- The “Maccabi Hatzair” youth movement was founded in Czechoslovakia in 1929. It was formed as an educational, unaffiliated youth movement based on values of Judaism and Zionism.

- Victor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning, Beacon Press, Boston 2006, pp. 76-77.

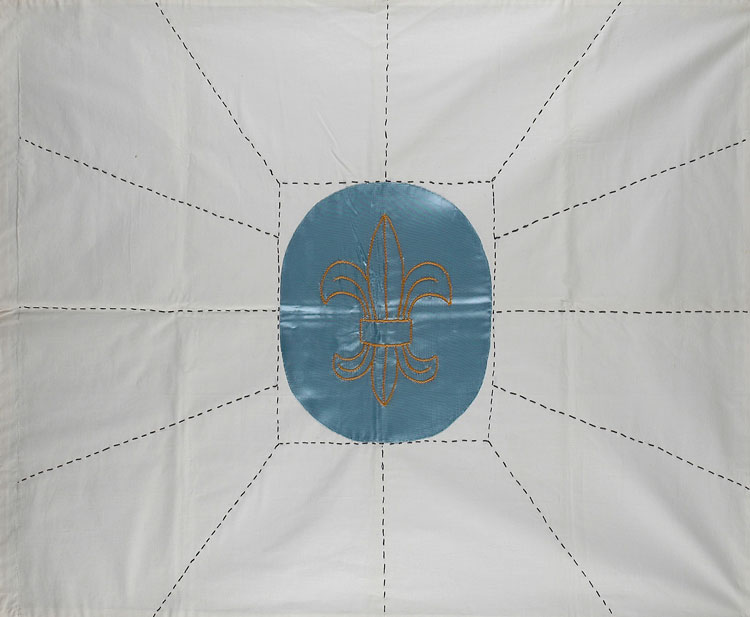

On the eve of the deportations to the death camps, a group of youths and their counselors participated in a ceremony. In this ceremony, their Hachshara (training camp) flag was cut into twelve pieces and distributed among the counselors. They swore to reunite in the land of Israel and remake the complete flag from its pieces. Ultimately, only three of the twelve leaders would survive the Holocaust, and of these only Anneliese Borinski managed to bring her piece of the flag to the land of Israel.

After the Nazi rise to power in Germany, the Zionist movements increased their efforts to hasten the immigration of Jewish youth to the land of Israel. In order to prepare them for life on the kibbutz in Israel, agricultural training farms (Hachsharot) were set up. One of these training farms, belonging to the “Maccabi Hatzair”1 youth movement, was set up near the town of Ahrensdorf, not far from Berlin.

This farm became home for youths aged 15 – 17, and their counselors. Their training focused on farm work, lessons in Zionism and identification with the land of Israel. These young adults would work in the fields until the late afternoons, at which time lessons began, covering subjects such as Jewish History, Bible, and Hebrew language. Debates and cultural activities took place in the evenings. Youths that reached 18 years of age, attempted to find ways to immigrate to the land of Israel.

In spite of the Spartan conditions and simple food, the youths were enthusiastic and, like most youth movement members in those days in Europe, they identified fully with Zionist ideals. Living a cooperative lifestyle bonded the youths together, and the separation from their families turned their leaders into surrogate parents and strong role models.

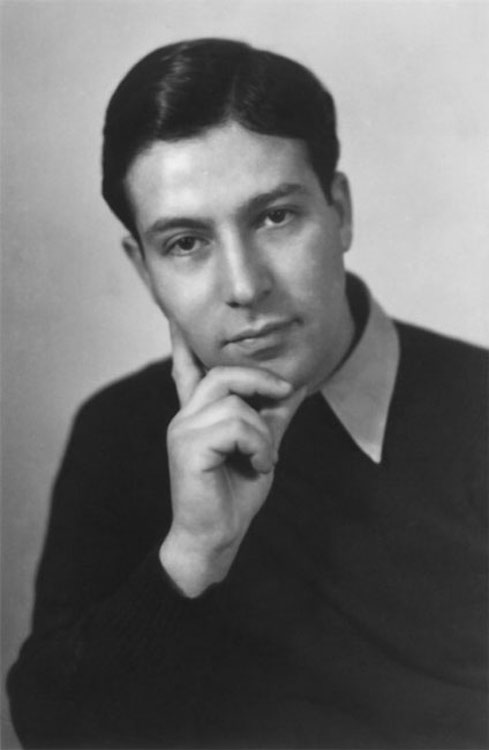

One of the youth leaders at Ahrensdorf was Anneliese Borinski. She was born in 1914 to a Jewish family that had little Jewish or Zionist affiliation, but the increasing expulsion of Jews from German educational institutions, forced her into a Jewish framework. After completing studies in education at the Jewish Seminary in Berlin, she came to Ahrensdorf as a Maccabi Hatzair youth leader at the age of 23. Though Anneliese was not previously inclined toward Zionism, she learned about the land of Israel together with her charges and came to identify fully with the Hachshara’s ideals.

