History of the Monastir Community Until the 20th Century

The town of Monastir sat on an ancient road, the Via Egnatia, the shortest land route between the two Imperial Roman capitals, Rome and Constantinople.

The town of Monastir sat on an ancient road, the Via Egnatia, the shortest land route between the two Imperial Roman capitals, Rome and Constantinople.

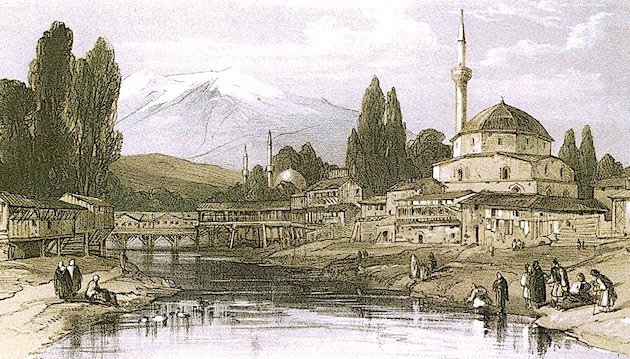

During 1381-1382, the Ottomans conquered Monastir, and turned it into a military fortress. Ottoman rule lasted until 1912, and the hundreds of years of Turkish administration left its mark on the Jews of the city.

At the end of the 15th century, Jews expelled from Spain settled in Monastir, where they encountered Romaniotic Jews – Jews that had been living in the area since the times of Ancient Rome. Refugees from the Iberian Peninsula continued to identify with the splendid culture of their countries of origin, and established separate communities in the Balkan cities not just according to their home countries, but also according to the regions whence they originated. They established two communities in Monastir, Aragonese and Portuguese, which for hundreds of years, until the Holocaust, kept separate synagogues, and suffered many disputes between them.

In the 16th century, Monastir contained some 1,500 houses, about 200 belonging to Jewish families. Some 200 years later, according to statistical information from 1889, Monastir had 31,257 residents, of which 5,500 were Jewish. The Jewish community of Monastir was in contact with other communities across the Ottoman Empire, especially that of Saloniki in Greece.

Economic Life

Jews expelled from Spain and Portugal had a command of many languages, and were well versed in the different branches of trade and commerce. As such, they initiated independent trade connections with colleagues across the Ottoman Empire. In the 16th and 17th centuries, most of the Jewish population of Monastir worked in commerce, brokerage and clothing manufacture – wool trimming, spinning, weaving and leather tanning. They were also goldsmiths, tax collectors, butchers, moneylenders, vine-growers, matchmakers and peddlers. Many of them made a living through trade, and often had to travel from place to place, country to country.

Religious Life

Few cities were as blessed as Monastir for its rabbis, dayanim (religious court judges) and chachamim (wise men).

At the end of the 16th century, a fire broke out in Monastir that destroyed the Jewish houses as well as both the Aragonese and Portuguese Synagogues. As a result, the two communities decided to establish a joint fund in order to rebuild one synagogue – they did not have enough money for both – in which they would all pray, and when finances improved, a Beit Midrash (study hall). In order to decide what would be built first a lot was cast, and the Aragonese synagogue was chosen. The two communities shared the premises for a while, but from time-to-time, frictions arose. As the Beit Midrash that was supposed to be assembled on the Portuguese lot was never built, the Portuguese community asked for help from the Aragonese community to build their own synagogue, but the response was negative. However, the period remained mainly one of calm and reconciliation between the two communities.

In the 17th century, the Jews of Monastir were too populous to be housed in the available synagogues, and non-Muslims were forbidden from building new prayer houses. Thus the community was forced to compromise, and in January 1643 began to rent extra space on a daily basis. The use of private homes for prayer services became customary for many generations.

For further reading on religious life and the rabbis of Monastir >>>