Creating art can be an exhilarating yet painful process for an artist as he grapples with his emotions, his vision, his message, and his limitations. Throughout his artistic life, an artist grows, learns his craft, explores, and matures in a very personal process. However, external factors like war, upheaval, and social change can rob an artist of the ability to freely pursue his inner calling, and cause him to use his art as a vehicle to record and attempt to contextualize the chaos enveloping him.

Felix Nussbaum was such an artist: a German Jew caught in the relentless downward spiral of Nazi persecution, an artist who in the prime of his creative life had to focus on his own survival. In the end, he was murdered by people who saw him only as an object of hatred - a Jew - rather than as an extraordinarily talented human being with a gift to bring beauty into the world.

The way in which Felix Nussbaum viewed himself as a Jew, a German, and an artist is fascinating. Through his artwork, we see a young man who began his artistic journey with an affirmation of his Jewish identity, before embarking on a path of exploration of his own artistic vision. Later, as a hunted exile, he returned yet again to reaffirm this identity.

Nussbaum was born in 1904 in Osnabrueck, Germany, to Philip and Rachel Nussbaum, the second son after his brother, Justus. Theirs was a close-knit, financially comfortable, and patriotic German family, one that epitomized the phrase “Germans of Mosaic faith” - with nationality taking precedence over religion. Felix’s father, Philip Nussbaum, had proudly served his fatherland during World War I as a solider in the Osnabrueck Cavalry. He was to remain a faithful member of its Veteran's Association for almost 35 years. In doing so, he was not alone - 12,000 Jewish soldiers gave their lives fighting for Germany in World War I.

Recognized as a true talent by his doting parents (Phillip Nussbaum himself was a talented amateur artist), Felix Nussbaum was allowed to pursue his art and enroll in art school in Hamburg in 1922. The young artist then went on to study in Berlin, where he received recognition and acclaim by critics and artists alike. This led to a scholarship in 1932 to paint and study in Rome, under the auspices of the Berlin Academy of Arts. He traveled to Rome together with his girlfriend, the Polish Jewish artist, Felka Platek.

When the Nazis came to power in January, 1933, the reach of Nazi culture and policy extended all the way to Rome, and a new type of art – an art that extolled the virtues of the Aryan race – became the only art tolerated in the new Germany. Felix Nussbaum was no longer seen as a young artist on the rise. He was, according to Nazi doctrine, first and foremost a Jew.

Nussbaum and Platek fled Rome in 1933, beginning a life as exiles, first in Italy, and eventually in Belgium. In the summer of 1934, in Rappalo, Italy, he was reunited with his beloved parents, who had left Germany to live in Switzerland. It was to be the last time they ever met. Much to Felix’s despair, his parents decided they could not permanently leave the country they loved so dearly and identified so fully with, and left the safety of Switzerland to return to Germany. However, following the horrors of Kristallnacht on November 9-10, 1938, his parents left Germany once and for all, fleeing to Amsterdam where their eldest son Justus had already settled in 1937.

In 1937, Felka and Felix were married in Belgium. The joys of setting up a conjugal home, however, were not to be theirs. The couple began their married life under a cloud of fear and uncertainty – refugees in a foreign country where their status was shaky and their future, unclear. This "uprooted life," as Felix called it, led him to paint numerous portraits of himself. These were melancholic mirror images, in which he explored his own identity as artist, brother, husband, son, and refugee. His paintings of harbors and rooftop views of his living quarters became motifs for endless waiting, and feelings of entrapment.

With the German occupation of Belgium in 1940, Felix’s fears of discovery became a reality. He was arrested, thrown into the internment camp of Saint Cyprian in southern France, along with other aliens. In this terrible place, built on the burning hot Mediterranean sands, many inmates succumbed to disease and exposure. It was here that Nussbaum began to fully understand that, as a Jew, his life – and the lives of the entire Jewish People – were now under existential threat. It was a shattering revelation for him. After applying as a German to be sent back to Germany, Nussbaum managed to escape while en route, and eventually was reunited with Felka in Brussels. There the two were forced into hiding, relying on the goodness of friends to shelter them from discovery, and to supply Nussbaum with art supplies. From this point, Nussbaum's artwork began to express his overwhelming feelings of dread, melancholy, persecution, and the approach of death, although occasionally portraying symbols of a fragile optimism.

