Youth Movements and Political Parties in Monastir

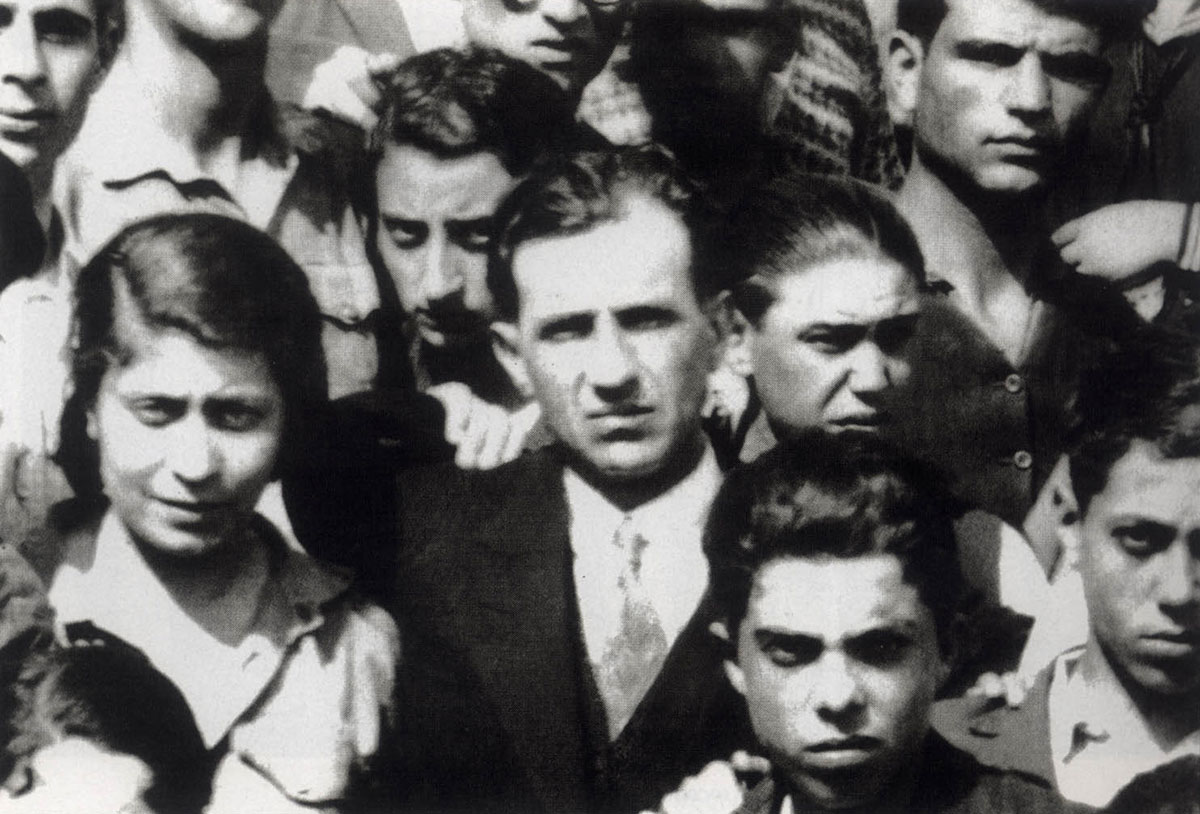

The Hebrew teacher Leah Ben David with members of the Maccabi Sports Club, Monastir, 1929

