The Janitor's Cellar

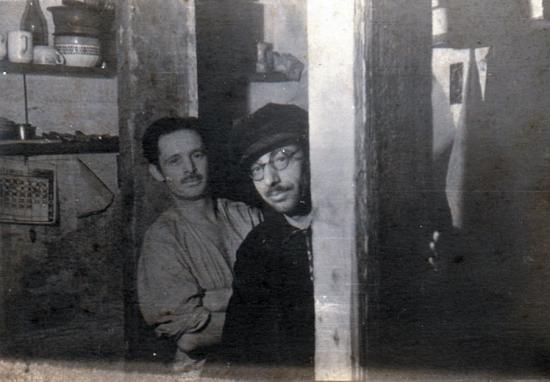

Roberts Sedul, a former seaman and boxer, worked as the janitor of a building in Liepaja. Before the war he was on friendly terms with a Jewish resident of the building, David Zivcon, and had promised to help him in time of need.

After the German occupation, Zivcon was put in the ghetto with the other Jews of the town. He was an expert technician and was therefore employed by the Germans as an electrician. It was during his work, while he was doing repair work in a German apartment, that he came upon photos of the killings of the Liepaja Jews on the seashore. With the help of a photographer friend in the ghetto Zivcon made copies and buried them in the ground.

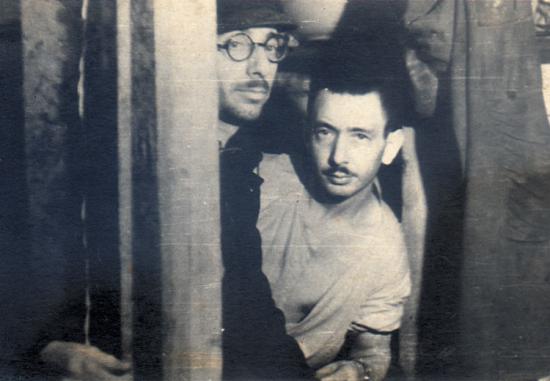

In October 1943 David Zivcon decided that the situation had become too dangerous and that it was time to go into hiding. He fled from the ghetto with his wife. They were joined by another couple, and all four appeared on Sedul’s doorstep. Sedul welcomed his friend and the unannounced guests, and arranged shelter for them behind a concealed partition in the building's cellar. They were to remain there and not to see daylight until liberation 500 days later.

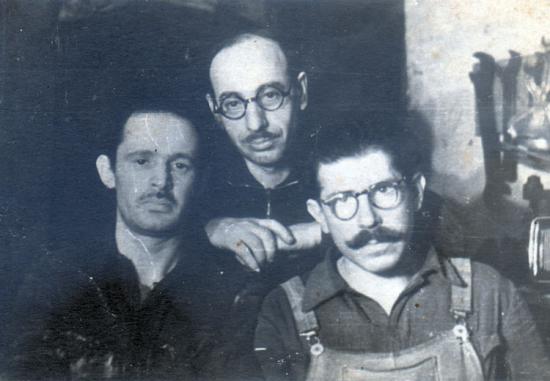

Eventually the hiding Jews were joined in the cellar by another three men. They were jewelers who had been left behind, after the ghetto’s liquidation, to work for the Germans. Sedul had offered them his help, thus bringing the number of Jews in his care to seven. Providing food for so many people in wartime was a great challenge. Since some of the Jews hiding in his cellar were expert workmen, they did different repair work, which enabled Sedul to earn additional money and pay for their food.

In April 1944 Sedul brought another three Jews to the cellar. They had been part of the work detail kept by the Germans for cleaning-up assignments in a military base in the Liepaja area. Aaron Vesterman, described how they knocked on Seduls door and were warmly received by the couple. They were offered food and Sedul gave them a gun and took them down to the cellar where they were surprised to find the other hiding Jews.

A week later Riva, David Zivcon’s sister in law, came along with her three-year-old child, Ada. Her husband had been killed as soon as the Germans had entered Liepaja, on 24 July 1941. Before he went into hiding, his brother, David Zivcon, told Riva that if she ever needed help, she could try Sedul. Probably for the sake of security, he didn’t reveal that he himself was planning to hide with his Latvian acquaintance. Riva, had survived in the Liepaja ghetto with her daughter, and was then sent to the Riga ghetto. She somehow managed to escape before the final liquidation of the ghetto, and returned to Liepaja. All the Jews had by then been killed, but she remembered the name her brother in law had given her, and came to Sedul. He took her in, and when he took her to the cellar to join the others, she was surprised to find David Zivcon.

Fearing that the child would give up their hiding place, Sedul decided that he needed to place here somewhere else. He found a safe shelter for her with Otilija Schimelpfening, a widow of German origin. Schimelpfening changed the child’s name to Gertrude and told her neighbors that the little girl was a relative that had lost her parents. It seems that Sedul did not tell Schimelpfening that the child’s mother was alive, and when the war ended and Riva Zivcon appeared to take her daughter back, it was painful for Otilija Schimelpfening to part from the child she had loved and cared for. As a result the two women did not keep in touch in the years to follow.

