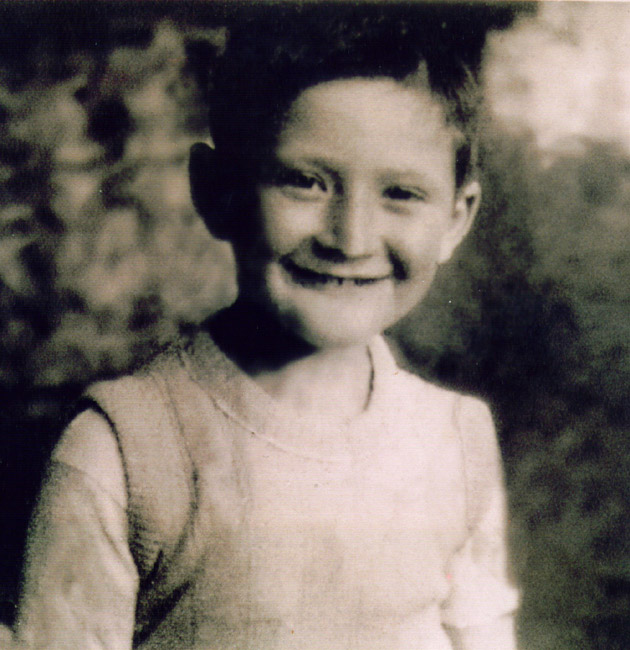

Early Years

I was born on 11 November 1932, which means I am already over seventy-eight years old. My parents came to France from Poland. Before then they were in Italy for a few months, because they wanted to make aliyah, but they didn’t receive an immigration certificate. So, many many years later, I am here and able to fulfill their wishes. Nobody would have thought then, that I would be here in Israel, and my father would have perished in Auschwitz.

I grew up in a poor family and was an only child. We lived in a poor, working class area of Paris and I went to school. My parents spoke Polish at home between themselves, and I think I spoke with them in Yiddish, but more in French, which they had learned. I don’t remember my father. The last time I saw him was in September 1939 when I was not yet seven years old. I don’t remember him – what I remember is from photographs. I don’t remember his voice; I don’t remember the color of his skin, because you don’t see this in a photograph.

1939: World War II

When war broke out in September 1939 I was already in a children’s home in a small town called Montmorency. It seemed to me that I was the only child there from France. All the others were from Germany and Austria, as this was already 1939 and after the Anschluss.

Although my father was not French, he volunteered for the French army. He was put in a regiment for foreigners, but basically he didn’t do anything in the army, because the French quickly surrendered to the German forces.

In May 1940, when the Nazis began to get close to Paris we were moved to the center of France to a place called Le Masgellier. The home was part of the children’s welfare organization OSE (The Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants). By the way, this organization operated in Russia and Poland after World War I not only to save orphaned children from the war, but also to save them from the Spanish flu epidemic from which more people died than those killed during the war. In 1939 more homes were opened in France to help Jewish children, and I was in one of these homes.

Children’s Home in Southern France

Luckily, we were on the “right” side of the border. France was divided into two parts. We were in the southern part under the Vichy regime, known as the “free zone.” Though we were technically free under the Vichy regime, we realized very quickly that it wasn’t so free for Jews.

