- Käthe Leichter, an inmate of Ravensbrück from her poem “An Meine Bruder” (to my brothers). The German original appears in Christa Schultz, (ed.) Der Wind weht weinend bei die Ebene: Ravensbrucker Gedichte, 1991, pp. 62–63. English translation from Rochelle Saidel, The Jewish women of Ravensbruck Concentration Camp, Madison, Wisc., 2004, p. 61.

- Saidel (2004), pp. 26-34.

- Ibid., p. 35; “Jehovah's Witnesses,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (no page numbers).

- Saidel (2004), pp. 37-40.

- Judith Buber-Agassi, Jewish Women Prisoners of Ravensbruck: Who Were They?, Oxford 2007, pp. 54-57.

- Ibid., p. 69.

- See below, the description of Olga Benario’s life.

- Ibid., pp. 228-231.

- Ibid., pp. 231–234. Idem, “Jewish Camp Families in Ravensbrück Concentration Camp” in Esther Herzog (ed.), Women and Families in the Holocaust, Netanya 2006, pp. 214–217 [Hebrew].

- Buber Agassi (2007), pp. 237-242.

- Lidia Vago (Rosenfeld)’s account; quoted by Buber Aggasi (2007), p. 241.

- Ibid. Compare to Rosi Mauskopf’s account also cited there. Rosi Mauskopf was left alone in Ravensbrück without any friends or family. “There was chaos in the Block. They fought over a slice of bread, in this hell they could not remain human beings. I experienced neither friendship nor solidarity.”

- Ibid., p. 242.

- Saidel (2004), p. 54. (Note this English edition mentions only four cookbooks; the later (2007) Hebrew edition (p. 45) revises this number to six, which is the figure used in the body text here.)

- Ibid., p. 56-57.. For a discussion of Qaustler’s diary see the online exhibition on Yad Vashem’s website.

- Ibid., p. 55. The excerpt is originally from “Rebecca's Legacy: A Ravensbruck Cookbook,” Zachor: Newsletter of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre 4, 1 (1988).

- See the online exhibition “Spots of Light: Being a Woman in the Holocaust”.

- Saidel (2004), pp. 42-44.

- Buber-Agassi (2007), p. 210.

- Ruth Werner, Olga Benario: A Historia de uma Mulher Corojosa, Sao Paulo 1987, p. 261.

- Fernanado Morias, Olga: Revolutionary and Martyr, New York 1990, pp. 241–242. Cited by Saidel (2004), p. 45.

- Ibid., pp. 45-48.

- Ibid., pp. 49, 62. Buber-Agassi (2004), p. 48-49.

- Saidel (2004), p. 62.

Oh, my brother, once there will be the day when no roll call will keep us!

Gates will be opened wide and the great, the free world will embrace us.

And then we concentration camp inmates will walk on wide streets.

But the others are waiting for us.

And whoever sees us, sees the deep lines written on our faces by the suffering,

Sees the signs of our mental and bodily torture, which will stay with us forever.

And whoever sees us will see the rage flashing bright from our eyes,

Sees the rejoicing in freedom deeply imbedded in our hearts.

And then we march in rows, the last, huge column of people,

And the road leads to light and sun.

Oh, brother, are you also imagining that day, you also must think:

The day will be here soon!

And then we march away from Ravensbrück, from Sachsenhausen, from Dachau, and Buchenwald1

During the Holocaust, Jewish women were sent to seven different concentration camps across Europe. One of the camps, Ravensbrück in Germany, was unique in that it only detained female prisoners. Besides providing a short historical overview of the camp, we will also discuss here some points related to the lives of the Jewish members of the camp’s population—focusing on the social connections they forged among themselves, and the cultural-artistic activities they engaged in to occupy their time.

Historical Overview of the Camp

Ravensbrück was established next to the eponymous village in north-eastern Germany, 90 kilometers north of Berlin. It lies on the banks of the Havel, near the picturesque Schwedtsee lake. The camp was opened in 1939 and was designated for the internment female political prisoners. The first contingent of inmates was transported from Lichtenburg camp with SS-Hauptsturmführer Max Kegal, who served as camp commander until 1942. After Kegal, SS-Hauptsturmführer Fritz Suhren served as camp commander until its liberation in 1945.

The camp was initially small: at the end of 1939 it had only 2,000 inmates and by the end of 1942, 11,000. As the war drew to a close the camp turned into a central transit station for prisoners from a variety of different populations. In 1944, more than 70,000 women would pass through the camp, most of them staying there for a relatively short amount of time. They were usually sent forward to one of Ravensbrück’s 34 sub-camps, some of which were quite far away. In 1944, the relatively permanent inmates of Ravensbrück numbered 26,700.