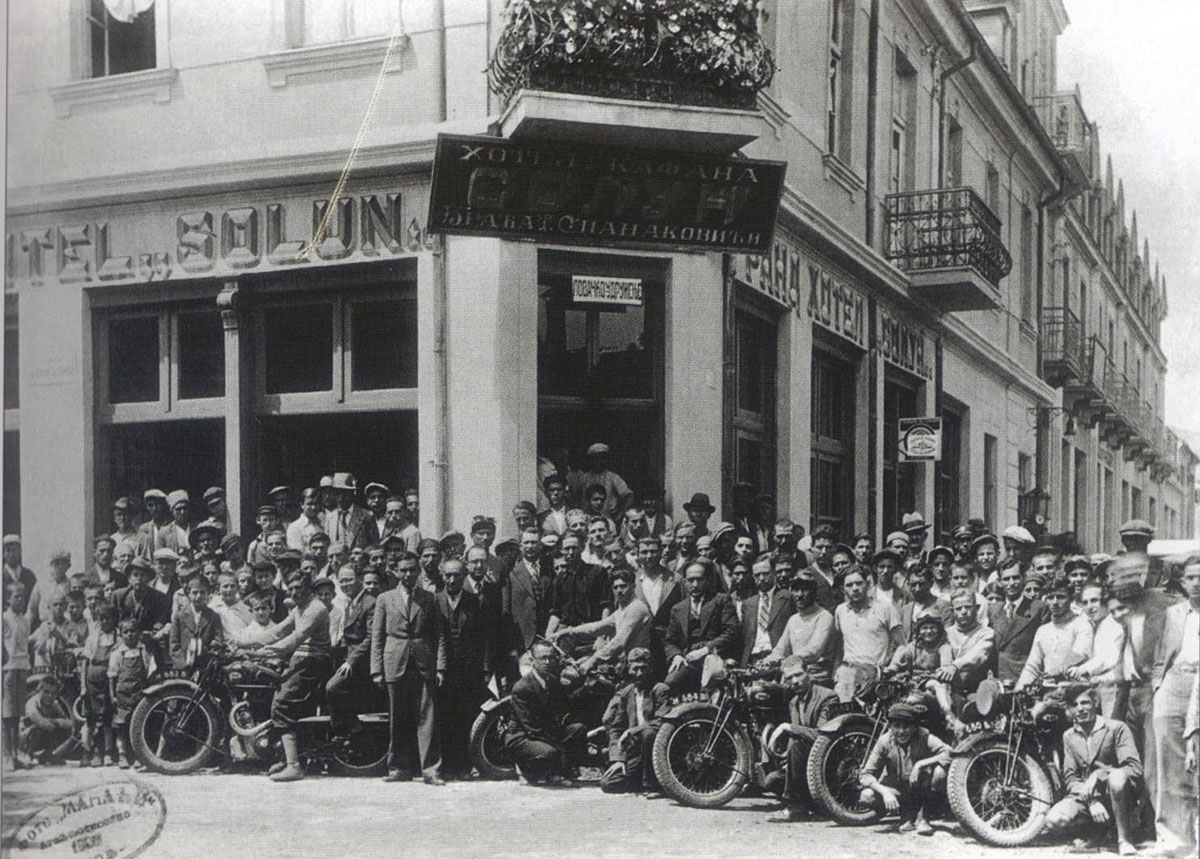

During the First World War, when the city of Monastir (Bitola) was bombed and turned into a battlefield, Leon Kamhi then just 17 years old, moved to Saloniki. It was 1917, and Kamhi, like many others at the time, was swept away by the wave of enthusiasm engulfing Saloniki in the wake of the Balfour Declaration. When he returned to Monastir, Kamhi initiated a range of Zionist activities. At the time, the Maccabi Movement was also operating in the city, but had not recovered from the hardships of war. In 1919, Kamhi established Zionist youth movements called Bnei and Bnot Zion. At the beginning of 1923, the two movements joined with Maccabi to form the HaTehiya movement with some 200 members, and Kamhi was chosen to head the united movement. That year, HaTehiya joined the SZO (the Union of Jewish Youth Organizations in Yugoslavia). Almost all of Macedonia’s young Jewish men and women were members of SZO.

Another Zionist organization in Monastir was Esperenze (Hope). The organization had an active football team, and its members learned Hebrew from the kindergarten teacher that had come from Eretz Israel, Leah Davidson (Ben David). A wind orchestra was also named Esperenze, after the Organization. The orchestra accompanied all the Zionist youth productions of the city and its surroundings. At the conference of southern Serbian cities held in Skopje in 1924, the orchestra escorted representatives from Monastir traveling to Skopje, marching and playing Jewish melodies throughout the streets. This parade aroused great pride among the Jews of Skopje, who gathered in the streets to meet the procession and accompany it with claps and cheers.