This optimism was not to be realized. In July, 1944, Felka Platek and Felix Nussbaum were arrested, sent to Mechelen transit camp and then to Auschwitz, where they were both murdered. Everyone in Felix's immediate family experienced this horrible fate. His parents, niece, and sister-in-law were all murdered at Auschwitz, while his brother succumbed to exhaustion in Stuthoff. The only crime they had committed against the country of which they were once proud citizens was that they were born Jewish.

The body of work Nussbaum left behind in his brief 40-year life is extensive. In these paintings one can trace the painful journey Nussbaum made from a proud young Jewish man, aged 21, to the terrified, persecuted victim he became in his thirties.

In 1926, 21-year-old Nussbaum created the painting the “The Two Jews (Interior of Osnabruek Synagogue.)” The viewer gazes into the neo-Romanesque interior of the synagogue of Osnabruek, (built in 1906) with its high ceilings and fine chandelier, towering Aron HaKodesh (Holy Ark), and mixture of both orthodox and assimilated worshippers, identifiable by their different modes of dress.

The central aisle leading into the synagogue is blocked by two figures. The elderly man on the left is a likeness of cantor Elias Abraham Gittlesohn (Felix painted him from life). He doesn’t engage the viewer visually, but rather gazes off to the right, seemingly lost in prayer. Indeed, he seems to be about to slip out of the left corner of the canvas and out of the scene. The young Nussbaum is spatially placed behind the cantor, and yet towers above him. His self-portrait is a truly commanding presence. His tallit (prayer shawl) covers his head and shoulders. He stands sternly, almost defiantly, and locks the eyes of the viewer into his intense gaze, almost as if challenging him.

In 1926, Osnabruek, a provincial town in lower Saxony, had a population of 93,000 residents. Of that number, about 454 people were Jewish – a mere half percent of the population. The Jews of Osnabruek were comfortably middle class and mainly involved in business. The largest majority of Jewish households at the time were elderly, with over 57 households consisting of only one person. It was this older generation – that of Nussbaum’s parents and grandparents – that wanted to embrace the opportunities of equality, and assimilate fully into German life. They gave a nodding acknowledgment to their Jewish cultural identity, doing no more than attending synagogue on the major holidays, and paying taxes to the Jewish community.

In “The Two Jews (Interior of Osnabruek Synagogue)” the youthful Nussbaum shows us a generational conflict between the traditional and the modern. The elderly bearded figure to the left represents the older, more orthodox generation, while the beardless Nussbaum himself is the beneficiary of the opportunities of assimilation. It is Nussbaum’s gaze, as he challenges his viewer, which is so intriguing. Indeed, no matter where the viewer’s eyes wander to in this painting, they always come back to those piercing eyes.

What does Nussbaum’s proud and defiant stance mean? Is he saying to his Jewish viewers, “I am proud to be a Jew, and even as I take my place as an equal in German society, I will not forsake my Jewish culture and identity”? Or, in the increasingly antisemitic atmosphere of Osnabruek in the 1920s, is this defiance aimed toward those non-Jews who would disparage Nussbaum because of his religion?

A self-portrait is a mirror image in which an artist can engage in a dialogue with himself. Perhaps Nussbaum looked into the eyes of his own painted reflection and reminded himself that at his core he was a Jew.

Nussbaum did not return to this depiction of himself as a Jew until circumstances forced him to again re-examine the meaning of his own Jewish identity. This happened in 1941, when in hiding after his escape from the internment camp of Saint Cyprien, he created a series of paintings depicting the suffering he experienced as a prisoner there.

Saint Cyprien, in southeastern France, was first a detention camp for Spanish refugees in 1939 who arrived over the border. When Belgium was invaded by the Nazis in May, 1940, refugees from the “Reich” lands, regarded as “fifth columnists” or Nazi sympathizers, were arrested and interned in the camp as well. Ironically, Nussbaum was one of about 7,500 Jewish refugees sent to Saint Cyprien who had fled persecution from Germany, the very state they were accused of aiding. Built on inhospitable sands, the conditions at Saint Cyprien were appalling – lack of shelter from the sweltering Mediterranean sun, terrible sanitary conditions, tainted insufficient water, and the omnipresent plague of disease. The young artist who, in 1926 had a choice to follow the road of assimilation, now found that his Jewishness was absolute and irrefutable in the eyes of his persecutors. Being Jewish forced him into exile from his homeland and eventually brought him to the burning sands of Saint Cyprien. To be a Jew was now tantamount to a death sentence.

