- There were also approximately 5,000 Sinti and Roma who had been imprisoned in the ghetto and met the same fate.

- B. [Bernard] O. [Ostrowski], ]Lodz Ghetto Chronicle, vol. 2 (1942), pp. 137-138.

- Not to be confused with the "Oneg Shabbat" Archive in Warsaw. This information comes from Ruth (Berlińska) Eldar, To Shake the Temple Pillars, https://www.lodz-ghetto.com/glazer_factory.html,23 accessed September 30, 2014.

- Ibid.

- Josef Zelkowicz, In Those Terrible Days (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2002), pp. 186-188.

- Sara Zyskind, Stolen Years, (Minneapolis: Lerner Publications Company, 1981), pp. 47-48.

- Ibid., pp. 48-49.

- In Those Terrible Days, p. 16, introduction by Michal Unger, quoting Yeshayahu Szpigel, a Yiddish author.

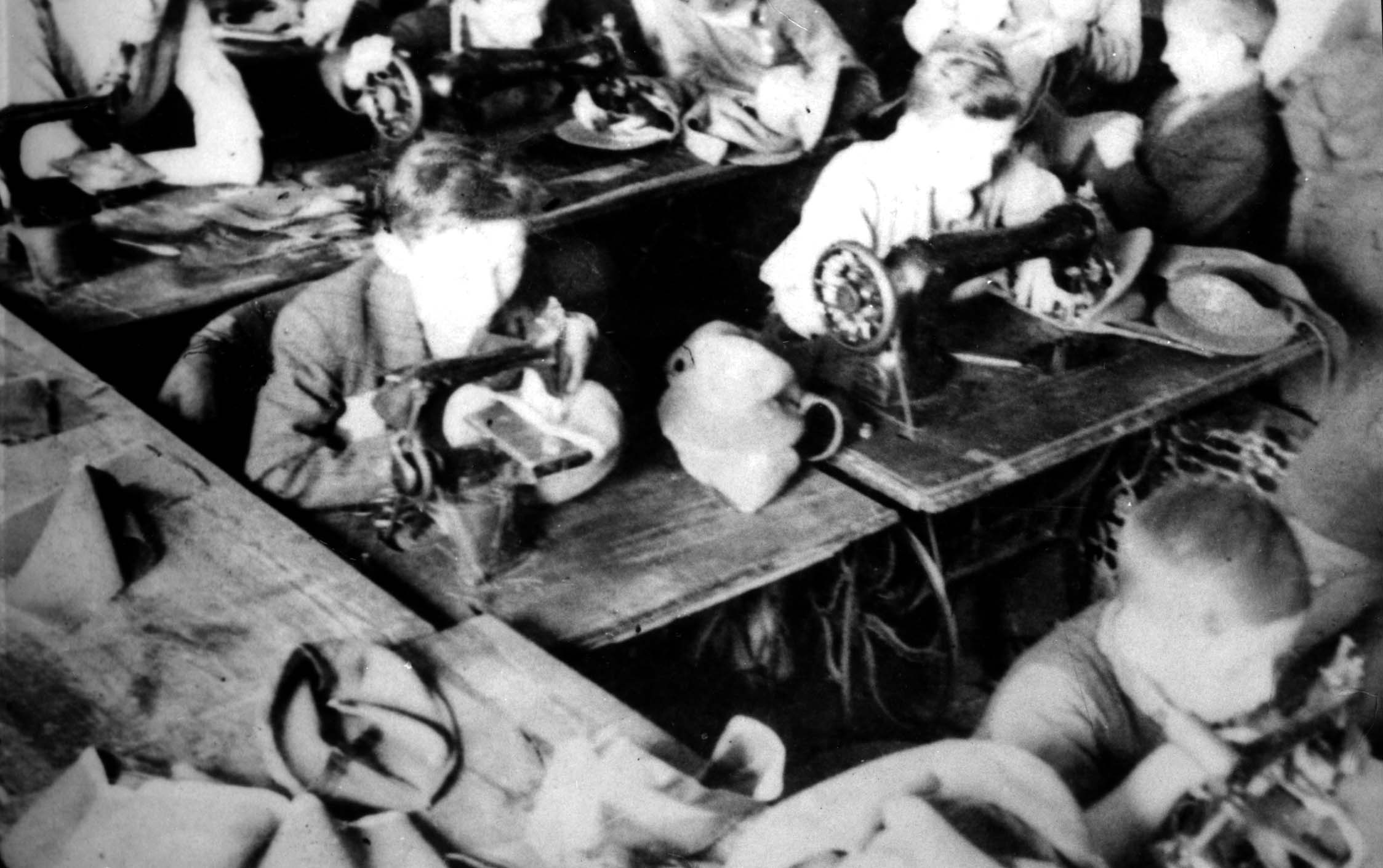

It was the beginning of 1942. In the Lodz ghetto, thousands of Jews1 were spirited off to the unknown on trains. The unknown turned out to be Chelmno, the very first death camp, where 55,000 Jews of the ghetto were murdered between January and May, 1942. Many of the deported Jews were young children and the elderly, those who did not work and consequently were considered "unproductive" by the Germans. In the ghetto, Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, the head of the Jewish leadership, believed that the only way to keep the Jews of the ghetto alive was to open factories and workshops in order to make the ghetto "productive." The ghetto was transformed into a labor camp. In its factories, some children who were over ten years old and could work were taken in and given jobs in order to protect them from deportation. Rumkowski even ordered the ghetto enterprises to set aside 10% of the jobs in each of their workforces for children and teenagers, in order to save as many as possible. Despite this, conditions in the factories were difficult – they were crowded and congested, lighting and ventilation was poor, and hours were very long, especially for children, and especially if these children had to wake up early to walk to their jobs.

- 1. 1