Medical experiments were conducted in the camp, mostly on Polish political prisoners and gypsies. At the end of March 1945, the camp began to be evacuated. Some 25,000 inmates (and inmates from nearby camps) were marched in the direction of Mecklenburg while thousands of German prisoners were released on the spot. When the Red Army reached the camp, on April 29–30, a mere week before Germany’s unconditional surrender, the camp was populated by some 3,500 sick inmates who had been left behind.

- 1. קתה לייכטר, אסירת רוונסבריק, מתוך השיר An meine Bruder (לאחיי); המקור הגרמני מופיע אצל Christa Schultz (ed.), Der Wind weht weinend bei die Ebene: Ravensbrucker Gedichte, 1991, pp. 62-63 . התרגום לעברית אצל רושל ג' סיידל, הנשים היהודיות במחנה הריכוז רוונסבריק, (מתרגם: אברי פישר), עכו תשס"ח, עמ' 50.

Groups of inmates in the camp

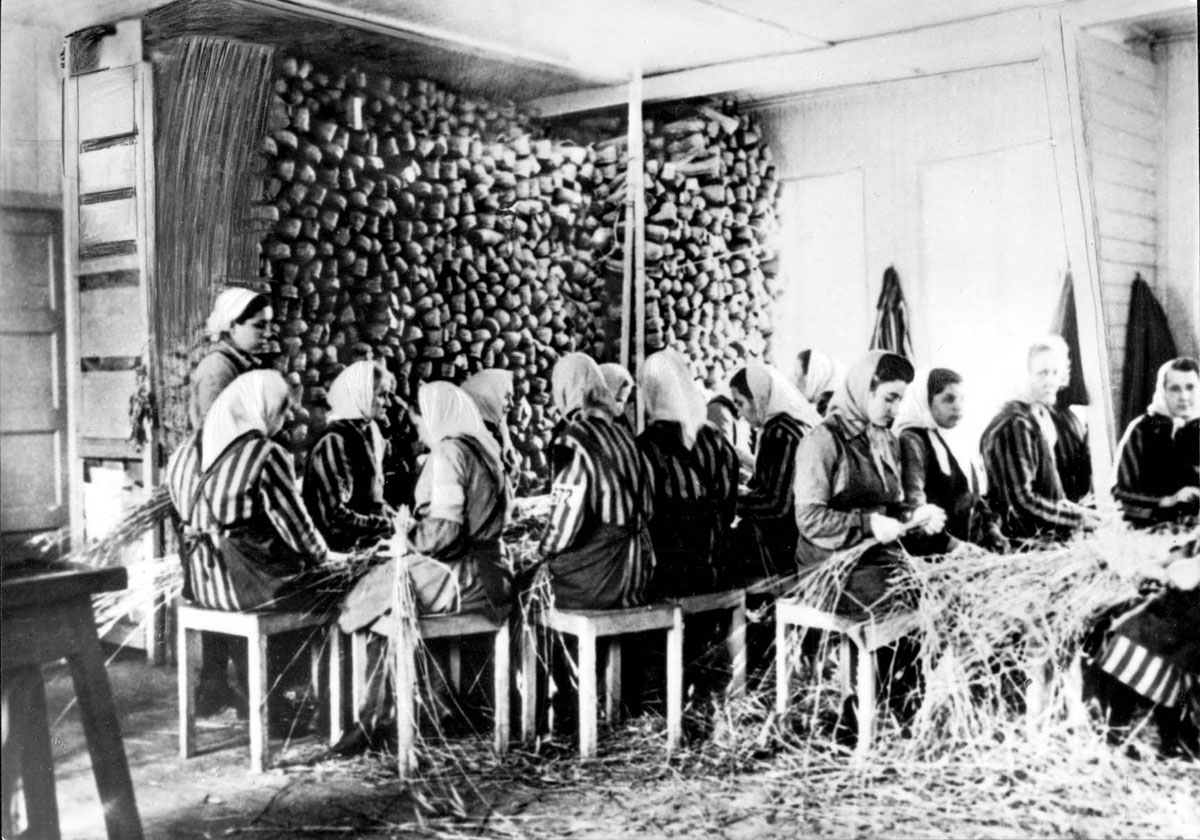

As mentioned, Ravensbrück did not just detain Jewish women. In fact, Jews always comprised a minority of the camp’s total population. Over the years, women from forty different countries would pass through the camp. They were sorted into separate groups based on the grounds for their arrest, and members of different groups could be distinguished by the colored cloth triangle they wore. The largest group in the camp was comprised of political prisoners who wore a red triangle. These women belonged to a variety of ethnic, religious and social affiliations. They had all been charged with illegal political activity such as membership in a communist or other illegal political party, providing intelligence or aid to regime’s enemies, or engaging in illegal resistance activities. Among these political prisoners, Germans, Poles and Frenchwomen were prominent. Towards the end of the war, women from the USSR were also detained there (these were POW’s from the Red Army who after a certain point were classified as political prisoners and sent to Ravensbrück).2

The second group of inmates were German religious prisoners—primarily Jehova’s Witnesses and members of other Christian denominations. These inmates had, in keeping with their faith, refused to cooperate with the Nazi regime (for example, refusing to heil Hitler). Although they could have easily denied their beliefs and been released without a scratch, most of them refused to do so.3These prisoners wore a purple triangle. The third group, marked by their black triangle, were those who ascribed to what the Nazi regime defined as “asocial” views. This group was also diverse and included women whose sexual behavior did not conform with the values of the regime, such as, prostitutes. Lesbians, who were also defined as “asocial,” should also be mentioned in this context (as opposed to male homosexuals who had their own category and usually wore a pink triangle in the various concentration camps). Gypsies, due to the prevailing view about their social lives and nomadism, were classified as part of this group as well. In addition to the aforementioned, there was a group of criminal prisoners—who wore a green triangle, and, of course, Jewish prisoners who wore a yellow triangle.4

