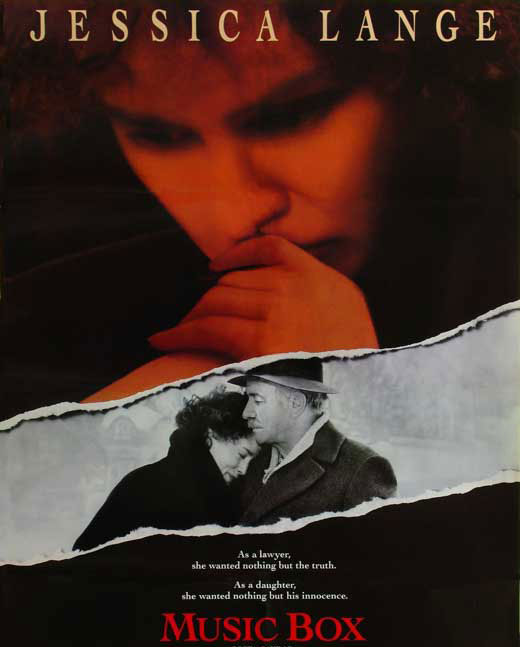

Music Box - Movie Poster

- Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, Penguin Classics, 2006.

- Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Schocken Books, New York, 2004.

Sunday to Thursday: 09:00-17:00

Fridays and Holiday eves: 09:00-14:00

Yad Vashem is closed on Saturdays and all Jewish Holidays.

Entrance to the Holocaust History Museum is not permitted for children under the age of 10. Babies in strollers or carriers will not be permitted to enter.

Music Box - Movie Poster

"Music Box"

Costa Gavras

USA, 1989 / English and Hungarian / 194 minutes

Music Box, released in 1989, was directed by the French-Greek director Costa-Gavras. Joe Eszterhas, who wrote the script, was born in Hungary in 1944. His father Istvan, a newspaper editor, collaborated with the pro-Nazi Hungarian regime and wrote antisemitic literature.

Music Box was produced against the background of the unfolding trial of John Demjanjuk in Israel, and the film bears some striking similarities to it. As we shall see, questions arising from the film are relevant to discussion on postwar court cases against war criminals.

The film focuses on an American family of Hungarian descent: the father of the family Mike Laszlo, his daughter Ann Talbot, her son Mikey and her brother Karchy Laszlo. The idyllic American family picture is undermined when the criminal nature of this father’s past is uncovered.

Mike Laszlo was born in Hungary and has lived in the United States for many years. He is a devoted family man and has a fine relationship with his children and other members of his family. On the surface, it appears that Mike lives a normal, happy life. He seems to be liked within the community in which he is active. His daughter Ann is a lawyer, and her brother Karchy is a Vietnam War veteran.

The story begins with the attempted cancellation of Mike Laszlo’s citizenship by the relevant American authorities because of a false declaration previously made on his U.S. immigration forms. According to the authorities, Laszlo lied on his application forms because during the Holocaust period he had served in a special unit of the Hungarian Nazi gendarmerie – a policing organization that operated in collaboration with the Nazis – and committed war crimes.

Upon receiving the indictment, Laszlo firmly denies it. He states: “I worked in a factory, I brought up children... this is my country and I have lived here for thirty-seven years.” It should be noted that the unfolding of events at this stage is very similar to the beginning of the John Demjanjuk case. There, the court in the State of Ohio demanded the revocation of Demjanjuk’s citizenship for virtually the same reasons.

At this point, Laszlo’s family has to take a stand in light of the accusations leveled against him. The family reacts with total disbelief. Laszlo’s daughter Ann, a lawyer, accompanies him to the initial legal proceedings with the clear understanding that the accusations are based on a mistaken identity. After initial hesitations connected with her direct familial involvement and lack of legal experience in such cases, Ann succumbs to her father’s pleas that she become his defense lawyer and legal counsel.

As a result, Ann’s confrontation with the past becomes a very intimate experience which forces her to grapple not only with the legal aspects of the trial, but also with the love for her father and the close relationship she has with him. This conflict, manifest in her being both her father’s legal counsel and his loving daughter, is a central theme of the plot.

In this way, the film introduces us to the second generation of the murderers, and in this case, to two grown children who had been unaware of their parents’ actions. These American children of European immigrants saw their parents as models of exemplary behavior with positive values and contributions to their communities. During the course of the film, even when Ann is exposed to accusations against her father, she forcefully defends him without faltering. Moreover, she willfully overlooks any evidence that might undermine her father’s innocence. She finally succeeds in bringing about his acquittal.

The cases against Nazi war criminals raise several questions. Does the statute of limitations apply to war crimes committed during the Holocaust? Is there today a consensus regarding the degree of responsibility these people have for their wartime actions? Who is involved in this debate and what motivates them?

In 1961, these issues were raised during the Adolf Eichmann trial in Israel. This trial was widely covered in the local and international press. Hannah Arendt (1906-1975), the noted political theorist, covered the trial on behalf of The New Yorker. A German native, Arendt left her birthplace after the Nazi rise to power, and immigrated to the United States in 1940. Arendt was present during a number of the Eichmann trial sessions, and her journalistic writings on the trial have been collected in the book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil,1 originally published in 1963.