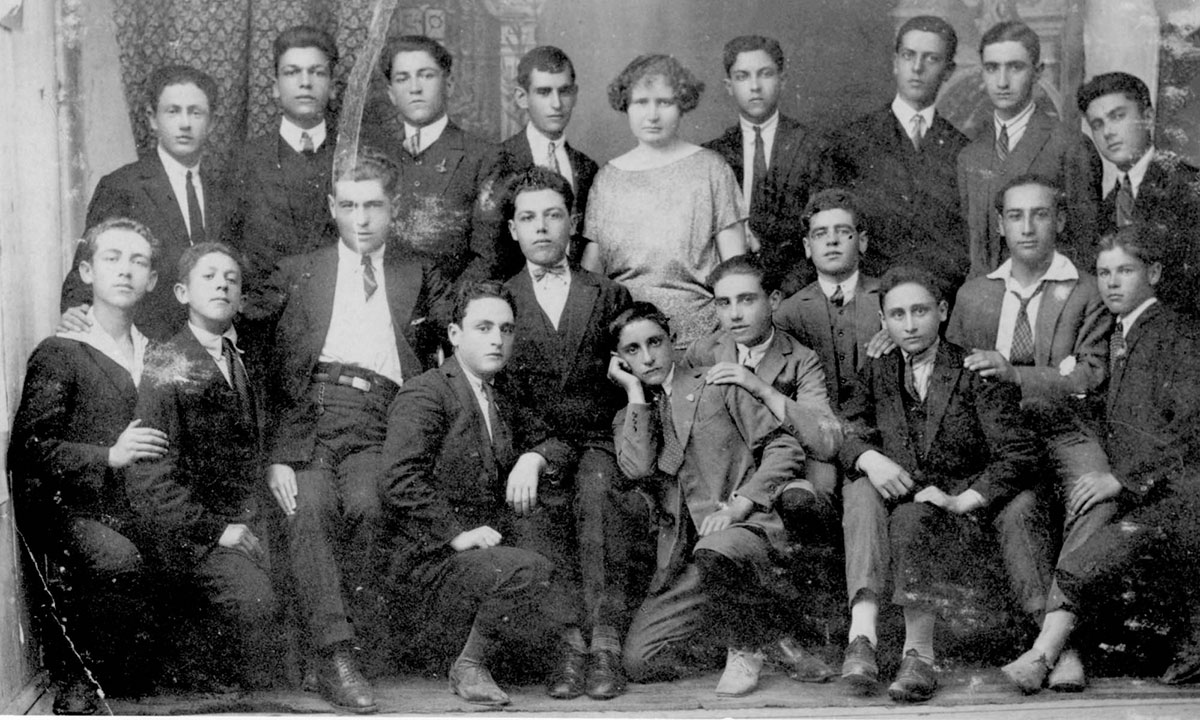

In 1931, a branch of the Hashomer Hazair youth movement was established in the city (known in Monastir as Shomrei Hamoledet), which, at the peak of its activity, boasted over 400 student members (also members of SZO). In 1932, Moshe Ashkenazi, an emissary sent from Kibbutz Merhavia, came to Monastir. Ashkenazi opened night classes in Hebrew for those wishing to emigrate to Eretz Israel, which almost every youth in the city attended. The Haganah also sent emissaries to Monastir. Many of the Hashomer Hazair members managed to fulfill their dreams and made aliya, where they joined Hashomer Hazair kibbutzim, notably Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakim and Kibbutz Gat.

The working youth were almost completely unrepresented in Hashomer Hazair, and they viewed this phenomenon as discriminatory. When Tchelet-Lavan (Blue-White, known in Monastir as Hadegel Haivri – The Jewish Flag) sent its delegates to the cities of Macedonia, they set up local branches to which many youth flocked. Tchelet-Lavan began activities in Monastir in 1934. After a short while, the branch had grown to more than 300 members. Like Hashomer Hazair, Tchelet-Lavan set up training farms in preparation for aliya. Groups of youth from Monastir set out for long months of training, most of them at agricultural farms organized by the Zionist Union of Yugoslavia; a few signed up for daily training sessions. This was a great opportunity for the young men and women of the city to meet other pioneering youth from across Yugoslavia. A few of the graduates from the training programs made aliya, the majority settling at Kibbutz Afikim in the Jordan Valley.

In the late 1930s, anti-government intellectuals – left-wing sympathizers and well known communists – gathered in Monastir. They managed to sweep up others in their enthusiasm, including many Jewish youths, especially from Hashomer Hazair. These youth joined the SCOJ (the Union of Communist Youth in Yugoslavia), but remained affiliated with Hashomer Hazair, believing that their attachment to SCOJ did not conflict with their affinity to a Zionist-Socialist organization. In August 1939, this assumption was put to the test with the signing of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, which aligned Communist Russia with Nazi Germany. The local Communist party, Jews from Yugoslavia, and in fact all those that identified with the left in Yugoslavia, were faced with a difficult dilemma. Some 800 members of Hashomer Hazair and Tchelet-Lavan were active in Monastir in 1939. Many of them were also members of SCOJ. Their dilemma grew as Yugoslavia affiliated with the Berlin-Rome-Tokyo Axis, at the outbreak of the war and after the occupation of Yugoslavia. The dilemma came to an end only after the German invasion of the USSR in June 1941.