Read More...

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 4613/413

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 1817

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 1729

In the second row, second from the right, is Theodor Klein

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 4613/329

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 4613/1105

;Third from the left is Into Shymshi, submitter of the photograph, and in the front of the photograph, wearing a uniform and a hat, is David Matzista, a Jewish kapo.

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 5535/3

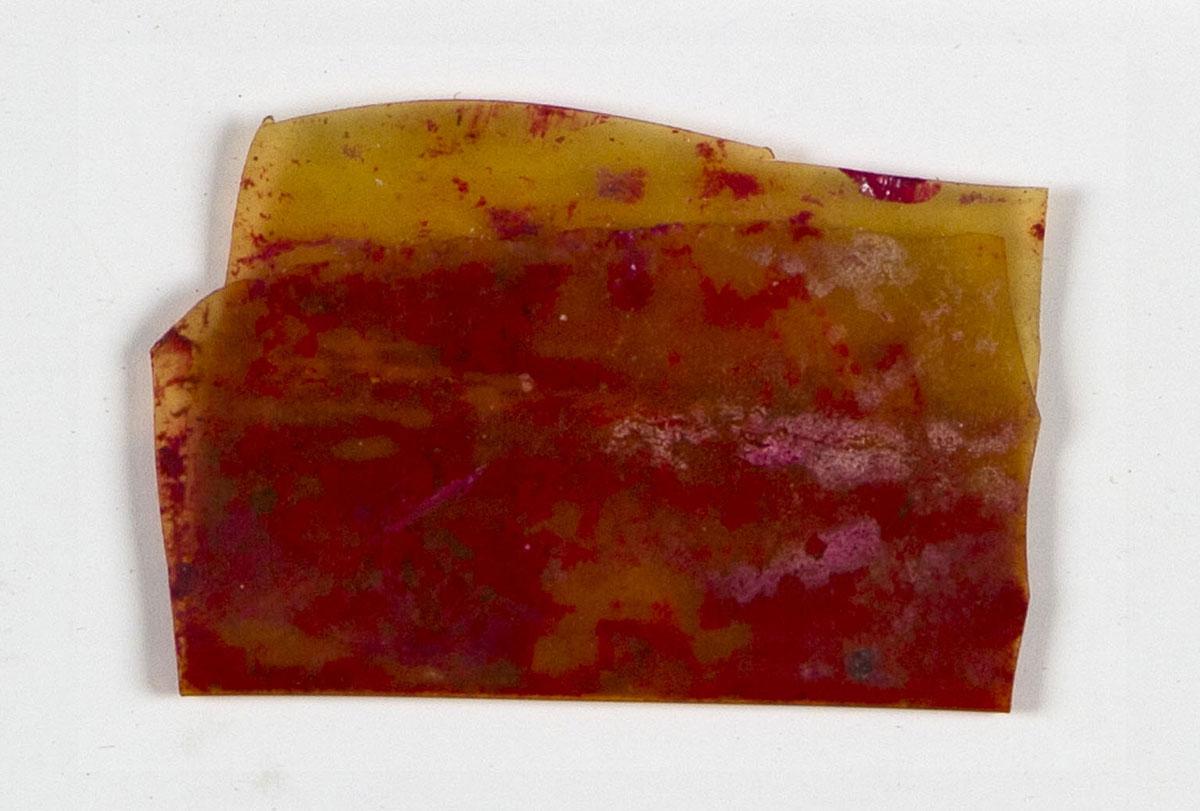

The rouge was preserved in a folded piece of celluloid paper that they kept hidden. They would dab a little on their cheeks before each selection.The two women were forced on a death march, survived and were liberated by the Red Army.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Donated by The Association of Krakovians in Israel

The Shofar was made in anticipation of Rosh Hashanah 5704 (1943) by Moshe (Ben-Dov) Winterter from the city of Piotrkow, Poland, who was an inmate in the camp and worked in the metal workshop of the armaments factory. The idea of making a Shofar was initiated by the Radoszyce Rabbi, Rabbi Yitzhak Finkler, who was a prisoner in the camp. He believed that the inmates must carry out the commandment to blow the Shofar, and thus awaken God's mercy, especially at this fateful time. In spite of the great danger, Moshe Winterter made the Shofar and brought it to the Rabbi on the eve of the holiday. Word spread and the inmates gathered together for prayers and to hear the sounds of the Shofar.

Yad Vashem Collection, Jerusalem, Israel

Donated by Moshe (Winterter) Ben-Dov, Bnei Brak, Israel

Victor Webb, a British soldier who was one of the liberators of the camp, took the whip.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Donated by Bruce Webb, England