In the interest of brevity, Arendt essentially doubts Eichmann’s personal responsibility for the murder of Jews. In the courtroom, she perceived a somewhat gray bureaucrat, and while he had taken initiative in carrying out his duties, in no way was he a policy maker or agenda setter. In Eichmann, Arendt saw the embodiment of his official title “Senior Expert on Jewish Affairs”. The “humanization” of Eichmann by Arendt was a central part of her greater political theory. In her academic writing, Arendt focused on the sources of totalitarianism,2 the roots of which she saw in antisemitism, nationalism, and imperialism, as well as within the totalitarian vision itself. Therefore, to Arendt, the question of Eichmann's guilt was secondary to the wider discussion of totalitarianism. In her view, totalitarianism takes control of individuals and social systems in stressing interests “greater” than those of the individual. Thus the individual exists only as part of a powerful and all-inclusive system and is, in a certain sense, a victim of the totalitarian system.

Arendt’s criticism caused a great deal of debate in the American press, as well as in Israeli and American intellectual circles. It is worth noting, however, that this debate over the culpability of the individual – Eichmann, in this case – took place less than twenty years after the Holocaust.

The question of responsibility and guilt arose again years later, during the John Demjanjuk trial in Jerusalem. This same question can also be raised within the context of the character, Laszlo, in the film. In the case of Eichmann, he was a high-ranking Nazi bureaucrat, with a critical role in organizing the practical elements of the “Final Solution”. Unlike Eichmann, who was known as a “desktop murderer”, Demjanjuk and Laszlo were “field men” – people who had committed their crimes with their own hands. Demjanjuk was accused of forcing his victims into the gas chambers. In Laszlo’s fictional case, he was accused of murder and rape as part of the Arrow Cross Party’s actions in Budapest.

Though the nature of responsibility is different in each of these cases – Eichmann was responsible for the murder of millions, whereas Demjanjuk and the fictional Laszlo were “only” responsible for tens or hundreds – the questions of responsibility, guilt, and the statute of limitations remain.

Another point of comparison between the cases is in the sphere of public opinion and criticism of the trial. With the passage of time, most of the Holocaust-era war criminals have passed away. The survivors who testify against them are elderly, and their testimony – years after the events have transpired – is called into question by the defense. In this article I’ve mentioned the matter of proper identification, which had been questioned both in the Laszlo trial, and in the real-life trial of Demjanjuk. The survivor testimony in the film is worth viewing, especially the testimony from a witness who had seen the murder of his own family members on the Lanchid Bridge in Budapest, while in a work detail. When presented with a photograph of a young Laszlo, he is still incapable of looking at it directly – and when he finally does, it is only briefly, and with great difficulty. The next witness is a female survivor who had been raped by Laszlo and his cohorts. Her determination to face him brings Laszlo to a physical breakdown. At this point, even the most deep-set of denial mechanisms cannot protect him.

While on the subject of the accused's physical state, I’ll also mention that the frail health of many war criminals has often been raised in courtroom proceedings, public discourse, and in sentencing. Here too we must ask ourselves about the sources for this sympathy for the criminals’ medical condition, criminals who today appear to be “harmless old men”.

Following testimony that might shed new light on the trial, the court travels to Hungary. During her trip, Ann meets a figure from her father’s past, and is ultimately confronted with her father’s guilt.

The second generation of Holocaust victims is a subject that demands our attention. At the center of this film is the conflict involving the second generation of the perpetrators and their parents; many difficulties and complexities are revealed. As the film progresses, we observe the gradual and engrossing process that Ann undergoes while discovering her father’s guilt. Her father’s denial of his personal past is paralleled to her own denial of this past. As Ann reads the initial material from the investigations, it is clear that she feels empathy toward the victims and their stories and is horrified by the cruelty of the crimes attributed to her father. At the same time, she fulfils her responsibility as a legal counsel and doesn’t shrink from confronting the witnesses in an attempt to undermine their credibility. She steadfastly refuses to listen to her legal secretary who finds facts that could cast light on her father’s past. Thus, the moment of revelation and the ensuing confrontation with her father is the climax of the film. Laszlo refuses to admit to the truth throughout this confrontation. With her concluding words, she asks her father: “How could you do this to me and to Mikey?” With this question, it is clear that she is hurt and angered by her father’s behavior, and this leads her to important decisions regarding her father and the court case. She severs all contact with him and hands over the incriminating evidence to the prosecuting team.

Thank you for registering to receive information from Yad Vashem.

You will receive periodic updates regarding recent events, publications and new initiatives.

"The work of Yad Vashem is critical and necessary to remind the world of the consequences of hate"

Paul Daly

#GivingTuesday

Donate to Educate Against Hate

Worldwide antisemitism is on the rise.

At Yad Vashem, we strive to make the world a better place by combating antisemitism through teacher training, international lectures and workshops and online courses.

We need you to partner with us in this vital mission to #EducateAgainstHate

The good news:

The Yad Vashem website had recently undergone a major upgrade!

The less good news:

The page you are looking for has apparently been moved.

We are therefore redirecting you to what we hope will be a useful landing page.

For any questions/clarifications/problems, please contact: webmaster@yadvashem.org.il

Press the X button to continue