One of the factories that employed children was the tailors' workshop. When we discuss the "chaos" of the Holocaust and the fact that the normal world was turned on its head, the fact that children were employed in a tailors' workshop in the Lodz ghetto is just another expression of this. In a normal world, children are told by their parents to stay away from scissors, from needles, from other sharp and dangerous objects that could hurt them. In the Lodz ghetto, not only did children have to work in order to stay alive, which was already a reversal of the normal order of things, but children had to work with dangerous objects that in a normal world they would never be allowed to touch.

At the tailors' workshop, vocational courses were set up in a setting known as "szkolka", Polish for "little school." Children were trained not only in their vocation, in courses including machine sewing, hand sewing, cutting and drafting, but were also taught some general studies, including bookkeeping, hygiene and even Yiddish. The Lodz Ghetto Chronicle reported:

"At the beginning of the month, they opened vocational courses in the tailors' workshop building where youngsters might acquire tailoring skills. The establishment of this institution effectively solved the problem of training children and teenagers in tailoring, a basic trade in the ghetto. Nearly 2,000 children are studying this trade, and all the tailors' workshops are involved. Each such workshop and similar enterprises…send the most talented children to these courses." 2

The workshop, which produced undergarments and dresses, was run by Leon Glazer. Glazer was sympathetic to the children he supervised. He gave them moral support as well as material support. Most importantly, he allowed children as young as nine years old to participate in the labor performed by the factory and to take vocational courses that the workshop offered, thus saving their lives - if only temporarily.

- 2. 2

During this period of great uncertainty and terror, as cattlecars with "unproductive" Jews sped to Chelmno, artists and poets in Glazer's tailors' workshop produced an exceptional children's fairytale accompanied by beautifully-drawn pictures. They did not sign their work, nor did they leave us any clues as to how to interpret the tale and the pictures. The work was found after the war in the ruins of the ghetto. It is now known as the "Legend of the Lodz Ghetto Children." It is an extraordinary work that can be interpreted on a number of levels, as many fairytales can. In this fairytale, however, there is no "happily ever after."

