The Lodz ghetto by all accounts embodied one of the worst cases of human suffering in an enclosed virtual prison for an extended period of time. It was the longest standing ghetto, from 1940 until its final denouement in the autumn of 1944. The fact of its total isolation from the rest of the city multiplied the effect of the near-total lack of all necessities for maintaining life.

Within this reality, we find the human spirit reacting in every possible variant from paralyzing depression to the writing of poetry.

We present in this article two examples of this extraordinary human quality that display the ability to rise above unspeakable circumstances with poems born from this very suffering. Adding to the wonderment of this writer is the youthful ages of the two poets we present below.

- Avremek and his father Mendel passed the initial selection on the train ramp outside Auschwitz and were directed into their new lives as prisoner-slaves within the Auschwitz camp system. Subsisting in the inhuman conditions of an Auschwitz hut which housed several hundred prisoners, Mendel on a particular day wanted to spare his young son another day of back-breaking labor and told him to remain in the hut when the prisoners marched out in their work detail. That was the last he saw of Avremek. On his return in the evening, the father understood that his son had been taken in a sudden S.S. sweep of the huts looking for shirkers. According to the testimony of Mendel’s stepson and Avremek’s half brother Eliezer Greenfelt, Mendel.

- Avramek Koplowicz, Mishe Atzmi, Shirim shel Na'ar m'Ghetto Lodz (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1995), p. 41 (Translated from Hebrew by Jackie Metzger).

- Youth Writing Behind the Walls.

- Avraham Cytryn, Youth Writing Behind the Walls, Avraham Cytryn’s Lodz Notebooks, (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2005), p. 216.

- Avraham Cytryn, Youth Writing Behind the Walls, Avraham Cytryn’s Lodz Notebooks, (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2005), p. 201-202.

Avremek Koplowicz

The younger of the two poets, Avremek Koplowicz, was born in 1930 in the city of Lodz and was able to enjoy the first nine years of his life only. With the outbreak of war and the German invasion of Western Poland, Lodz was overrun and the whole region was incorporated into the Third Reich. Within the first year of the war, the ghetto of Lodz was created and by the end of 1940, the Jewish population of about 180,000 was enclosed within the walls.