He explored this altered Jewish identify in his painting “Camp Synagogue at Saint Cyprien.” The first impression the viewer gets from the painting is one of darkness and despair – a dark grey sky, its sun obscured by a black cloud and a few desultory flying birds, lowers over a dull brown terrain strewn with the debris from the camp. Standing in the center of the canvas is a black menacing hut, the corrugated tin sheets thrown haphazardly on its roof attesting to the rudimentary and insufficient housing in the camp. Facing this building, which almost threatens to swallow them up into its darkness, a group of four figures huddles. Wrapped in tallitot, (which intentionally or unintentionally are painted an exaggerated length, making them almost shroud-like) and seemingly lost in prayer, they present a united group. Standing apart from them is a lone figure, most likely Nussbaum himself. Like “Two Jews” painted in 1926, he is again wrapped in his tallit, but here the similarities stop. There is no proud eye contact with the viewer in this portrait. Here Nussbaum has his back towards us, and the hunch of his shoulders seems more tense and defeatist than those of the united group on the left who can take comfort in prayer. The viewer cannot tell if Nussbaum is actually praying, or just using the tallit as an encompassing flag, a symbol to show that he still belongs to group to his left, even if spiritually he cannot join in their unshakable piety. This Nussbaum is a diminished man, subservient to the evil powers which threaten to engulf not only himself, but also the Jewish people.

