Following World War I, Hofstätter's family moved from Galicia to Vienna, then to Amsterdam and eventually to Frankfurt. In 1921, the family returned to Vienna, where they settled permanently. Hofstätter worked as a salesman. In 1938, after the Anschluss, the Gestapo arrested his parents. Osias along with his brother and sister managed to escape, to separate destinations. Ben-Zion and Fradl, his parents, were deported to the Lodz ghetto, where they were murdered in June 1942. Osias escaped to Belgium, where he was reunited with his fiancée, Anna Schebestova; they married in Brussels in November 1938. In 1939, due to severe financial difficulties, they moved to the Marneffe refugee camp, established by the local committee for Jewish refugees in Belgium. After Belgium's capitulation in May 1940, Hofstätter was arrested and transported to the St. Cyprien Camp in southern France, and from there to the Gurs Camp.

Thanks to efforts made by his siblings, who had escaped to Switzerland, Hofstätter was released and escaped to Switzerland via the Alps in 1942. He was arrested by the Swiss border police, and transferred to a refugee camp. In 1943, with the help of the Unitarian Service Committee, he was released in order to attend an art school in Zürich.

A year after the end of the war, Hofstätter returned to Vienna, where he was reunited with his wife, and completed his studies at the Academy of Applied Arts. The couple moved to Warsaw in 1948, and immigrated to Israel in 1957. Although he gained recognition relatively late, his works were displayed in numerous exhibitions in Israel and abroad.

