were forced to collect tefillin and talitot and burn them.

“Heraus, schnell, verfluchte Juden!” [Out! Quick! Damned Jews!]. The whip hissed, thrashing the air, falling on our shoulders and heads, beating us out of our homes […] we walked slowly, or were rather pushed ahead, accompanied by shouting, curses, and beating […] we reached the market square, which was by then crowded with frightened people, mothers cluthing their babies, men and women, children and old people… From that moment on we no longer had names – they counted us like cattle […]”.

(Rachel Bernheim, Earrings in the Cellar, Growing Up in Ruined Worlds, p. 50)

The remainder of the Jews of Munkács was sent in three transports that passed through Kassa on 21, 23 and 24 May, to the same destination – Auschwitz-Birkenau. The Jews were forced onto the deportation wagons under a hail of physical and mental abuse. They were pushed into the cattle cars, 70-80 people in each enclosed car, with one bucket of water for a three-day journey and one bucket to use as a toilet, with no fresh air or space to lie down. Some died along the way. Some committed suicide. Others lost their minds.

"We travelled in the cattle cars for days and nights, without enough toilets, men and women together, no air to breathe – just a small window of light. The train pulled us along, and nobody knew our destination. There were no stops. We arrived at night before a gate lit up like daytime, with the sign "Work will set you free" set above it. We had arrived at hell – Auschwitz, in the shadow of the crematoria.

During one selection, the adult women were set apart. In another, the older women were separated from the younger ones. We were promised that we would see each other the next day. We soon learned the truth: that same night they were all burned in the flames of the crematoria that worked day and night".

(From the testimony of Rachel Bernheim)

The Jewish Response

Jewish resistance in Hungary as a whole mainly consisted of rescue operations carried out by individuals and organized bodies. The Jews of Munkács smuggled food to their fellow Jews from the surrounding areas imprisoned in the brick factories, and sometimes also managed to smuggle food into the ghetto.

The Zionist youth movements in Munkács also carried out underground activities. Emissaries from these movements who came to the town from Budapest dealt mainly with smuggling young people to Budapest, Slovakia and Romania, but most were struck by the inability of Munkács Jewry to grasp the truth about the ghettoization process and the destination of the deportees. In addition, young people found it hard to leave their families, and escape itself was fraught with mortal danger.

The lack of active resistance in Munkács, like other places across Hungary, stemmed from the fast pace of anti-Jewish legislation in the country, the vast numbers of young men conscripted for forced labor, and the hope of a speedy liberation by the Red Army.