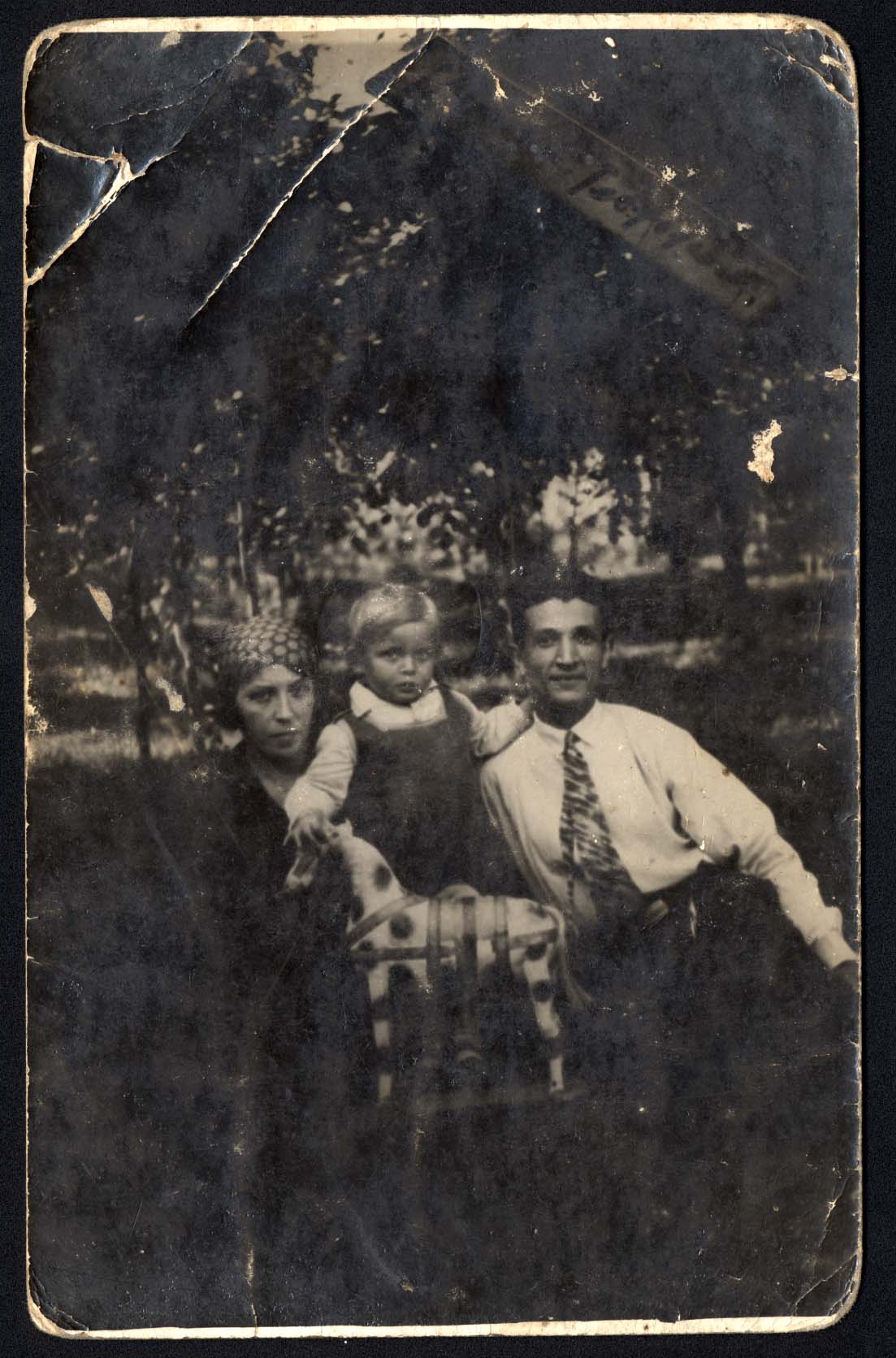

Avremek was in his eleventh year and the next four years with his mother and father in the ghetto effectively ended the happiness of a short childhood. During these years, the boy-poet wrote his poems in an exercise book which remained in the family apartment, untouched, until his father Mendel Koplowicz, the only one of the three to survive Auschwitz, returned to that apartment to find his son’s writings where he had left them on the day they were transported to the death camp.

The father, Mendel, was so traumatized with guilt by the manner of the boy’s death1 in Auschwitz that the poems in his son’s handwriting remained in his drawer unseen and unknown to anyone until his death in 1983 in Israel, to which he had emigrated with his second wife ten years after the war.

The poems were discovered by Mendel’s stepson who rescued them from their anonymity. He passed the exercise book over to Yad Vashem which then published the poems with an introduction from Eliezer Greenfelt, Avremek's half brother.

- 1. 1

The poem below was written in Polish by the young boy Avremek and this copy of the poem in his handwriting, as discovered in the exercise book, provides some sense of how young he was. Yet the content of the poem would seem to indicate the observations of one way beyond his second decade of life.

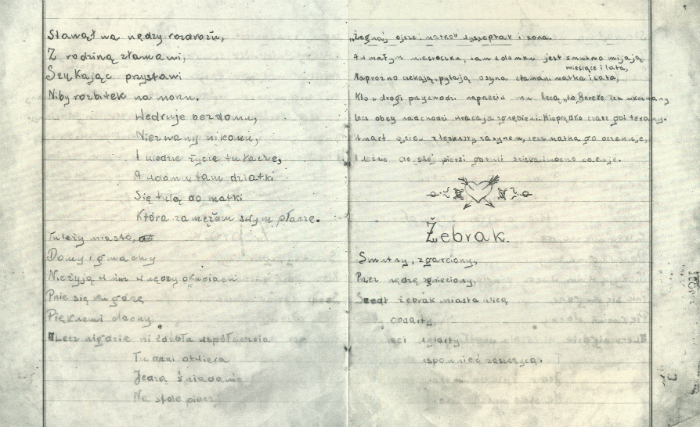

The Beggar2

Sad and hunched over, spent and bent over

He walked the streets (dressed) in his rags

The beggar.