The concentration camp in Ravensbrück was designated for the internment of political prisoners and other elements hostile to the Nazi regime. Why, then, were Jewish women detained there as well? Were they also political prisoners? To answer this question, it is important to distinguish between two different periods of the camp’s activities. At first, Jewish inmates were—at least formally—accused of political transgressions, race crimes (sexual relations with an Aryan), asocial behavior, or illegal border crossing. They were also charged with different sentences such as administrative detention, temporary detention, deportation or “re-education.” It seems, however, that these definitions were not precise and were relatively arbitrary. Many of the Jewish prisoners detained for political reasons, had not engaged in any real illegal activity. Likewise, it was common for a Jewish inmate to be classified as a race traitor with little documentation or proof. Finally, it should be added, that many were detained without any specific charges.

In August 1942, the Germans began to evacuate Jewish inmates from Ravensbrück, rendering the camp Judenrein, and sending them to Auschwitz. Even during the next period of the camp’s management, lasting until February 1943, when about five hundred new Jewish prisoners arrived at the camp, most Jews continued to be classified as political prisoners. It is, however, highly doubtful, that this generic charge had any grounds.6

As mentioned, after the Jewish prisoners were sent to Auschwitz in the summer of 1942, the stream of Jewish prisoners arriving at the camp was heavily reduced. However, beginning in August 1944—a period characterized by dramatic steps taken by the Nazi regime in light of the war’s imminent end and their impending loss—much larger groups of Jews were sent to the camp. Some of these were survivors of the ghettoes of Poland, others former inmates of Auschwitz, and some sent straight from Budapest without stopping at any other camp. At this point it was clear, that these prisoners were being detained for their Jewishness and nothing else, and they were sent to the camp as laborers. These inmates, were thus no different than any other Jews in German occupied Europe. From August 1944, until the camp’s liberation, more than 14,000 Jewish women were sent to the camp, in stark contrast to the mere 2,000 who had been interned there previously.

Throughout the camp’s history, even at the very beginning of its operation, the SS treated Jewish inmates as a separate group. Besides their distinct yellow triangle (which when combined with another triangle, the red for example, created a Star of David), they were almost always consigned to separate barracks from the other inmates. Likewise, they worked in separate groups, and were forbidden from having any real contact with non-Jewish inmates.

Relationships and Social Organization

An interesting characteristic of the lives of the Ravensbrück inmates is what Judith Buber-Agassi has referred to as “camp families”—small social groups comprised of a few inmates who joined together as an imaginary “family.”

