History of the Monastir Community Until 1941

Members of the Jewish Mandolin Orchestra on a hike, December 1929

The Emigration Movement

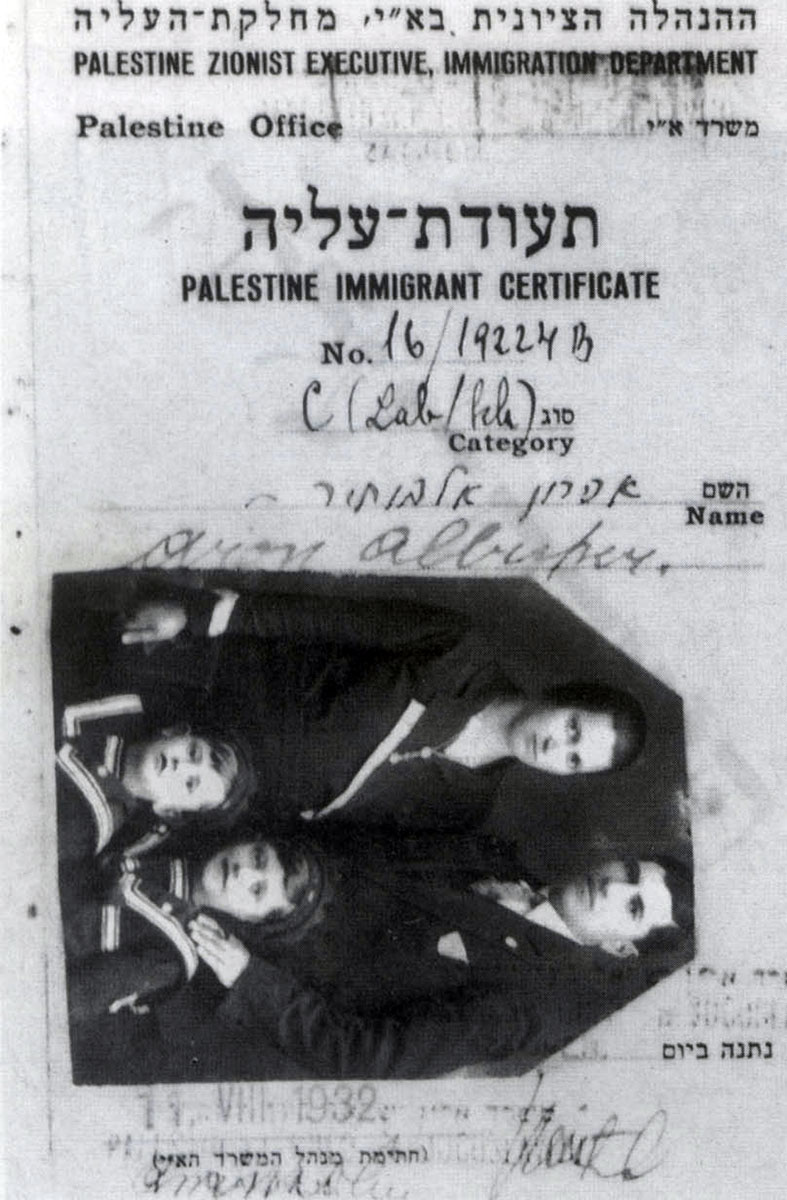

In the first decade of the 20th century, there were some 11,000 Jews in Monastir, about one sixth of the local population. However, from the beginning of the century, the community suffered from economic distress and overcrowding, and many chose to emigrate, some remaining within Yugoslavia, and others across the ocean to the US, Chile, Israel and Greece – mainly Salonika.

Rabbis

In 1913, with the annexation of the city to Serbia, a young rabbi from Jerusalem was invited to Monastir. Rabbi Dr. Ariel Ben-Zion, whose family had been exiled from Spain, had completed his scientific studies in Germany, and his arrival blessed the community with the leadership of one of the principal figures in Sephardic Jewry.

After the First World War, Yitzhak Elizafan, a notable teacher and cantor in Monastir, established Lomdei Torah, an educational-halachic institution for youth. Lomdei Torah staged Zionist-Nationalist performances in Hebrew written by Elizafan, and on Jewish holidays, its students would parade in the streets of the city, dressed in cloaks and hats, singing Hebrew songs. Elizafan emigrated to Eretz Israel in 1932.