Forgotten by all, at the crossroads of penury

He stopped in his tracks, mumbling from memory

My poor broken family

And I seeking a life-saver

As one gasping in a sinking ship

Just like a homeless wanders the streets

A stranger to all those around him

He lives the life of a nomad.

Back at home the children are crying

Clinging in close to their mother

Yet she is constantly weeping with longing

For her husband out wandering the streets.

Here in the sprawling city

With buildings and apartments

[…]

He opens a door, behold

People eating a breakfast repast

On the table some butter

Together with things from the baker

“Would you spare me a sliver

to enlighten my soul?”

Engaging him now with an ominous glance

Tapping his leg in very evident anger

The man shouted, ”Get out”

Slamming the door in his face.

The beggar retreated, hungry and thirsty

Seeking respite from the wind.

All around him a storm boding the onset of autumn

As his soul he commended to god.

Through a strange gate he will enter

Falling asleep in the shelter.

Aspects of the Poem

The poem highlights several aspects of the suffering prevalent in the ghetto, as seen through the lenses of such a young person.

Avremek speaks of the inequality of suffering within the ghetto.

One would tend to imagine that the suffering in the various ghettos was equally divided, just as descriptions of hardship and deprivation are usually generalized. But in reality, there were people in the ghettos with connections in the right places that enabled them to rise above the harsh conditions for a period of time. (See the article on Henryk Ross in this newsletter.)

Verse three in the poem, beginning with “He opens the door…” plunges the reader from the already depressing descriptions of the beggar in the first two verses, into a charged and unpleasant confrontation between the beggar and a ‘privileged’ family. The humiliation of the beggar as created by the young poet in the reality of the ghetto years ago is made searingly tangible to the reader of today.

- 2. 2

The beggar in the poem represents the majority of the ghetto population. He is wretched and helpless. There is no let-up in the poem and the rambling beggar does not provide any prescription for improvement. The last three lines invoking god and entering a strange gate where the beggar falls asleep could be read as the ultimate stage of succumbing to reality.

Avremek also discusses the fact that human beings behaved differently in the face of such suffering. A population of more than 160,000 people as in the Lodz ghetto would naturally be comprised of all types of people all endeavoring in their own way to survive another day. The magnitude of the Holocaust can lead one to see it more in its macro context at the expense of pursuing the individual narrative. As in the point above which discussed how there were different levels of suffering, on the aspect of human nature, Avremek Koplowicz tellingly paints in words an unpleasant confrontation between the good and the bad, or the feeling and the unfeeling. The reader is brought face to face with unpleasant examples of human nature. The young poet does not flinch from portraying evil within the Jewish circle of suffering.

Avremek's poem also describes the tragedy of disintegrating family life. He lived with his mother and father through the four years of the Lodz ghetto until they were transported together on the last transport in September, 1944 to the finality of Auschwitz. However, during those four years, the young boy must have been witness to countless cases of families breaking up in every conceivable configuration. The last three lines of the first verse state this aspect very clearly.

Avraham Cytryn

The second poet we present here was three years older than Avremek Koplowicz.

Avraham Cytryn was born in 1927 in Lodz and lived through the suffering of the Lodz ghetto from fourteen to seventeen years of age. His father died of starvation in their apartment in November 1942 at the age of forty-two. Avraham, his mother and sister Lucy, were transported on one of the last trains to Auschwitz. Avraham was gassed there on the third day after arrival. His mother also succumbed and only his sister Lucy survived, returning to their apartment in Lodz after liberation and discovering all Avraham’s notebooks with his writings except the one that he had taken with him on the transport.

The drama of the fifty years that separate the writing of the poems in the ghetto and Lucy’s decision to deal with her brother’s legacy is powerfully presented in the book Youth Writing Behind the Walls, Avraham Cytryn’s Lodz Notebooks3, in which the sister, Lucy Cytryn-Bialer contributes the concluding section called Memories. That part of the family story is fascinating in itself but we will limit ourselves to presenting Avraham’s perception of the stark ghetto reality at the time as events were unfolding.