In her study on the Jewish inmates of Ravensbrück, Buber-Agassi dedicates a chapter to the social ties established among inmates, discussing the nature of these relationships and how they were forged. Here also it is important to differentiate between different periods within the camp’s history, which changed according to the character of the Jewish population and its relative size to other groups. In one period when the Jewish inmates numbered 600 and all lived in the same block, a certain level of shared cultural-educational activity was established.7 This was, however, generally not the case and it is usually difficult to find substantial testimony of comprehensive social organization among the camp’s Jewish inmates. Accounts instead point to a relatively large number of very small social groups and organizations. While several reasons may lie behind this phenomenon it can be generally be attributed to the near impossibility of establishing any kind of comprehensive social organization in such a heavily disciplined camp. Nevertheless, and perhaps surprisingly, other groups of prisoners did succeed in creating relatively efficient and comprehensive forms of social organization. This was the case for German-communist inmates, Polish political prisoners (who created an efficient and impressive social apparatus) or the members of the Catholic resistance group. The phenomenon was, however, rare among the Jews.8

In many senses, the Jewish inmates of Ravensbrück—like Jews in many other camps—had relatively little in common: they did not share a common homeland or language, they lacked a strong, well-developed ideology to turn them into a united group, and unlike German communists, for example, they had not been detained for any clear ideological reason. As mentioned, even if many of the first Jewish inmates were formally charged with a specific crime, the reason for their internment was generally far simpler—they were Jews. And while many of the Jewish inmates hailed from religious families or at least from families in which religion played an important role, this proved insufficient for unifying the Jewish prisoners hailing from different backgrounds.9

- 2. סיידל (תשס"ח), עמ' 21-26.

- 3. שם, עמ' 28; " Jehovah's Witnesses", United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- 4. סיידל (תשס"ח), עמ' 30-32.

- 6. שם, עמ' 62.

- 7. ראה בהמשך בתיאור קורותיה של אולגה בנריו.

- 8. שם, עמ' 206-208.

- 9. שם, 208-210; הנ"ל, 'משפחות המחנה של האסירות היהודיות במחנה הריכוז רוונסבריק', אסתר הרצוג (עורכת), נשים ומשפחה בשואה, נתניה 2006, עמ' 95-112.

It appears, however, that the role of very limited social circles —consisting of only a handful of prisoners who considered themselves a family—was of paramount importance. Quite often these were relatives, sisters or cousins. But sometimes this was a “surrogate family” such as groups formed by inmates who had lived in the same city or ghetto, or in some cases a relationship between two good friends. An interesting phenomenon is the practice of older women “adopting” teenagers who had been separated from their families or lost their mothers. For example, Erika Kounio Amariglio’s mother—who hailed from Salonika and took part in a death march to Ravensbrück with her daughter—adopted another three Greek girls. These five women created a “camp family,” which remained united throughout the death march to Ravensbrück, in the camp itself, afterwards in the sub-camp Malchow and during the march from Malchow until liberation.10

[L]onely women were a rarity in the camp, because being alone meant near certain death. Everyone without a close relative, or a good friend, had to have a Lagerschwester (camp sister), or the younger girls whose mothers had been gassed, were adopted by mature women.11

Seren Tuvel Bernstein’s account demonstrates how important it was to preserve these social circles:

A great cry went out, a moan that welled up from the bottom of despair. Each pair would be cut in two, leaving every woman far less than half of what she had been in a pair. Having a sister, a cousin, or a friend in the camp with you was sometimes the only thing that gave you the courage to go on; each lived solely for the other.12

According to Buber-Agassi, each “camp family” naturally had one member who stood out as a leader of sorts, someone with authority and responsibility. As Bernstein described it:

I felt completely responsible for these three young girls; to me we were all sisters. I had to do everything in my power to enable us to remain alive. Survival became a matter of establishing rules and adhering to them religiously. I was the oldest; I made the rules.13

Cultural and Artistic Activities

Resistance and disobedience were not real possibilities in Ravensbrück—at least not for the Jewish inmates. But despite the almost unbearable conditions, the inmates did their best to maintain a normal life-style filled with a certain amount of cultural activity. An interesting phenomenon was women who would try to recall recipes, discussing them with others and committing them to writing—obviously without being able to every cook any of them. This imaginary space allowed them to remember their former homes and world; it was a safe space impervious to German intrusion. At least five of these cookbooks were written by Jewish inmates in Ravensbrück.14

Františka Quastler (later Nurit Stern) from Bratislava, Slovakia, arrived in Ravensbrück at the end of 1944, when she was 13. She wrote the following recipe:

English cookies. Beat four egg whites with 12 dekagrams (units of 10 grams) sugar for a long time. Add 12 dekagrams almonds (not blanched), and 12 dekagrams flour. Bake in an oblong pan. Slice thinly the following day.

