Alexander Bogen

Alexander Bogen was born in 1916 in Dorf, Estonia to the Katzenbogen family. When he was one year old, his family moved to Vilna. Bogen studied painting and sculpting in the Faculty of the Arts at Vilna University. After Lithuania was captured by the Nazis, he joined a partisan unit at Narotz Forest and infiltrated the Vilna Ghetto shortly before its liquidation. In the ghetto, Bogen joined the United Partisan Organization (PPO), organized and smuggled groups of people from the ghetto to the forests, where they joined non-Jewish partisans. Bogen commanded one of the units who went on missions which included laying mines on railroad tracks, sabotaging German armories and distributing information about the mass murder. During his activity, Bogen drew the places, the people, and the events around him.

We met with Alexander Bogen in his studio adjacent to his house in Tel Aviv. The studio is packed with paintings from different periods in his life: one is from when he studied in Vilna, several paintings that survived the war period, and some from his years living in Israel. He welcomes us with hands stained by blue oil color.

"As a boy, in primary school, I was known as an artist," he says. "Between the wars I lived in Vilna, where I was educated and attended the Academy. Honestly, it has to be said that intellectually we were detached from the western, French, art. The approach was characteristically academic and the teachers didn't relate to the modern art of the period. In the spirit of the academy, I was a classicist as well. After the war, it was after I immigrated to Israel, I was sent to the Paris Art Academy, where I was introduced to modern world art headed by Picasso, who is now considered a classic. They were the most advanced and led the French art in terms of principles. In that spirit, I also began to examine myself, and moved to more advanced art."

Bogen married before the war started, while in his 20's. When he was 25, Lithuania was invaded by the Germans.

“The war actually broke out on my fourth year in the academy. We tried to escape to the east and we got to Minsk, but the German tanks stopped us and we found ourselves in Svintsyan Ghetto. When the ghetto was moved to Vilna we had to move with the Svintsyan residents. This was according to the German plans. The entire Jewish population from all the ghettos in that area was taken to Vilna and divided into two groups: one made up of those who wanted to get to Kaunas – this group was immediately sent to Ponary for execution. The people who wanted to get to Vilna arrived in the ghetto and stayed there until it was liquidated. Some were taken to a concentration camp in Estonia, and others were killed when the Vilna Ghetto was destroyed in 1943."

Did you know other artists in the Vilna Ghetto?

When I was in the Vilna Ghetto, I asked Abba Kovner to introduce me to other Jewish academy artists. We walked though the alleyways and climbed up to the third floor. The door opened and we saw painter Roza Sutzkever, who was one of the leading artists in the city before the war, standing by her easel and painting a portrait. And she asks me, "Alexander, tell me, did I capture my model's smile?" She was very happy despite being hungry. And I asked myself: "Damn it, how is it that when I look – not at myself, but at the prospect of certain extermination – how can this be? How is it possible that in a person about to die this yearning for artistic expression is stronger than life?” There was another painter there, Hadassa Gurevich; that was a few days before the destruction of the ghetto. They turned to their friend, a fellow student from Germany, and asked him to help them. He agreed and told them to come to his house outside the ghetto. When they arrived, SS men were already there, who arrested and then deported them to Ponary for execution. Roza Sutzkever was highly respected, and she and Hadassa were sure he'd help them. That was German ethic.

Have you met Abba Kovner before?

I met him before the war. He tried to enroll in the Art Academy, wanted to become a painter, but the antisemitic hostile environment discouraged him. I was an advanced student. I tried to help him, but he left and turned to poetry.

Did meeting Roza Sutzkever and Hadassa Gurevich influence your desire to paint? Did you paint in the ghetto?

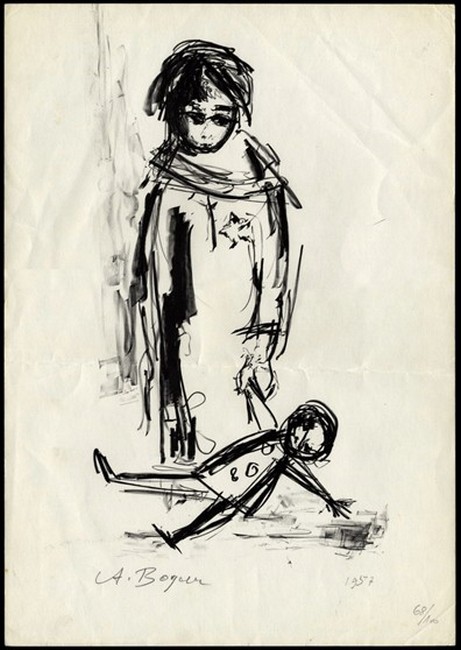

When I was in the ghetto, I saw a little girl with a doll standing next to a wall. I asked her where her parents were. They had already been taken to concentration camps and she was standing like that, not crying, and holding the doll's hand. And I, a man armed with a handgun and two grenades, a strong man, stood in front of that miserable creature, and I couldn’t help. I felt very bad. I was a man and the feeling that you can't help this little girl… the only thing I could do… I took out my pencil and drew her, almost subconsciously. After the war I asked myself, "What have you done? How could you do such a thing and act so instinctively?" Maybe it was a feeling of… let's say, a sense of survival, a subconscious need. I didn't know why I was doing it.