In 1924, Rabbi Shabtai Ben Yosef Djaen was appointed chief rabbi of the community. Rabbi Djaen strongly encouraged his flock towards Zionism. Some of his actions were considered revolutionary; for example, the removal of the iron screens from the synagogue’s women’s section, and the bringing in of female teachers and kindergarten staff from Eretz Israel. Rabbi Djaen also established a food kitchen for the needy, and when he saw that the locals were using tombstones from the Jewish cemetery for building material, he collected enough funds to erect an iron fence around the cemetery, ornamented with Stars of David. Rabbi Djaen served until 1928, when the World Organization of Sephardic Jewry sent him to South America.

Rabbi Avraham Ben Moshe Romano, the last chief rabbi of Monastir, arrived in the city in 1931. Rabbi Romano made great endeavors on behalf of the community, which by then was in a dangerously low economic and social situation due to the unrest in the Balkans – destructive wars, changes in government and economic distress that caused 1,090 Jews to emigrate from Monastir in the 1930s. In March 1943, Rabbi Romano was deported with his community to Treblinka, where he was murdered.

Synagogues

The two synagogues – Il Cal Di Aragon and Il Cal Di Portugal – were not large enough to accommodate the number of congregants. Over the years more prayer houses were built or spaces were cleared in private homes, mostly as a result of donations by members of the community. Among these were the Shlomo Levy Synagogue, the Ozer Dalim Synagogue, and more.

Education

In the interwar period, education in Monastir was similar to that practiced in other cities across the country, with 12 grades in state schools, of which four were elementary and eight high school. At the time, only a few families could afford to send their children to high school, and at the age of 10 most children left the educational framework to help support their families: the boys as apprentices to craftsmen, and the girls as laundresses and housekeepers. In 1924, the first female kindergarten teacher from Eretz Israel, Leah Ben David, arrived in Monastir to help prepare the children for aliya (emigration to Eretz Israel).

Thus in the 1935-1936 school year, 625 Jewish children studied in the elementary schools, and 13 at the vocational girls’ school. At the end of the year, of the 625 elementary school children, only 20 signed up for high school.

In the 1939-1940 school year, a government decree was enacted to limit the number of Jewish children at state schools. As a result, 25 Jewish students were removed from school.

Life in the Jewish Quarter

The Jews of Monastir lived along the Dragor River in a quarter without a surrounding wall. The quarter was divided into areas: La Bustanico, La Tavana, La Bomba, Los Corttijos, Ciftlik, and more. The first two alluded to the professions of the residents – fruit-growers in the first, and in the second, tanners. Los Corttijos (the courtyards) comprised one large courtyard surrounded by a continuous row of attached houses, each with its own small courtyard. Above almost every front door was a Hebrew inscription or the Hebrew year in which the house was built. Near the Jewish quarter was an area called Ciftlik (the farm), where underprivileged Jews lived in gloomy, neglected shacks.

Charity and Aid Organizations

Over the generations, charity and aid organizations were established in Monastir to help the needy of the community as well as in Israel.

In 1894, the “Ozer Dalim” organization was set up, with each member paying dues according to his or her ability. The poorer members made especially sure to pay their dues, so as not to lose their membership. When any member of the organization or his family fell sick, a doctor was ordered, medicines and foodstuffs were bought and, when necessary, hospitalization was paid for. In cases of serious illness, patients were sent to hospitals in Belgrade and Vienna. The Arueti family established a synagogue with the same name as the organization, and all funds received by the synagogue were transferred to the organization.

On Passover and the Jewish New Year, the “Malbish Arumim” organization, supported by the Jews of the town and emigrants to the US, provided clothing and shoes to destitute children.

The American Fund, set up by ex-Monastir residents in the US, was run by people chosen by the community. In 1924, the Fund bought equipment for the school and distributed it among needy children. Every day, the “Matanot LaEvyonim” organization (Minza Di Alivos Povris) provided some 200 orphans with a hot, meat meal. The Burial Society took care of the final respect paid to the deceased, and also contributed money to the community itself. The Jewish Women’s organization helped poor brides in particular, and Jewish professionals took care of protecting the rights of the less educated vis-à-vis city and state institutions. The town also had a branch of WIZO.

All these organizations operated until the German invasion in April 1941.