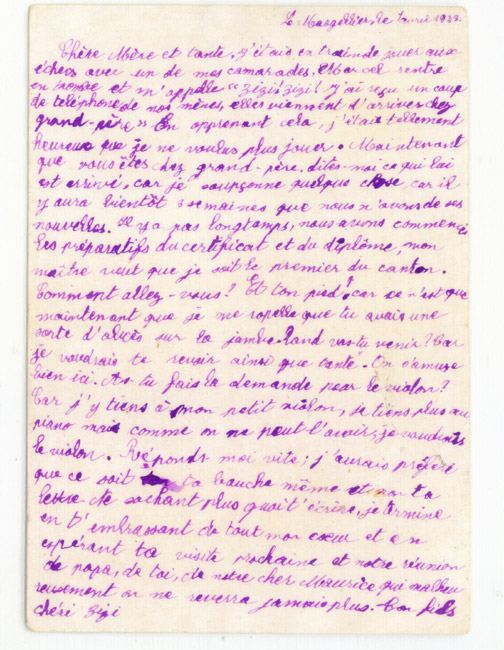

So, I was in the children’s home, and I have a lot of photographs from this time, but there was a period of time when I didn’t receive any letters from my father. I wrote to my mother and asked her if I could return to Paris to see my father, and how this would be possible if I was in the south and she was in Paris. My mother knew a railway inspector who worked on the trains. He took me to a railway station at La Souterraine. After that he took me over the border and put me in the train car that held the packages being delivered from the South to occupied France and I was hidden among the packages.

A Visit Home to Paris

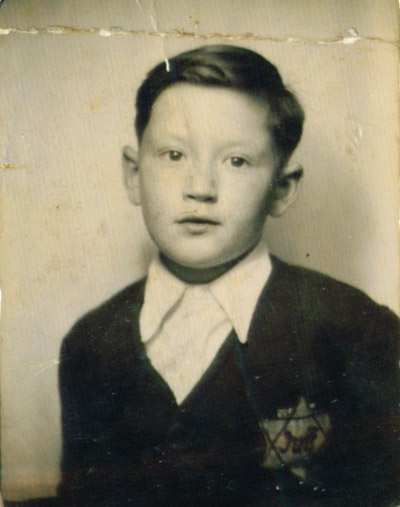

After we crossed the border they took me to my mother who was living in a working class district. There were many foreigners living there – Spanish, Italians, Poles, and others, and there was no antisemitism. That was in March 1942. Afterwards, in June, I had to walk around with a yellow star like all of the other Jewish children. I went back to Paris for a month, where I had to wear the star, and on July 16, 1942, there was an “aktion,” when they rounded up everyone, but on the first night they did not come for us. My mother was outside and was told to hide because of the police [Germans did not do any of these activities. It was the French police who rounded up its Jews.] Where did we hide? We hid with a non-Jewish neighbor. We realized it wasn’t safe so we began hiding with different non-Jews every night. Eventually we went to a village, which I recently realized was the same village that my father was in before being deported to the camp. I’m talking about July 1942. They were working for the farmers because all of the French soldiers were stuck in Germany. They were in need of laborers and my father was working there. We went with my mother to hide with the same man who was helping my father. My father was deported to Auschwitz in June 1942 so we were there for a month without my father. My father did not return after the war, and I don’t remember him. After the war, I remember I saw a man who looked just like my father and I ran up to him and looked at him just to try and remember what my own father looked like.

Back in Vichy France

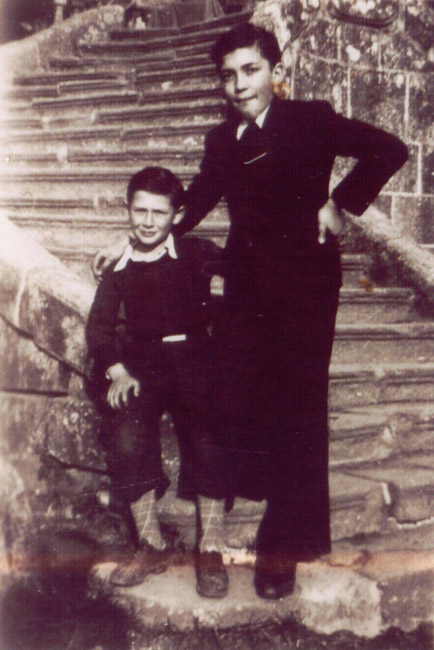

We needed to leave Paris quickly and we went from village to village until we reached the border between occupied France and Vichy France and when we crossed, the French stopped us on the free side. I was nine and a half years old, and I was with my cousin who was fourteen and a half. While I had spent two years in a children’s home, my cousin was coming straight from Paris. My mother told me to return to the children’s home, because she understood that it was dangerous for me to be with her. She heard that people were being sent to French concentration camps in the south such as Gurs. I took my cousin who didn’t know the area and we took the train to the organization that I was familiar with. We were there until May 1943.