You mentioned Gurevich and Sutzkever. What can you tell us about the cultural life in the ghetto?

Look, this was part of Gens' (head of the Vilna Ghetto Judenrat) view, to restore the ghetto and a sense of safety… there was a Jewish theater, there were painters, musicians. Gens encouraged it, to convey to the Jews the feeling that there is a possibility for a peaceful existence and there is no need to be scared.

How did he support it in practice?

There was a theater and Gens allowed it to keep running. There was an evening dedicated to Sutzkever, and poets would get actual subsistence like food.

Were you part of it?

I didn’t have anything to do with that. I was preparing an organized escape to the woods. To get weapons. This wasn't easy. It had to be bought with gold. People about to be executed engaging in culture and art, that was a dissonance to me, and it was intended to divert the attention of the Jews from the real situation. If there is a theater it means that the ghetto might continue to exist. If the Germans are allowing this, that means that there is no danger. I saw it as an attempt to dim the sense of danger.

Did you know Gens personally?

Yes, I knew him personally. When I came from the forest I met him for a talk and I told him that all his efforts to produce for the German army is a mistake because the Germans’ fundamental idea was to exterminate all the Jews everywhere, to destroy the ghettos.

You think he didn’t see that? He didn’t understand it?

He thought that if we'll work with the Germans and manufacture clothes and food it might help us survive. But it was fundamentally wrong, and I told him that. Gens said to us, "Listen, I am in contact with the PPO. If the Germans will come to destroy the ghetto, I'll join the resistance and even head it. In the meantime, we must do everything to maintain the situation as it is, and we might be lucky and be liberated by the Soviet army.”

What was your impression of him as a human being?

He was handsome, manly and he was also an officer in the Lithuanian Army before the war. He would stand before the Germans with dignity. And the Germans responded, they needed someone who would really work for them and wouldn’t allow an uprising in the ghetto. But a few days before the liquidation of the ghetto they invited him to the Gestapo and killed him while he was there. His concept of working for the Germans and that way to extend the existence of the ghetto was proven unfounded. The idea of the Nazis was to wipe out every ghetto, every Jewish community, to exterminate all the Jews in Europe.

I - and others in the ghetto - refused to accept Gens' attitude, but we didn't agree with the PPO either. The PPO decided at the time - Abba Kovner stated it - that the resistance would not move out of the ghetto and into the forests as long as the ghetto existed. If the Germans were to start operations in order to liquidate the ghetto, the PPO would in return pull out their weapons and fight the Germans. I told Abba Kovner that strategically it didn’t make sense, and that it would be impractical because the modern weapons it's enough for one tank to attack the Ghetto. Less than 200 people can't fight an experienced army. According to Abba Kovner they would take arms only if a liquidation started. Once they knew the end was near the PPO was ready to move to the forest. Only then did they abandon the idea of fighting in the ghetto, and agreed to go and fight with the Partisans. We were a group of people who came from Svintsyan who suggested to Kovner to take resistance members out to the forest. Wittenberg and Abba Kovner were against it, so there was no choice but to get organized privately, without the PPO. We went out and joined the "Revenge" unit, and later returned.

So you entered and got out of Vilna Ghetto twice?

The first time was when they took everyone from Svintsyan to Vilna along with me, my wife and her parents. The second time I left with a group of people from Svintsyan to the forest, and while we were there I already asked to leave, and to go to Vilna to get more resistance fighters.

Rachel, your wife, escaped with you?

Not the first time, but the second time she was with me, yes. She was in the ghetto. I went with the group - without my wife. Of course, the separation was very hard, it's one of the greatest tragedies: A father separated from his children, a husband who leaves a wife behind. That's why not everyone decided to leave. Their conscience didn’t allow them to leave their families.

Rachel joined me later. When I came back later to help the youth escape, I took her, too. I took her mother as well.

How did her mother manage in the woods?

There were camps for older Jews. She was in one of those, in the woods. We would join them once in a while, and give them food. We would go to the villages and take everything we needed to survive. Sometime we took cows, sometimes clothes - that was the basis of our existence.