At the outbreak of war in 1939, the conditions in Ahrensdorf became increasingly difficult until finally the Gestapo actively took over the farm. In spite of this the youth continued for a time to live in a protective bubble, as all the internal activities continued to be managed as before. Anneliese Borinski remained there until 1941 when the training farm at Ahrensdorf was closed. The leaders and the youth in their care were transferred to Neuendorf Camp, where assorted groups of Jews had been concentrated and forced to do hard labor under Gestapo supervision. In spite of the situation, the Hachshara members continued to demand of themselves the discipline they had maintained in Ahrensdorf.

The Maccabi Hatzair flag played an important educational part in the ceremonies of the Hachshara. The flag symbolized the essence of all the ideals in which they believed. It was first cut in 1942 when the youths were transferred to the Neuendorf Camp. The lily, the “Scouts” symbol and the flag’s central motif, were cut from the flag in order to send it to the movement members who were already in the land of Israel. It was sent with two youth leaders from Israel who were allowed to leave Germany and return home. The women, Bracha Brosh and Chana Blumenkopf had traveled to Poland to visit family, where they were stranded when war broke out. In the process of attempting to return home they found themselves in Neuendorf Camp, where they served as role models and gave inspiration and hope to those who wished to go to the land of Israel. Anneliese Borinski relates in her testimony:

“One day, before the Channukah of 1941, they finally received notification that they could return home. We took their leave in a festive assembly…but what could we send with two women who were returning to the homeland – to the land of Israel? What could we send as a clear symbol that would express to our Chaverim [fellow movement members] there that we hadn’t forgotten them and so we would know we hadn't been forgotten. We didn’t hesitate at all. The answer was obvious. As we stood in formation with the flags before us, A. cut out the Scout lily from the heart of the flag and presented it to Chana as a memento from us for the Chaverim in Israel. We sang “Hatikva” and “Seu Tziona” and paraded off. It arrived with them in Israel. Together with the flag’s heart they brought our story directly to the “Gordonia – Maccabi Hatzair” movement.”

In 1943 the situation in Germany deteriorated. Rumors circulated daily about people who were abducted or deported. Among them were many of the youths’ parents, deported to Poland or to prisons in Germany. After the murder of Alfred Selbiger, the head of Maccabi Hatzair in Germany, despair set in, as well as a feeling that future events might separate the leaders from the youths. Lists started arriving at the camps with the names of youth members slated for deportation.

Finally a list came with the names of all those still remaining in the camp. On the final night in Neuendorf, a ceremony was held in which the flag was divided among the remaining youth leaders of the various groups. The goal was to reassemble in the land of Israel and recreate the flag. Anneliese Borinski’s testimony:

April 7th, 1943

Outside are the Gestapo guards. We are forbidden to go out into the yard. We commence with our final assembly. Once again, everyone is dressed in blue and white. We sing. Flags are brought. One flag is missing its center. A’ takes this “broken hearted flag” and cuts it into 12 pieces. These he distributes between the three female and the four male youth group members who will be responsible for each group and the one who will be responsible for the “mixed race” group remaining in Germany, and one piece to each of the four leaders!!

At this opportunity we promised each other that we would each take care of the pieces, and that we would join the pieces together once we were reunited in the land of Israel. This torn piece of flag that was given to me, I carry it with me until today. It remained with me through all the body searches and all the selections in Auschwitz. I must continue to carry it with me because I promised and that promise is what drives me…”

In mid-1943 the remaining youths and their leaders were deported to a prison in Berlin and from there they were sent to Auschwitz. Later, they learned that their deportation had been part of the massive round-up of German Jews that was carried out “in honor” of Hitler’s birthday. In Auschwitz, the youths were divided into different groups, but due to the determination of the youth leaders they managed to keep in contact and pass information between them. Anneliese, who took her responsibility for her wards seriously, tried to care for them and even made them small gifts for their birthdays:

“We realized that it would be important to stay together - the Maccabi Hatzair group with our ideals and our aim to eventually reach the land of Israel and to bring the pieces of the flag with us. In our naivete we thought that this was the most important thing. In the early days in Auschwitz we certainly didn’t realize that it was a matter of life and death, and maybe it was good that we didn’t know.

On the first day we endured one torture after another in Birkenau, [so much] that I think it would have broken us if we hadn’t been so concerned with these ideals that we held on to and that gave us strength…we were so focused on them, that nothing else seemed important to us – in spite of all that happened to us.”

