Children's Homes for Holocaust Survivors

"My Lost Childhood"

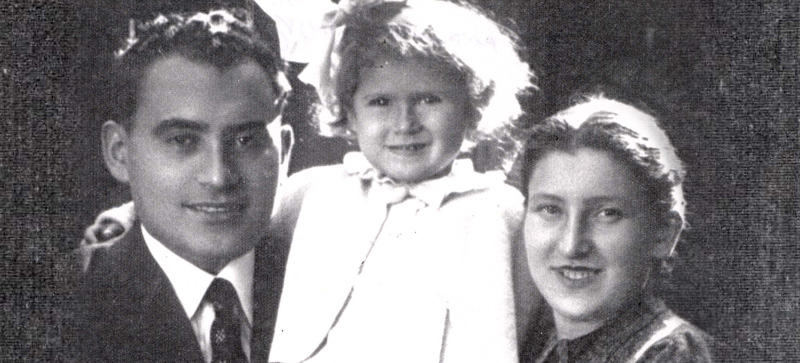

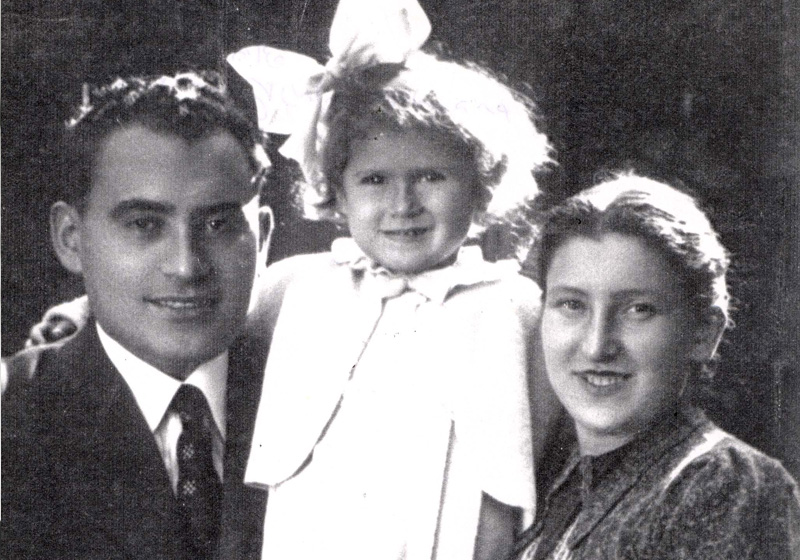

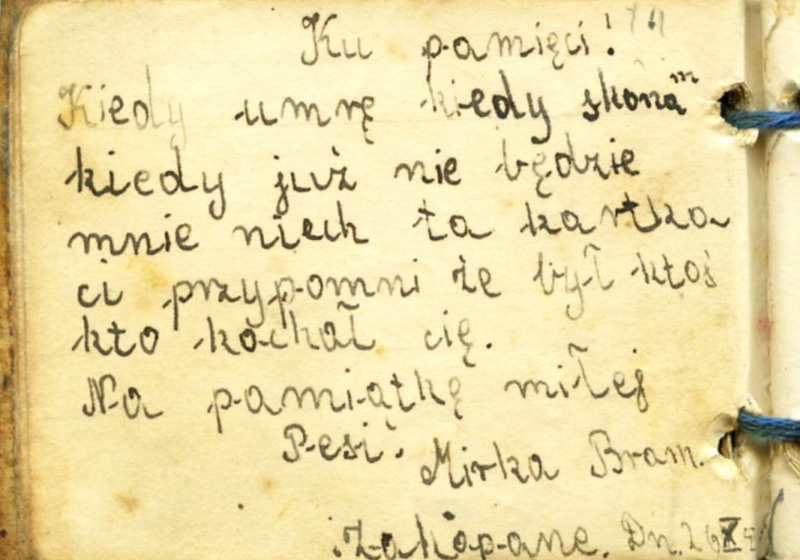

Mirka Bram (Mira Erlich): A Young Girl at the Rabka and Zakopane Children's Homes

On 4 September 1939, the Germans occupied Kalisz, and by the end of the year most of the city's Jews had been sent eastward. Baruch, Lili and Mirka, together with other relatives were amongst those deported to Włodawa, in the Lublin District. All their property was left behind. In January 1941, the Jews of Włodawa were confined in a ghetto. After a time, Baruch and Lili were transferred to a labor camp established outside the ghetto, and Mirka was left alone. The commander of the camp, Bernhard Falkenberg (later recognized as Righteous Among the Nations), acted fairly towards his workers, and always warned them about impending Aktions. In May 1942, an Aktion took place in the ghetto, in the course of which some 1,300 of the ghetto's Jews were sent to the adjacent Sobibor extermination camp. Lili managed to escape, make her way into the ghetto and bring Mirka back with her to the camp. Mirka lived in a barracks with her parents and aunt Surcia. She was alone during the day, and was warned by her parents that she should hide inside the stove if she heard steps approaching.