She wrote this recipe in a diary, made out of pieces of paper stolen from the factory and then sewed together with wire. The booklet contains dedications written by camp inmates and recipes that she wrote herself. Nurit relates that the women would “cook” with their imaginations.15

- 10. בובר אגסי (תשס"ח), עמ' 214-217.

- 11. עדותה של לידה ואגו (רוזנפלד), הובאה אצל בובר אגסי, עמ' 215.

- 12. שם. אך השוו לדבריה של של רוזי מאוזקופף, שנותרה ברוונסבריק לבדה ללא משפחה או חברות: "שרר תוהו ובוהו בבלוק. הן רבו על פרוסת לחם, בגיהינום הזה הן לא יכלו להישאר אנושיות. לא חוויתי כל חברות או סולידריות" (דבריה הובאו שם).

- 13. שם, עמ' 2127.

- 14. סיידל (תשס"ח), עמ' 45.

- 15. שם, עמ' 46; אודות ספר הזכרונות של קווסטלר ראה בתערוכה המקוונת באתר יד ושם: https://www.yadvashem.org/yv/he/exhibitions/albums/quastler.asp .

Another cookbook was written by Rebecca (Becky) Teielbaum who resided in Ravensbrück from November 1943 until the camp’s liberation. Greenberg , a resident of Brussels, was sent to the camp for privy duty, but was later moved to work in the Seimen’s factory. From there she was able to steal some paper, which Rebecca used to create her recipe booklet:

Exhausted, cold and hungry they [the women of the barrack] would talk endlessly about the food they longed for, about family meals they had shared and the dishes they planned to make if they survived the war [...] Each woman in turn would share recipes in a paradoxical effort to stave off hunger. It seems as though these oft-repeated recipes and stories about family meals served as a talisman sustaining their humanity and hope in a time with little hope. Rebecca hid away small pieces of paper and an indigo pencil and set about recording these recipes [...] In her clear, measured and even script, Rebecca filled 110 pages. The pages are meticulously hand stitched as a little volume that can rest comfortably in the palm of one’s hand [...] The recipes themselves are quite extraordinary and elaborate [...] Upon the book’s completion each of the women would take turns reading from its pages: mouss au chocolat, gelee de groseilles, gauteau-neige, plat hongrois, oeuf hollandais, sabayon italien,souffle a la confiture.16

Another famous example is Yehudit Aufrichtig. Born in 1914 in Hungary, she immigrated to Amsterdam in 1938. After the Nazi conquest of the Netherlands, she began to take part in covert activities and giving food to Jewish families hiding in the countryside. After being caught in 1944 she was sent to Ravensbrück. She and her friends also found temporary entertainment and comfort in the writing of “fantasy recipes.” This is what one of her fellow inmates wrote her one day when she was too ill to receive her daily food distribution:

To allow you to get at least some mental pleasure from our meals, I’ll give you the details of the menu. Breakfast: Karlsbad-style breakfast—eggs, butter, cheese, jam. Brunch: At 10:00 we had yogurt, langus [a deep-fried yeast pastry], and a radish. Lunch: potato soup with sour cream and laurel leaves, asparagus in sour cream and bread crumbs. Sunny-side-up egg and beef in tomato sauce with macaroni. Fried apple in vanilla sauce. Afternoon: chocolate milk with whipped cream and egg bread with almonds and a “hornet’s nest” [a type of cake]. Supper: marrow, fried potatoes with onion, salad with green onion, little cookies and black coffee, fruit. We gorged ourselves with Klari. We ate everything apart from a little slice of bread, which we saved for you17

Another exciting chapter in the history of the Jewish women of Ravensbrück is the story of two relatively well-known socialist activists who were interned in the camp and made a significant contribution to the social leisure of the Jewish prisoners during the camp’s first period of activity. These two women were Olga Benario–Prestes and Käthe Pick Leichter.