My mother was arrested by the French and taken to the concentration camp Rivesaltes, in southern France and then to Gurs and from there my mother and aunt managed to run leave by paying bribes and the like. I was a French citizen so I wrote a letter to my mother and enclosed some money to try to help her. I didn’t know during the war where she was, but we continued hoping. My mother was freed from the camp in May 1943. She lived with my aunt in a small town in southern France, where a few Jews lived, including the family of Claudine Rudel who works at Yad Vashem [see some of Ms. Rudel's recollections - Ed.]. Once they were freed, I left the children’s home and went to stay with my mother, but within one month, the organization split up because children were being hunted and it was dangerous. In every place I was, I was lucky. I left every place at the right time. I also had luck that my mother understood that to save a child you had to separate from him. That was the difficulty of motherhood, like King Solomon’s decision. Instead of losing the children, they said, “go” or “I will give him away.” This is a modern day King Solomon story, like the mothers who threw their children out of trains heading for Auschwitz. It is an understanding that the future of the world relies on children rather than adults. When I speak with people I tell them that no one knows what strength a child is capable of. Many of the camp survivors were teenagers around the age of fifteen, who in some way were able to hold on. We need to give children the tools but not the boundaries. We shouldn’t cage them in because you never know what they will have to do. Even today, I test myself by going into the desert by myself without supplies. I know how to find water and food, and how to navigate by myself. I have a friend who recently passed away, but he always had a piece of bread with him. He was also a child hidden at a children’s home, and he wanted to always know he had food to eat should he need it.

Was this because you were hungry during the war?

I remember that we did eat in the children’s home. My cousin and I sent bread to our mothers when they were in the concentration camp. To ensure that the bread wouldn’t go bad during the journey, we put garlic on it, which gave it the smell of a hot dog, but protected it and this was another example of children helping their parents.

1943 Until After the War

Afterwards, when my mother and her sister were freed from the camp in 1943, we left the home and we went with them to the most beautiful village in the south. Many Jews lived there, religious and not religious. Because some of the Jews knew how to work the land, we even made shmura matzah1 in the village. The first Hebrew word I learned was from a Romanian farmer in France during the war!

In the village, I became an expert in stuffing geese. After they were killed, we’d send the geese to many different villages where Jews lived, such as Nice, and we lived off the income. In this way we passed through the war.

After the War

In May 1945, we returned to Paris, which had been liberated in August 1944. My cousin and aunt came to live in our modest apartment with us. It was a damp ground-floor apartment with no furniture. We suffered through one of the coldest winters that France had seen, sleeping on the floor. One of the first things I remember is that I quickly joined a youth group and that depicts one of the most important principals that parents wanted to teach their children, to have a Jewish life and be surrounded by a Jewish community. They sent us to school right away. In all generations, Jews know the importance of study and learning. I went to a Jewish school but before it became a school, it was a place where food and clothes were handed out. I went there to get a blanket and from that my mother made me a coat.

We finally realized our fathers were not returning and my mother sent me to ask the one man who returned, what happened to our fathers, and I hated this man because he came back from the camps. It was difficult. As time went on, as I learned what happened during the war, I began to realize that even though that man may have come back, he had no wife, no family, nothing. After the war, many Jews arrived in Paris from the east, from Poland and Russia. We had a constantly revolving door for different relatives and survivors who came to Paris seeking new lives. They stayed with us and then moved on to somewhere else. I went to study in Paris, and became a doctor. I married an Israeli woman who was visiting France from Israel. I think I married her because she was Israeli and my dream was to make aliyah (immigrate to Israel). I was in all of the different youth movements, Bnei Akiva, Scouts, the Bund, and the Communists. I finally moved to Israel. I had been here twice; the first was in the 1950s when I was seventeen. I think the name of my ship was Anna Maria. We spent 8 days at sea starting in Marseilles. We came to get to know the country.