So you were responsible for providing for those who hid in the woods?

We would help them, yes.

As a partisan you had the fortune of being in a Jewish unit.

I was one of the leaders of the Nekama (revenge) Jewish unit. We were an independent unit, we felt free. We spoke different languages, also Yiddish. We would meet after missions and sing in Yiddish. A short while afterwards, Stalin gave direct order that no armed units of Jews should be formed, but that they should belong to the units of the republics where they once resided. In fact, Stalin was an antisemite and his policy of not allowing Jewish groups to organize is what shut down the Nekama group. I was then made the commander of a special mission unit, mainly of intelligence that was in charge of penetrating large concentrations of Germans and transferring information. That didn’t prevent us from carrying out actions like bombing trains, railroads, telephone lines and anything that would disrupt the lives of Germans beyond the front line.

Did you continue drawing in the woods?

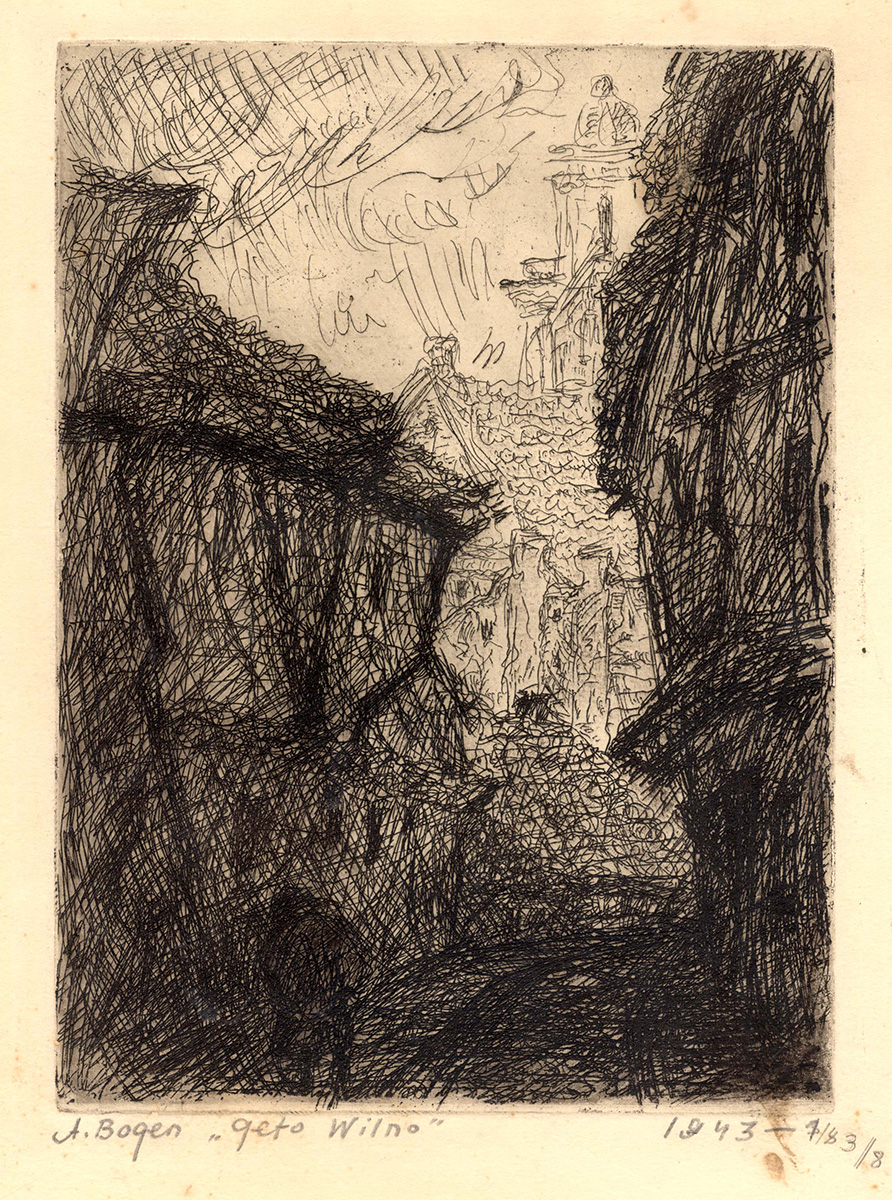

All the time, in impossible conditions, I had a pencil and some paper, and I drew. When we would get back from a mission and sit by the camp fire, drinking vodka and recounting the details of what happened, I would sit and draw the people, their experiences, and their clothes. I always had lots of drawings in my bag.

Do these drawings still exist?