Throughout her imprisonment in Auschwitz, Anneliese kept her piece of the flag, despite the difficulty of hiding personal items:

“...The only personal belongings that we were allowed to keep were our shoes. That was very important, for instance, as I realized immediately when we had to undress - so I hid the piece of flag under the sole of my shoe, - it was terribly important to me to hide it somewhere safe. It was there for a long time until later, sometimes there were what was called “visitations,” i.e. a very thorough body search – and then I hid it in different places, because the S.S. knew of course that it was possible to hide all sorts of things in our shoes. “

The Maccabi Hatzair youth - boys and girls - were imprisoned in Auschwitz for nearly two years. They worked at slave labor, in conditions of starvation, cold, and humiliation. Many of them succumbed to the harsh conditions. Anneliese Borinski left Auschwitz on the death march in January 1945 together with her Chanichim. They escaped from the convoy in the area of Leipzig and reached the areas liberated by American forces.

Anneliese immigrated to Israel in 1945, settling in Kibbutz Maayan Tzvi. Her married name is Ora Aloni. Until her death she worked as an educator. In trying to explain her survival:

“…and if today I want to "audit" myself.. or someone asks me – and of course they asked - how did we manage to survive the camp, a concentration camp, a death camp! How did we manage to come out of there?

I think I can explain it this way: I think that there are six main factors: the first, I think, is the strongest, the mutual support we received from each other, though we were split up, in any case we were among companions. We were always one for all and we felt that the others were for us. Even when we weren’t all together, we always felt connected and never completely alone. At least three or four or five were together. That helped a lot, practically as well as emotionally. It gave us a lot of strength and for me, there was also the sense of responsibility, the feeling that I had to do everything to get to somewhere where I would be able to see who had remained alive and to try to get everyone together again and if possible try to reach the land of Israel.

The second factor: was definitely the hope and the expectation that was impossible to erode, that one day things would be better and we would arrive in the land of Israel, that we must get there! This was manifest in each small party, each Oneg Shabbat, on Yom Kippur, I don’t know, in promises that we made and expressed in symbolic items that we preserved so carefully, in the flag, the piece of flag that I continued to carry with me.

The third factor: maybe more complex, I would say: a particular personality trait is part of it and the power to adapt, quickly were sometimes absolutely necessary, as well as luck!…”

- 1. 1

The central part of the flag, brought by Chana and Bracha, the two leaders who had returned to the land of Israel in 1941, was preserved for a time in the Maccabi Hatzair movement archives. Today it’s whereabouts are unclear. Anneliese’s piece of the flag is the only piece distributed among the leaders that was brought to Israel. It was preserved in Kibbutz Maayan Tzvi until Ora Aloni’s son passed it on to Yad Vashem in 2007. The surviving youth members who reunited in Israel, prepared a replica of the original flag and embroidered it along the lines that divided the original flag into twelve. This replica is also preserved at Yad Vashem.

Points for Classroom Discussion:

- While in Hachshara, the boys and girls lived their lives independently, far from their homes and their parents. What needs was the Hachshara framework meeting?

A: The Hachshara provided an alternative to several basic environments – home, family, and school. The activities that took place – the studies, work, social and cultural activities – involved all facets of life. - With the deportation of the youth to Neuendorf, the group was split among the various sub-camps of Auschwitz. How was the group’s strength and fortitude shown at this stage? Where do we see care of the guides for the youth?

- “Broken hearted flag” – the flag as symbol: what do you think the flag meant to the Hachshara members?

A: The flag represented the group’s shared values and goals. It also represented the group member’s personal responsibility toward each other and their sense of unity. Later, when the members had been separated and deported to Auschwitz, the flag had come to represent life itself. - In this context, you can relate to the ceremonies the Hachshara members would perform, with the flag at their center. For them, the ceremonies marked an oath of mutual commitment

- The flag as catalyst: In his book Man’s Search For Meaning, Victor Frankl writes:

“..any attempt to restore a man’s inner strength in the camp had first to succeed in showing him some future goal. Nietzsche’s words, “He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how,” could be the guiding motto for all psychotherapeutic and psychohygienic efforts regarding prisoners.

Whenever there was an opportunity for it, one had to give them a why - an aim -for their lives, in order to strengthen them to bear the terrible how of their existence. Woe to him who saw no more sense in his life, no aim, no purpose, and therefore no point in carrying on. He was soon lost.”2

In our story, the flag fragment gave motivation to endure, to overcome difficulties, slave labor, and the terrible cold, hunger, and humiliation. For Ora Aloni, reconstructing the flag became a goal in and of itself, and clinging to the idea motivated her to hold on and survive.

- 2. 2