Were you religious growing up?

I didn’t know what was religious or not religious. I had a bar mitzvah. I had a private Hebrew and Judaic Studies teacher. I remember that we sat for hours learning the prayer Shema and the Hebrew grammar of the words in that prayer.

When I arrived in Israel, I was already a doctor and I went to live on a kibbutz. There was one particular older woman who gave me a book written by S.Y. Agnon. It was the first book given to me in Israel and helped me improve my Hebrew. I loved the story and since then I have acquired all of Agnon’s books.

You spoke about your mother and where she was during the war. How did she hide you and find you?

My mother always knew where I was because I wrote to her. I am of the generation where parents did not speak much to their children. My mother did not explain so much to me after the war.

How many children were in Chateau Le Masgellier?

150, something like that.

Did you ever get the sense that the situation was dangerous?

Definitely not. I was a child. I was a child among children. We went to school, we worked the land, we sang, celebrated national and religious holidays. I remember a play that I performed in Yiddish. We were ten children who performed in this play. I remember a few things from there. That place wasn’t religious but there was a home for religious children not far from us.

Did the non-Jewish population who lived around the area know about this place where Jewish children were hidden?

Yes, the place was in central France. It was working class, not a rich area where it was always known that good people lived. They were open to receiving people and in this area there were many Jewish children.

Were there times when Germans entered to look for Jews?

Everything depends on what time we are talking about. I am talking about the period until May, 1943. The Germans did not come even though they were present at this time. It began to be difficult in March or April, 1943. I know this because my cousin who was fifteen at the time told me that in the evenings, the adults slept in different locations to spread them out. They returned in the morning but this made it easier to hide other people who weren’t of French descent such as from Russia, Poland, and Austria. As you know, on November 11, 1942, the Germans invaded the south and there was one German Jewish child, named Richard who was fifteen and when he heard that the Germans were coming he ran from the children’s home and said, “I don’t want to go to Dachau.” This was the first time I heard the word “Dachau.” He hadn’t been there but his father was there. You know, the camp began in 1933 so he knew that it was a horrible place and wanted to flee when the Germans arrived.

Did you understand what was happening? Why they had to send you to the south? Why you had to separate from your mother?

No, I did not know. I missed my mother a bit but when you are with other children and staff, you are constantly busy with studies and other activities. We worked the land surrounding the village in order to get potatoes or carrots. We created things. We went to school. There was a non-Jewish French teacher there and a few years ago I received a letter from him. It began: “I am eighty years old. I was a teacher in the children’s home and I remember one child named Zizi. Maybe this is you. I have your picture.” I went to meet him again. I asked him about the war years. He said I was his best student and that I could translate for the German students or ones who did not know French very well. This was the first job he was given after finishing school.

And it wasn’t dangerous for him to teach in this school?

No, this wasn’t in hiding! Everyone knew that this place existed. They knew the nationality of all of the children.

Your grandfather was in Paris the whole time?

No, my grandfather was in the south, in Toulouse with different families. He was a religious man with a long beard.

Out of the children in the home, did most of their parents come back?

I don’t know because from the moment I left, I lost touch with the other children. I did run into one of the other children later.

My mother saved all of the photographs and things from my childhood. We lived together with my grandfather. It was only after my mother passed away that I moved to Israel.

What I want you to understand is that a child in hiding makes things sad and dark but at the end of the day, he is a child and this makes everything appear different. I remember picking carrots and potatoes. I don’t think I understood why I was there. I knew that my father wasn’t at home and my mother was alone but for me this wasn’t new because already in 1938 I always went to a summer camp by myself. This was like summer camp for an extended period.

My mother didn’t speak about this period even after I grew up. Parents spoke a language that their children did not understand. There wasn’t the kind of closeness between parents and children that exists today.

- 1. Pujaudran, France, A photograph of the Rudel family in the midst of baking Matzos, 1943. See some of Claudine Rudel's recollections.