The Włodawa camp was liquidated in late April 1943. During the liquidation Aktion, Baruch hid Mirka, Lili and Surcia in the barracks and boarded up the entrance with some planks. Baruch himself was caught. That was the last time Mirka ever saw her father. The women emerged from their hiding place and escaped from the camp. They reached the farm where Falkenberg lived, and he agreed to take them in. Someone told the Gestapo that Falkenberg was sheltering Jews and helping local partisans. He denied all knowledge of these charges, but was arrested.

Lili, Surcia and Mirka escaped from the farm to the nearby forest. Lili and Surcia brought Mirka to a family of farmers in the adjacent village of Adampol, promising them to reward them after the war with gold hidden in Kalisz. Several days after Mirka was brought to the village, the Jews who had escaped from the camp were caught and murdered, amongst them Lili and Surcia. The family sheltering Mirka was afraid to keep the child, and took her to the neighboring village, Wyryki, requesting that the head of the village look after her. He sent her with a wagon driver to the Włodawa Town Hall so that Mirka could be assigned papers certifying that she was Polish. The Town Hall offices were closed, and the wagon driver abandoned her. Eight-year-old Mirka was left alone, and returned to the Polish family in Adampol. The next morning, the farmer's wife took her back to Włodawa, and told her to go to the church and ask the priest for help, warning her that if she returned to Adampol, they would turn her over to the Germans. The priest sent Mirka to Dr. Orzechowski, a Polish doctor who knew Mirka and decided to help her.

The doctor and his wife arranged a cover story for Mirka, telling her that from then on, she was a Catholic by the name of Marysia Marinowska, born in Modlin, an only child whose mother had died of typhus and whose father was a Polish officer who had been taken captive by the Germans.

The doctor's wife brought Mirka to the city of Chelm, and entrusted her to the local Red Cross. In Chelm, Mirka-Marysia met the Preidel family, ethnic Germans, who decided to take her in. Knowing nothing about her Jewish identity, they registered her in the local school. The headmistress suspected Mirka of being Jewish from the very first day. She returned home to the Preidels, and announced that she didn't want to go to school because the other children were bullying her. The Preidel's daughter, Helena took Mirka to her house in Krsanistaw, where she spent the summer months, after which she returned to Chelm. With the approach of the front in 1944, the Preidels left, fearing Russian animosity due to their being Volksdeutsch (ethnic German). They took Mirka with them to Krakow, and put her in a convent while they looked for a place to live, after which they planned to pick her up. One day, the nuns took the children out, stopping to eat at a restaurant in Nowe Brzesko. The restaurant owners' daughter asked Mirka if she would like to stay there, and Mirka agreed, living there until they were liberated by the Russians. After liberation, she revealed her Jewish identity to them. The family made contact with a Jewish family in the town, and one day, a woman came and took Mirka to the Jewish community building in Krakow. There, she found out that two of her father's sisters had survived Auschwitz. Mirka caught pneumonia and was sent to the children's home in Rabka, and from there to Lena Küchler's children's home in Zakopane, where she recuperated. After a while, one of her father's sisters came and took her to Ostrowitz.

Mirka knew that two of her father's brothers and one of her mother's sisters were living in Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine). Having no doubts about her identity, she wanted to immigrate there. She left Ostrowitz for London, reaching the hostel run by Rabbi Dr. Schonfeld of Agudat Israel. In 1947, she immigrated to Eretz Israel and settled in Kibbutz Givat Brenner. There, she was informed that her father had been murdered at Majdanek.

In her testimony, Mira Ehrlich (Mirka Bram) relates:

I came to Eretz Israel with a little siddur (prayer book). The same way I had been with Polish prayers and the Polish [prayer] book, so I was with my little siddur. I thought that everyone here was very religious, and constantly praying - that was obvious to me. My uncle came, and I remember seeing him at the port. He was dressed the way they were then, with short pants and no hat, and suddenly, [I realized that] not everyone was religious. I adjusted very quickly. The same way as I adapted to everything else, I reconciled myself to [the idea of] not being religious. In other words, nothing was ingrained, we adapted very easily.