Sedul took care not only of the physical well-being of his wards, but also made sure to keep up their spirits. In order to alleviate Riva’s worry about her daughter and the pain of separation, he would visit the child, make sure that she was well taken care of and also took photos of her which he would bring to her mother.

Sedul did not live to see the day of liberation. On March 10, 1945 he was killed by a Russian shell. His wife, Johanna, continued to care for the hiding Jews until the end of the war. After liberation the eleven Jews emerged from the cellar. David Zivcon retrieved the copies of the photos of the massacre of the Liepaja Jews from where he had hidden them. Thus Sedul had saved not only the lives of eleven Jews, but also the evidence about the murder of the entire Jewish community of Liepaja.

In 1981 Yad Vashem conferred the title of Righteous Among the Nations on Robert and Johanna Sedul.

Twenty-five years later, and only after her mother died, Ada Zivcon-Israeli applied to have her rescuer, Otilija Schimelpfening, honored.

From the Diary of Kalman Linkimer:

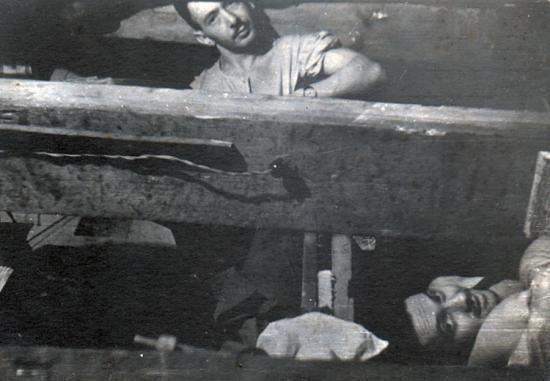

Everything was provided for. Shovels and axes lay ready, in case the cave was buried during a bombing. Also a pantry of food to last for an extended time, in case an emergency prevented Seduls from getting it for us. There is also a water reservoir, electricity, a home-made radio, and a few improvised beds for the women. For the six men, room has been left on the ground to sleep. A small lavatory for women had been installed in an underground passageway. The men relieve themselves in a shovel and throw it into the furnace. The chairs have rubber fastened under them so that they do not make noise. Speaking must be in whispers because upstairs is a bakery, and we must be very careful not to be heard. In short, if no mishap occurs, we can hope to make it out of here. A signal-lamp had also been wired from Seduls’s room to the cellar: one long signal means turn on the motor, a second long signal – turn it off. Two short ones mean that Seduls is being called upstairs. Three short ones – everyone must disappear from the front room because someone is coming into the cellar. Five means that Seduls is coming downstairs. And many signals in succession means – alarm. Then everyone must take out his pistol and stand in readiness. On the walls hang several maps where the position of the [Eastern] front is sketched every day. I saw all this on my first day in the cellar.

Wednesday, 28 June 1944

Robert comes in agitated. The baker from whom he buys bread has confided to Dr.

[Emilija] Cena that Robert is probably feeding pagrīdnieki [underground people, fugitives] because he is buying so much bread every day. He decides not to buy from him anymore, and will be very careful overall when shopping for food. He will share his ration cards with us.

Thursday, 6 July

An appeal by England [is heard on the radio] to the people of Hungary, Czechoslovakia and eastern Germany... Everyone who helps the Jews will be recognized as an ally in the battle against Hitler’s regime.

I tell Robert about the appeal on the radio. He replies:

"I took you on without being asked. I did not wait for you to come to me; I went to find you. I did not seek your money or your belongings. I wanted to save you because David was my good friend, and because I am simply willing to take great risks for such causes. And now I want to say something serious to you. I know that the time of Latvian liberation is approaching. How and what will happen, I do not know. I only know that you will want to take revenge on the murderers, and you have a right, even an obligation, to do this. But I ask of you one thing: that no more innocent [people] suffer. And when an innocent person comes to you, don’t shut the door to him: help him, don’t let yourself become carried away [by blind revenge]; remember that I also helped you only because you are innocent."

Tuesday, 11 July

We hash out the issue of domestic discipline again. I say that some people among us have already lost their nerve too much, and must pull themselves together because [there have been] several clashes from Friday 7th between Riva and Zelke, where Riva completely lost control of herself and raised her voice.

I told Riva: "Calm yourself, for goodness sakes." She shouted back, "You calm yourself!" (The reason: Zelke had entered the hatch when she was ironing.)

Sunday, 12 November 1944

Robert is grim-faced again today. His tone is bossy. When he is in a bad mood, he is dangerous. He yells and makes a racket. When someone tries to calm him down, he yells even more and says, "I want to yell so that the whole house hears! Let the police come on my account! Let it cost me my head and your heads, too."

I had already lost my respect for him for his earlier behavior alone. [Our survival] depends solely on his mood.

On the fronts, no change.

Tuesday, 5 December 1944

Riva has completely lost her nerves. She gets agitated over every little thing and immediately begins to cry to the point that she cannot speak. Yes, the cellar wears upon one’s nerves…

Tuesday, 6 February 1945

Robert is terribly nervous. This whole business [of caring for us] is dragging on too long. If he had known, he would have considered it very carefully. I understand him very well, but how are we to blame?