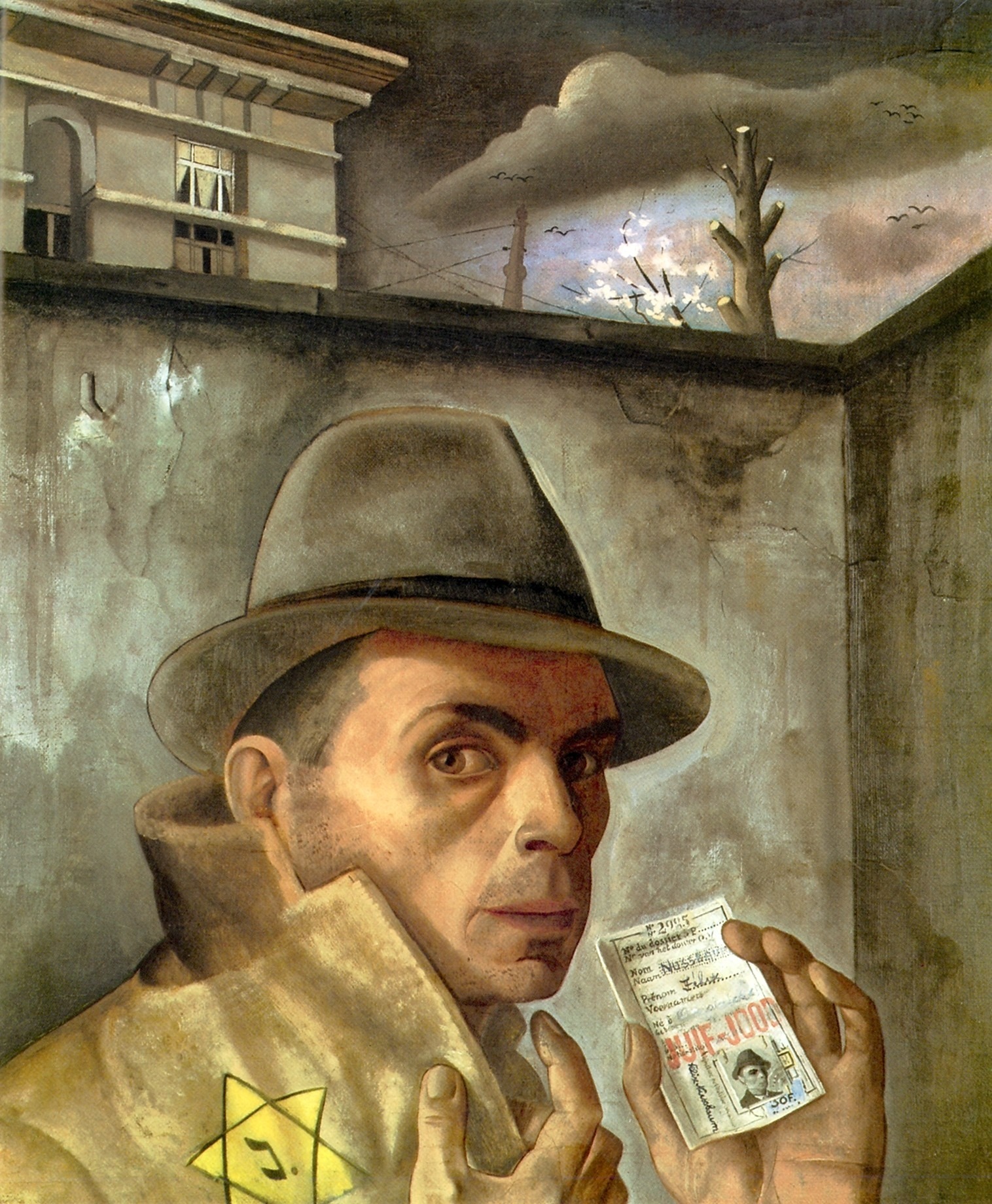

In 1943, little more than a year before his murder in Auschwitz, Nussbaum painted one of his most striking and devastating self-portraits titled “Self Portrait with Jewish Identity Card.” Unlike the first two portraits discussed here, in this portrait, the symbols of Jewish identity do not come from the Jewish faith itself, but rather are symbols of persecution and degradation imposed upon Jews by the Nazis.

Turning his head to visually engage the viewer, Nussbaum seems to have been cornered next to a crumbling and dirty white wall (a symbol of menace in Nussbaum’s visual vocabulary). Lifting his coat collar up, he reveals the yellow badge of shame concealed under it, while his left hand shows us his Jewish identity card. His expression is furtive, alert, his direct gaze is penetrating. What does it mean to us as viewers? Is it a conspiratorial gaze, asking us to help keep the secret of his Jewish identity? Is it the gaze of the accuser, demanding from the viewer answers as to why he has been allowed to be so humiliated and persecuted? Is this the terrified face his persecutors will see when he is eventually arrested in July, 1944? Or perhaps, 17 years after first painting himself as a Jew, he again asks the viewer to consider the implications of what it means to be a Jew at this point in history, with the threat of annihilation looming so close.

Beyond the wall, a dark cloud floats in the lowering dark sky, while windows of a nearby house witness the scene. Do these windows represent the life-saving shelter of hiding, now lost? Perhaps they symbolize the bystanders, those who detachedly witness Nussbaum’s revelation from the safety of their own homes? The tree, which juts up on the other side of the wall, combines two symbols that appear repeatedly in Nussbaum’s artwork. The most prominent part of the tree is limbless; a symbol in Jewish funerary art of a life cut short, and in Nussbaum’s art, a symbol of melancholy, hopelessness and death. In the midst of this dark and despairing scene with a portent of approaching doom, a blossoming branch grows from a lower limb of the dead tree, highlighted by a small patch of blue sky behind it. This small symbol of optimism represents the quintessentially human quality of hope. Even in the shadow of death, most people are loath to believe they will actually die. In the midst of his horrible predicament, it appears that Nussbaum still held on to a glimmer of hope that he and his loved ones would somehow survive.

Felix Nussbaum was one of six million Jews murdered during the Holocaust for merely being a Jew. His genius, his vision, his voice were all snuffed out by those whose hatred prevented them from seeing Nussbaum as a human being. Until the bitter end, Nussbaum created his art, using his talent to visually portray his inner struggles with fear and solitude as an artist, a man, and a Jew spiraling toward catastrophe. Even under such horrific circumstances, in his brief 40 years of life, he still managed to bring great beauty to the world.

By seeing Felix Nussbaum’s artwork, and trying to understand its messages, we honor one of his last wishes: that after his death, his artwork would not die with him.

Sources and Select Bibliography

- Eva Berger, Inge Jaehner, Peter Junk, Karl Georg Kaster, Manfred Meinz, Wendelin Zimmer, Felix Nussbaum: Art Defamed, Art In Exile, Art In Resistance: A Biography, Overlook, USA, 1997.

- Panikos Panayi, Victims, Perpetrators and Bystanders in a German Town: The Jews of Osnabrück Before, During and After the Third Reich, European History Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 4, (2003), p. 451-492.

- Barbara Pfeffer, Art and Remembrance – The Legacy of Felix Nussbaum, Germany, 1993.

- Dali Hakker-Orion, "Felix Nussbaum – the Impact of Persecution on the Art of a German Jewish Refugee in Belgium," in Belgium and the Holocaust, Dan Michman, ed., Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1998.