Benario’s life story was far from normal. Born in Munich to a Jewish upper-middle class family, she became a enthusiastic communist activist in her youth. At age 18, she was arrested for a short time and afterwards fled to Moscow where she was elected to the congress of the Communist Youth International and later to the leadership of the Comintern. In 1934, she accompanied Brazilian communist leader, Luís Carlos Prestes, on his trip to Brazil, developing a romantic relationship with him. Prestes sought to take control of the Brazilian government in a coup, and as an act of retribution the Brazilian government seized Olga—who was pregnant at the time—and handed her over to Nazi Germany. Olga was sent to various jails and concentration camps, sometimes being subjected to interrogation and torture. She managed to conceal the whereabouts of her daughter Anita, who was born in 1937 (Anita’s family managed to smuggle her back to her father in Brazil). Olga was in the first contingent of prisoners that arrived in Ravensbrück from Lichtenbrug, and was appointed Blockalteste (block leader).18 Besides wearing the red triangle of political prisoners (and according to some accounts, she also “earned” a black triangle for asocial prisoners) Olga was obviously identified as a Jew as well and for a significant period of time, between 1940 and 1941, the 600 Jewish inmates of Ravensbrück all resided in her block.19 Olga Benario gave exercise lessons every morning, attended by all the prisoners, while also secretly organizing lessons in Russian and French as well as book readings in the evening. For example, one prisoner recalls that a prisoner found in a pile of rubbish a moldy copy of Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Olga began to read it together with a small group of inmates.20 One of Olga’s most impressive achievements was the creation of a detailed and precise atlas to help teach her fellow inmates geography, helping them understand the different arenas of the ongoing war. The atlas can be found today in the camp archive.

Rochelle Saidel who collected stories from many of Ravensbrück’s inmates cites in her book Olga’s last letter to the daughter she would never see:

It is utterly impossible for me to imagine, my dear daughter, that I will never see you again, never squeeze you in my eager arms. I wanted so to be able to comb your hair, to braid your braids […] I promise you now, as I say farewell, that until the last instant I will give you no reason to be ashamed of me.21

- 16. שם, עמ' 44-45. התיאור המצוטט מקורו במאמר "Rebecca's Legacy: A Ravensbruck Cookbook", Zachor: Newsletter of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, 1, 4 (1988) .

- 17. ראה בתערוכה המקוונת "כתמים של אור: להיות אישה בשואה": https://www.yadvashem.org/yv/he/exhibitions/spots_of_light/yehudit_aufrichtig.asp.

- 18. סיידל (תשס"ח), עמ' 34-35.

- 19. בובר אגסי (תשע"ב), עמ' 210.

- 20. Ruth Werner, Olga Benario: A Historia de uma Mulher Corojosa, Sao Paulo 1987, p. 261.

- 21. Fernanado Morias, Olga: Revolutionary and Martyr, New York 1990, pp. 241-242. הדברים מובאים כאמור אצל סיידל (תשס"ח), עמ' 36.

Františka Quastler’s album from the Ravensbrück camp (the letters of FKL stand for Frauenkonzentrationslager, “Women’s Concentration Camp”)

Käthe Leichter was older than Olga Benario. She was born in Vienna in 1895 to the wealthy, well-known, Jewish family Pick. Like Olga Benario, she too was drawn into socialist activism. She was the student of esteemed sociologist Max Weber, finished her doctoral studies in the social sciences in the University of Heidelberg with honors, and later filled a number of key roles in the leadership of socialist parties in Austria. Immediately after the Anschluss her husband, Otto Leichter, who was also an important activist, fled to Czechoslovakia. Käthe made every preparation to join him but on the day of her planned escape, she was arrested. In 1939, she was charged with illegal political activity and in 1940 sent to Ravensbrück.22

Käthe was a prolific writer, and shared her plays and poems with her fellow inmates. A group of prisoners even produced and performed one of Käthe’s plays entitled “Schumm-Schumm.” The play delivered an unequivocally anti-Nazi message; “it contained many songs mocking the SS and biting social criticism” as attested to by Rosa Jochmann. Jochmann also recounted that Käthe destroyed the original play and replaced it with a different version in which it is the Jews who are derided, and the SS officers praised. It was this version which the SS officers found among Käthe’s posessions, thus saving the actors and spectators from immediate execution, allowing them to get off with “only” a few weeks in the punishment block.23 In the long term, however, all those who participated in the play were sent on the next transport to the gas chambers. This was also the tragic end which met both Olga and Käthe—both were sent in 1942 to the gas chambers of the Bernberg Euthanasia Center. They were murdered with the majority of Jewish prisoners of Ravensbrück at that time.24

Summary

We have reviewed here certain aspects of the lives of the Jewish prisoners in Ravensbrück. To what extent are the characteristics discussed here unique to female prisoners? Was the significant tendency of the female prisoners to band together in small groups related to their gender? Was imaginary escapism and spiritual healing and refuge in the form of discussing recipes from their mothers’ homes a unique phenomenon? Or was it no different, in principle, from a group of male prisoners trying to remember, between roll call and labor, stories from their former towns and universities? We will not provide any definitive answers to these or any other questions here. They will instead be left open to the reader’s consideration.