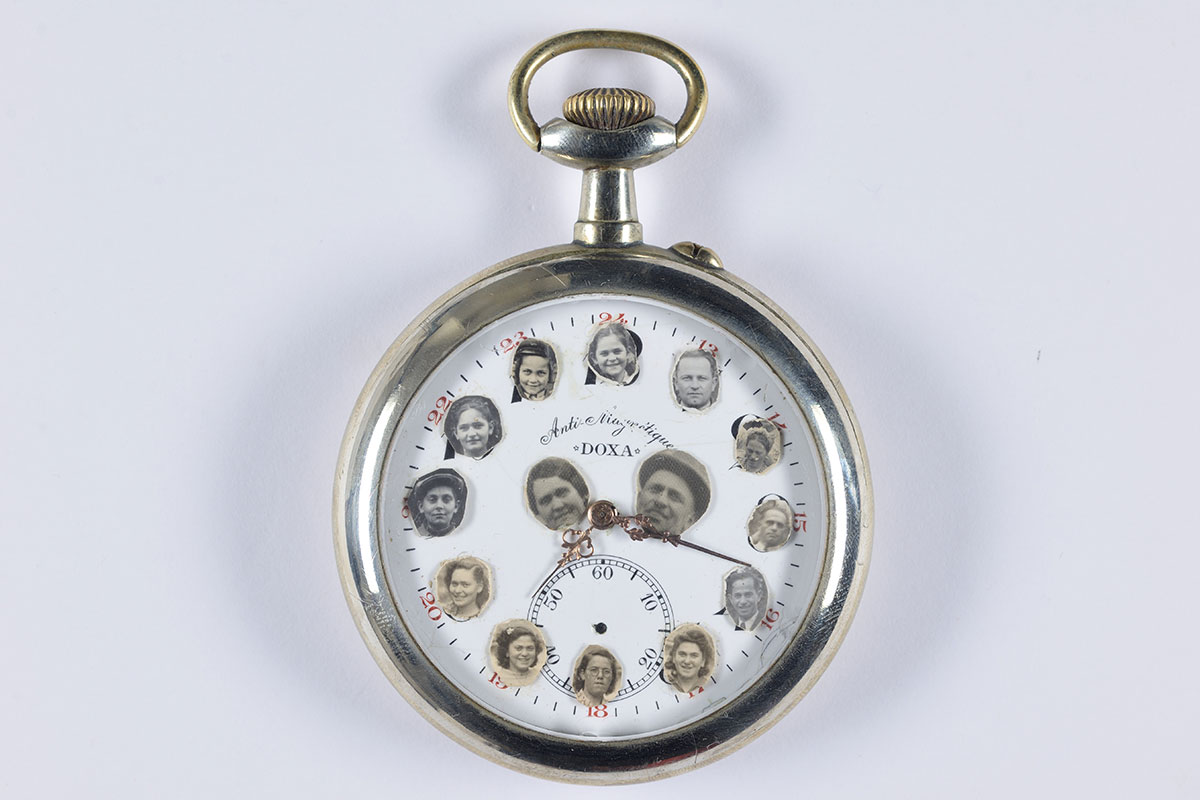

In the center are photographs of Yeshayahu and Esther, and the twelve children’s photos are pasted around the face of the watch in order of birth.On the eve of the family’s deportation, he entrusted the watch to a Christian friend. Isaiah and his wife Esther, along with four of their children and four grandchildren, were murdered immediately upon their arrival in Auschwitz.

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

Gift of Mr. Serge Klarsfeld, Paris, and Mr. Alexandre Oler, Nice

Gift of Mary Simenhoff, South Africa

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

Gift of the artist

Gift of C. Landmann, Zurich

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum

The hierarchic structure of the concentration camps followed the model established in Dachau. The German staff was headed by the Lagerkommandant (camp commander) and a team of subordinates, comprised mostly of junior officers. One of them commanded the prisoners’ camp, usually after being specially trained for this duty. Male and female guards and wardens of various kinds were subordinate to the command staff.

The prisoners had a hierarchy of their own. Prisoner-supervisors (kapos) were considered an elite that could wield power. The prisoners had different opinions about them: most Jewish supervisors tried to treat their brethren well; some were harsh towards the other inmates.

The appel, the daily lineup that took place every morning after wakeup and each evening after returning from labor, was one of the horrific aspects of the prisoners’ lives in the camps. They were forced to stand completely still, often for hours at a time, exposed to the elements in the cold, rain, or snow and to the terror of sudden violence by SS men, guards or kapos. The camp routine was composed of a long list of orders and instructions, usually given to all but sometimes aimed at individual prisoners, the majority of which were familiar yet some came unexpected. All of one’s strength had to be enlisted to overcome the daily routine: an early wakeup, arranging the bed’s straw, the lineup, marching to labor, forced labor, the waiting period for the meager daily meal, usually consisting of a watery vegetable soup and half a piece of bread which was insufficient for people working at hard labor, the return to the camp, and another lineup, before retiring to the barracks.

Despite their terrible conditions, cultural and religious activity continued in the ghettos, labor camps, and even concentration camps. Literary and artistic works that survived the war reflect the Jews’ lives, agonies and efforts to maintain their human and Jewish identity. These works are direct and authentic testimonies and depict the Jewish victims’ daily life during the Holocaust. Writing a diary on scraps of paper, producing drawings and illustrations of camp life, making jewelry out of copper wire, writing a Passover Haggadah, and conducting prayer services on the eve of Rosh Hashanah are all manifestations of the tremendous psychological strength maintained by these frail, starving people. Even at the end of the grueling days they had to endure, they refused to abandon their creative endeavors. Prisoners in concentration and labor camps exhibited heroism and resourcefulness in their daily lives, struggling to sustain not only the ember of physical life but also, and primarily, their humanity and basic moral values, friendship and concern for others – values that facilitated their survival.