The Cheerful Pessimists4

Dear friends! To hell with sorrow

What does it have to do with youth?

Pessimism is worthless.

Dear friends! Not every day can we laugh.

Off with you, sorrow. Long live joy!

Leap, turn, move!

Throw your pains and bad habits into the

rubbish heap.

We are cheerful pessimists,

Youthful, as light as the wind.

Hurrah to youth, long live joy, and to hell with

All the rest!

Life is fleeting and filled with dangers.

So let us remain united forever.

He who has drained the cup of misery

Will be plagued by fear all his life.

Let joy intoxicate us into forgetfulness

Let us forget our suffering and troubles

Off with you sorrow that stymies our hearts.

From the title of the poem to the last line, the writing is suffused with a false bravado that underlines a feeling of helplessness prevalent in the ghetto perhaps especially amongst the young people. We know that the young Avraham was active in a small literary group that met in the ghetto and that he had very clear ideas of how the group should be run and how the writers and artists could be encouraged to face down the difficult circumstances and channel their creative energies.

The poem above might have this circle in mind but its relevance might also be simply directed at the younger people in the ghetto.

Aspects of the Poem

The first thing that engages the reader's attention is the oxymoron in the title of the poem. The screaming contradiction of "cheerful pessimists" plunges the reader directly into the whirlpool of 'hoping against hope' in the relentless downward spiral of the ghetto. (See the article on the final days of the Lodz Ghetto, in this newsletter).

The tone of the poem belies the difficulties of life in the ghetto. The bellicose, coarse attempt at bravura is clearly hollow of content or true hope. The very marked emphasis on the young people in the ghetto and the unspoken sadness at the loss of youth heightens the discomfort of the reader when he/ she contemplates the young age of the poet, Avraham Cytryn. An overriding negativity pervades the fabric of the lines to the point where it reads even as a eulogy to all that is lost and will be lost…the inevitability of an approaching end.

It should be noted that in both poems presented in this article, there is no mention at all of the German oppressor. The presence of the suffering and the sorrow, the pain and the dangers, the hungry and the thirsty, the weeping and the longing – all words taken from the two poems – in the absence of any mention of the perpetrator responsible for all this, certainly provides food for thought as to the minds of the two young poets, Avremek and Avraham.

I would like to conclude this article with a few lines of prose written by Avraham Cytryn in the ghetto under the title, The War. It is a short piece from which I have taken the first few lines and the last few lines. The contrast between the two quotes stemming from the same pen embodies the depth of the tragedy at the loss of these young people and what they could have achieved.

The War

The ghetto sleeps, cramped in the leaden sleep of the miserable. The nighttime hours are usually the sweetest, because they tear the Jews away from the sorrow and sadness of the reality. But the truth us that even as they lie under their warm blankets, sleeping and snoring, in their dreams they see pictures of horror and catastrophe. The hell of the daily dramas seeps into their nightmares, turning into horrific scenes…A new era will spring from the vestiges of the monstrous hydra, progress will flourish, and there will be no more horror. Humanity lives, humanity creates. From the ruins, a new era will flower and from it will spring culture and progress, beauty and sublimity.5

One would hope that the prayer expressed in the concluding lines be ascendant over the ‘nighttime’ realities described in the first quote.

What is beyond any doubt is the fact that both Avremek Koplowicz and Avraham Cytryn had a wonderful gift with the pen that was not permitted to develop beyond their initial budding.

- 5. 5

![Page from a youth group album produced in the Lodz Ghetto. The Hebrew text reads, "He [who watches over Israel] will neither slumber nor sleep", from Psalm 121:4 Page from a youth group album produced in the Lodz Ghetto. The Hebrew text reads, "He [who watches over Israel] will neither slumber nor sleep", from Psalm 121:4](https://www.yadvashem.org/sites/default/files/1597_29.jpg)