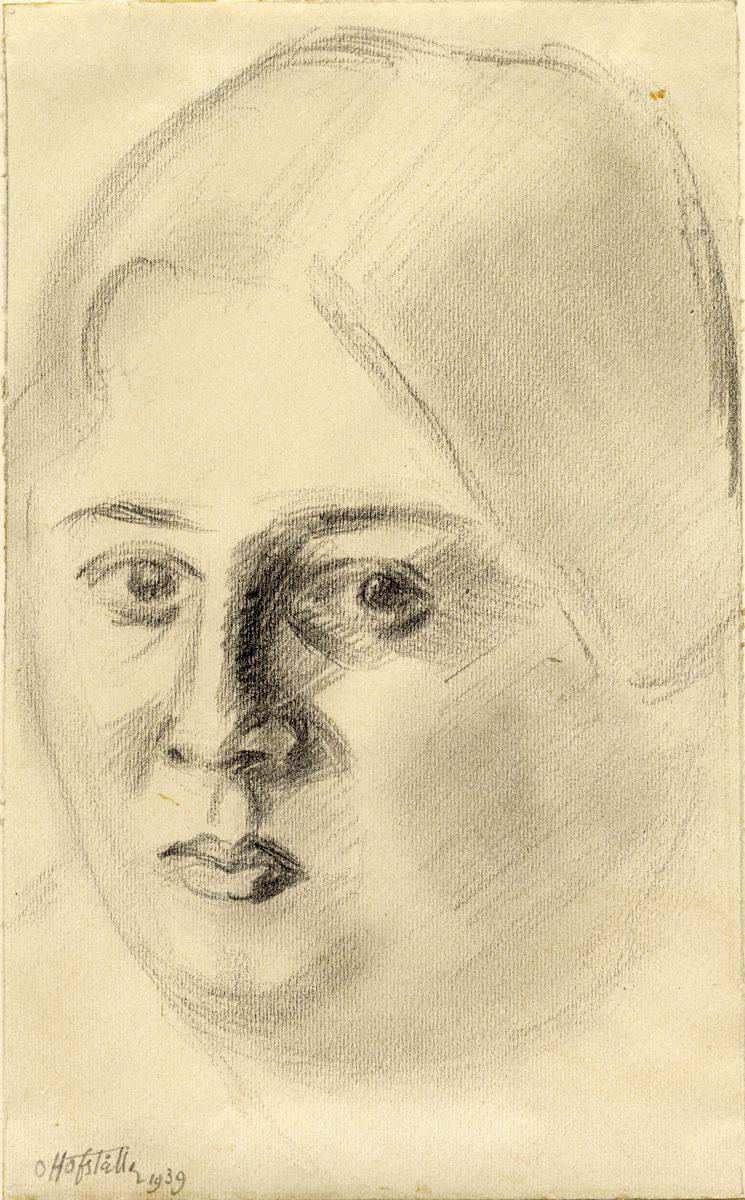

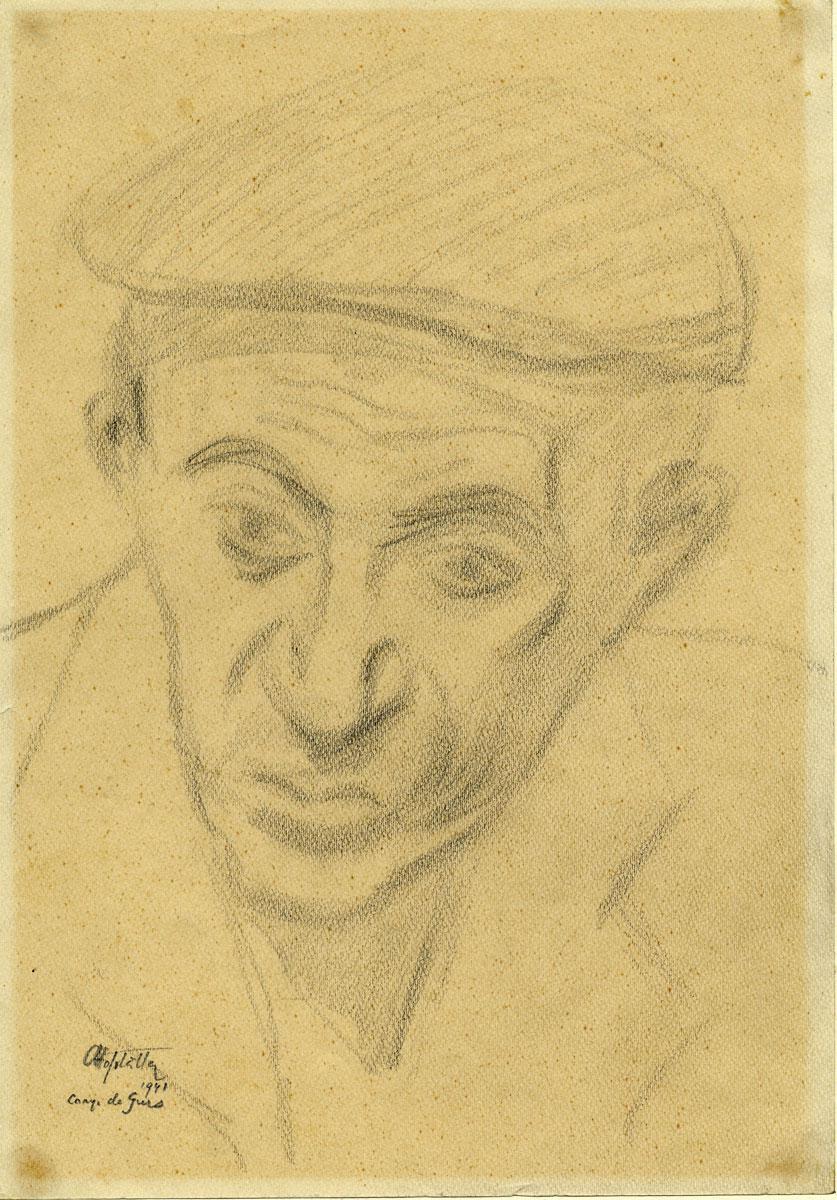

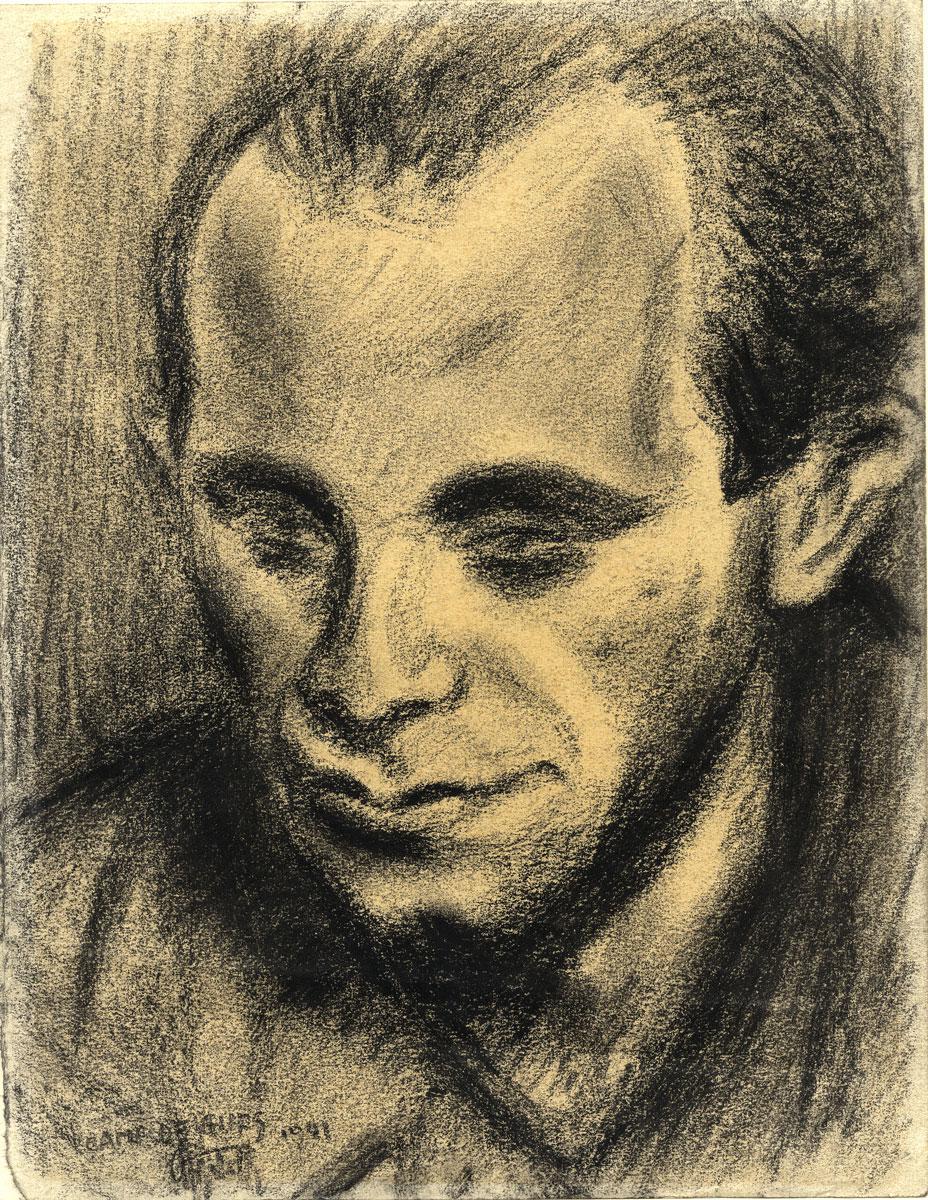

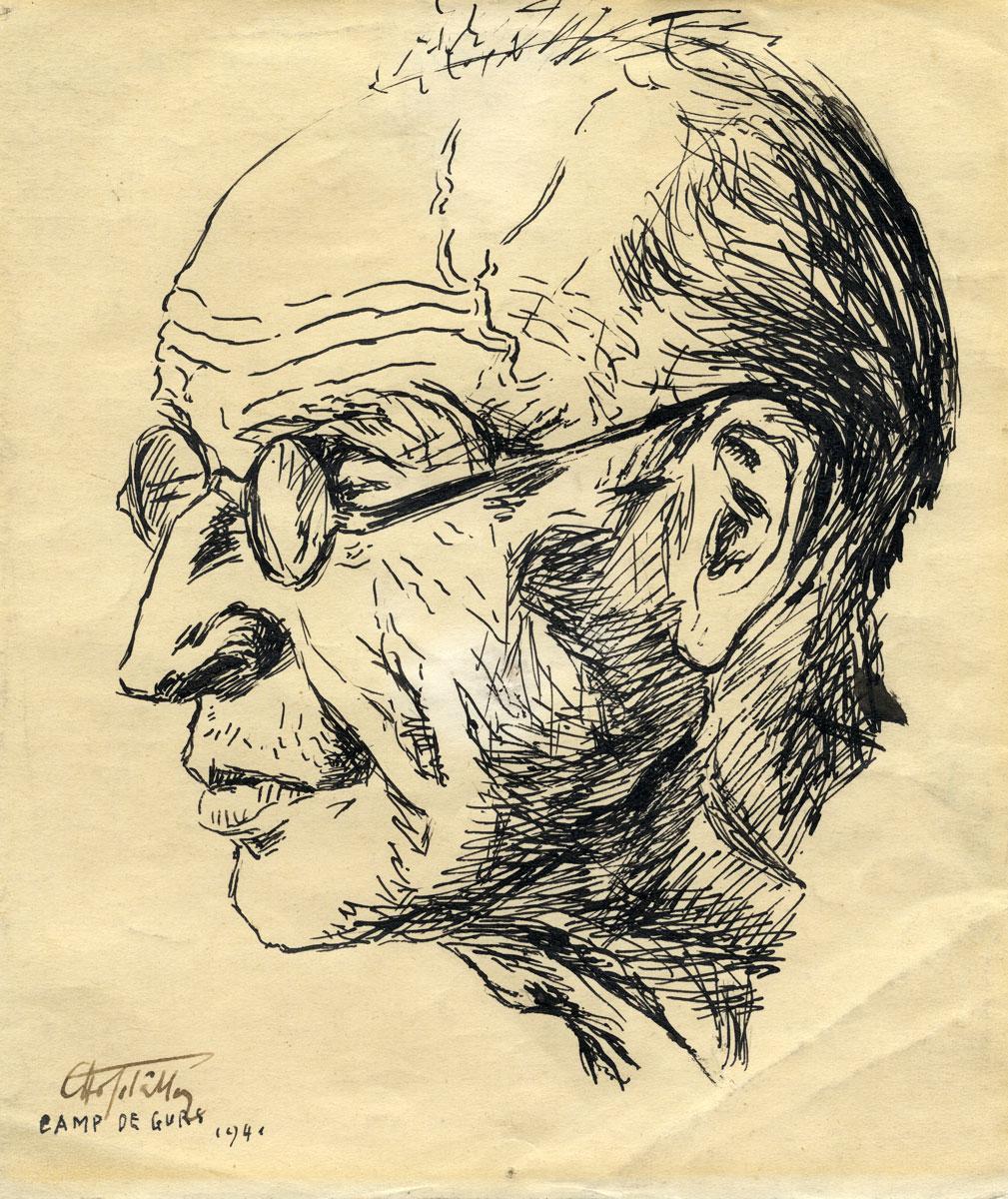

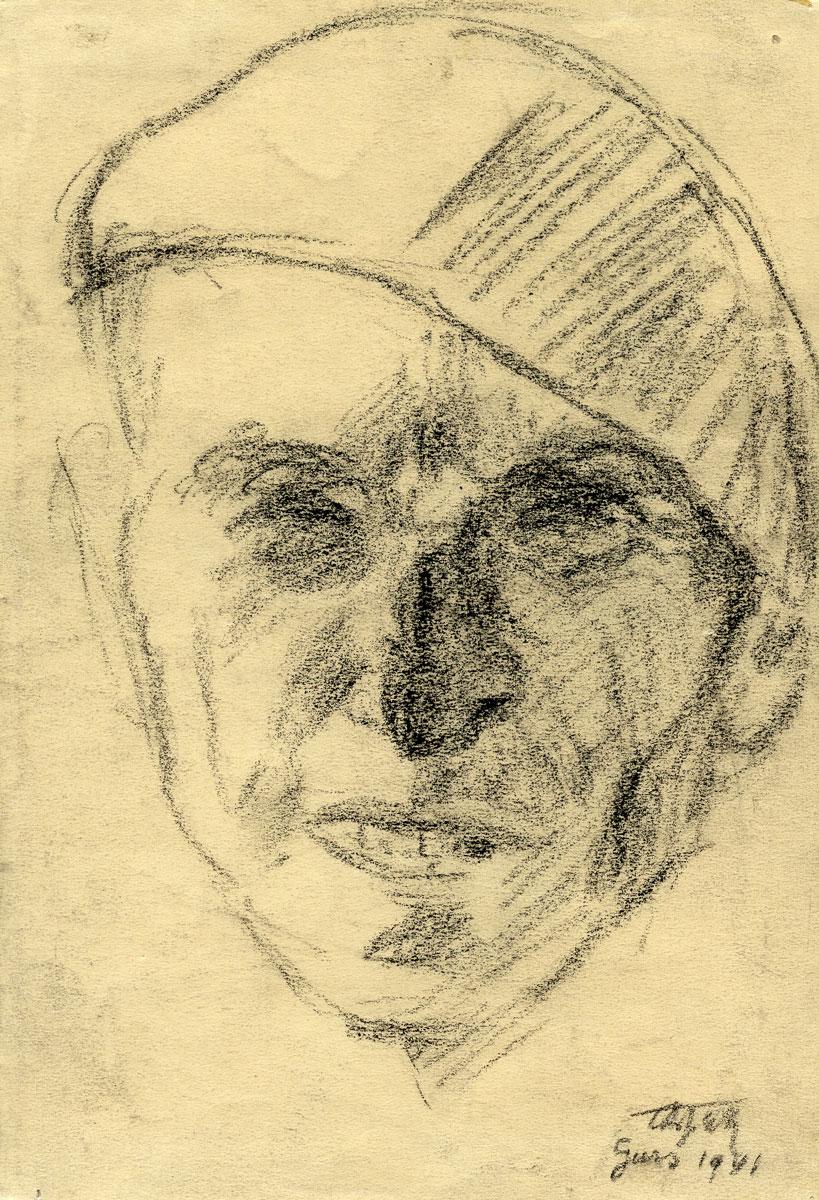

Throughout his incarceration in the various camps, Hofstätter focused on portraiture. While at Gurs, his sister sent him crayons and small sums of money, enabling him to buy art supplies. The portraits on display depict the despair and depression of his fellow inmates. These figurative portraits reflect the initial stage of Hofstätter's artistic career, before he developed his unique expressive style echoing his personal trauma as a survivor of the Holocaust.

In the exhibition “Last Portrait: Painting for Posterity”, Yad Vashem continues in its persistent endeavor to restore a face and a name to the victims of the Holocaust and tell their personal story. Despite our efforts, some portraits remain unidentified. If you have additional information about the portraits and/or artists that are part of this exhibition, please contact the Yad Vashem Art Museum staff.