We learned that the Germans are approaching with the intention of laying a siege to the whole forest. They brought ten divisions from the front with dogs and artillery and they combed the forest row by row. The partisans separated into small groups and managed somehow, many were also killed. Beforehand, when I learned that the Germans were intending to arrest partisans I took a tin box and put all my drawings in, and hid it under a pine tree. I marked the place to retrieve the drawings after the Germans were gone. Of course, I couldn’t find the tree.

The minute the Germans left the forest, the partisans regrouped and returned to their trenches. So I thought I'd get to the tree I marked. I got to the woods and I didn’t find the markings, the tree or anything.

I drew all these things on little pieces of paper, and after I was released I used lithography. I enlarged many things I drew from my experiences. In the woods back then, it was in the bag. There are many authentic things, what we actually did in the woods.

How did the other partisans react to you pulling out a sheet of paper and drawing?

With much respect, since all the Russian partisans wanted me to do a portrait of them. They were willing to pay for it with valuable objects. In Russia there is a lot of respect for art. During Stalin's era art was also important because it glorified the regime. There are drawings and paintings of Stalin. I also did a few "Stalins." I remember that on October Revolution Day, academy students used to paint huge "Stalins" and hang them all over the city. We did it as students, we wanted to make some money.

Do you see the drawings you created of the partisans while living in the woods, as art or as historical documentation?

I don't see it as art for art's sake. It's not like an artist sitting in his studio and thinking about composition and color and concept and message. This was a reaction to the facts that one faced; it was a spontaneous subconscious response. I didn’t feel or plan it. It's simply a reaction. Each person reacts to the horrors and to what happens, one with tears, one with a gun, and I reacted with a pencil in one hand and a gun in the other.

You say that it’s subconscious. How do you explain that urge to yourself? You say it’s documentation, but you call it a reaction.

I think it was after the war. During the war, I didn’t ask myself why I'm doing it, I had an internal compulsion. After the war, I thought that this reaction was like a spiritual armor to endure the hardship, on the one hand. On the other hand, I thought that maybe I wanted to expose the Nazi's atrocities to the "western world". I also thought it was something akin to biological survival. Everyone takes care of one’s offspring, so art is part of assuring one’s survival, one’s offspring's survival. I thought of all this after the war when I did a psychological analysis to answer the question, "what have you done?" Like Abba Kovner said, behind the story there was also a great artistic impression that's worthy in its own right.

But what compelled me to draw was reality. As far as I was concerned, there was no artistic thought, but a reaction to what happened in front of me. When you see something horrible you feel an electric current from your heart and you do this thing. You don’t plan it.

You didn’t immigrate to Israel immediately after the war, why did you eventually decide to come?

When I was in Lodz, in Poland, I felt great there. I was a known artist, the government commissioned my work. I had a large studio and a beautiful apartment and I was completely safe. But during the 50's a wave of Jews that had escaped to Asia returned to Poland. These Jews who escaped the war, now returned to Poland in the hope of getting to Israel. This wave was so influential that I couldn’t ignore it. I asked myself what I'll be doing in this jungle, in Israel. There it's green, it's cultural. Here on the way from Tel-Aviv to Jerusalem I saw these scorched places. What am I doing here? I painted only eastern people. Steadily, I made my way here and I was happy. I had a big house in Safed. I got closer to people, spaces, the Sea of Galilee, the market. In Safed I saw the Arab women, I also saw Jews there, for the first time I saw Jews from the Middle East. I was so excited that I went and drew them. It influenced me to see the all the Eastern types from Morocco, Tunisia. We were at the port entrance gate together. My wife, who came from great living conditions sat and cried, and I painted these types just like I did in the woods.

I acclimated, I painted here, I was happy about the blue skies of Israel. Only during the Eichmann Trial, the trauma hidden from an earlier period revealed itself. As a reaction I started painting ecological themes, also a form of destruction. So for a while I painted the ghetto, and destruction as well; the destruction of seas with petrochemical spills, Dollars covering the beautiful water with its dynamic life – it’s an ecological extermination. Slowly, I left it and returned to my signature Israeli painting. Lately, I do free-form art.

Finally, can you regard your self representation of yourself in Self Portrait?

Self Portrait – do you see facial features here? Actually, its half a swastika, behind it is a black patch which is the past, and that is the chronicle, and all together I call it an "auto-portrait," what I've been through.

In effect, this is a person who experienced the Holocaust. I am typical of those who experienced the Holocaust. Symbolically, I call it an auto-portrait because I experienced what thousands of others did. Styles change with circumstance and life. It’s all a reaction. When you are dealing with Modern Art, when you live in the present – I was in the woods and that was the reaction, I lived it. The authenticity is what an artist is measured by.