Reading the words alone, there is a level that can be understood by children, and can be seen as trying to give the children in the ghetto and in the workshop a modicum of hope. The Legend speaks of a "prince in a wondrous land" (probably Glazer himself), who "throws a great bridge over the water and extends his hand to the children, joy bursting from his eyes." There is a "good, generous king" (probably Rumkowski) who "will not let us down." The Legend seeks to encourage the children to work and to sew. At the same time, its message to these children is not to be afraid.

Simultaneously, however, the fable could be understood by its adult readers in 1942 as a veiled expression of fear, bitterness and uncertainty - feelings that were best left unexpressed openly. The legend is populated by "a sickening dragon, a loathsome, disgusting form," and by a "giant, venomous snake [who] lurks cunningly" (probably the Nazis). It takes place in "fateful days and hard times [with] new worries and new hardships," where disconsolate boys ask, "Will the world be this way forever?" In the Lodz ghetto in 1942, where 55,000 people had been whisked away into the unknown and never heard from again, there was certainly reason to ask a question like this. There is a "pitched battle with a monster," and a "mighty wall" that is "unimaginably high and thick." Other characters in the legend walk along, "dejected[,] all of them with impotence in their eyes." All of these are expressions of the helplessness felt by the ghetto inhabitants imprisoned behind walls and fences in one small area of Lodz that they were powerless to leave.

We see from the text alone that the Legend has a very mixed message. Yet, the pictures add a deeper dimension to the poetry of the Legend. The terror of the time, and the tragedies experienced by the Jews in the ghetto, are given voice by the barrenness and desolation evident in some of the scenes, and by symbols used repeatedly. A menacing sun is colored not yellow, but red – the color of blood, the color of danger. A mysterious hand seems to wave hello but could more probably (considering the deportations) be waving goodbye. A fence fails to protect those within it because it is broken and crooked. Other tricks of spatial perspective imply something profound about the chaos and confusion of those times. Although the pictures are naïve and well-suited to a children's fairytale, they cause a visceral sense of discomfort and disquiet in the viewer.

The Legend – both in its poetry and in its drawings – is all the more exceptional when we consider that the people who created it did so amidst the horror that surrounded them. Why? In creating this work, the poets and artists behind it not only conveyed to us a sense of their desperation and terror, but created an eloquent testimony, both written and artistic, that remains for posterity a symbol of the fears and the hardships faced by the ghetto, and especially by the children of the ghetto, in their struggle to survive.

The Legend consists of 17 drawings and text that accompanies each drawing. A kit containing the entire legend, 17 posters, and a Teacher's Handbook with historical background, can be purchased on the Yad Vashem website. The Legend can be used to teach the story of the Lodz ghetto in a high school classroom setting. Three examples are below.

I. The Vocational School

This is the second painting in the Legend. In it we can see sewing machines, patterns cut for dresses, and the word "Szkolka". They represent the vocational school opened in Glazer's tailors' workshop. Beneath this, we see the prince with what is probably Glazer's face from a photo, and two little girls with worried looks on their faces. The text that accompanies this picture follows:

"Under a heavy burden bends the boy:

'Will the world be this way forever?'

The prince's heart contracts in pain

At the sight of the boy's sad face,

When amid the silence of the palace

The crowing of a rooster erupts

And the regal yearnings wander afar."

If Leon Glazer is the prince in the Legend, we see here how the suffering of the children who worked in his workshop pained him. To alleviate the children's suffering slightly, he did what he could to support them with extra food and uplifting activities. Ruth Eldar recalls:

"... What I remember best was our literature and drama circle, in which I enthusiastically participated. There were eleven of us, all from the Wasche und Kleider Abteilung and from the dress-making school. We had our lecturers and our newsletter, created illustrations and posters and theater performances. Leon Glazer, the manager of our department, pleaded at Rumkowski's to authorize and support this activity of ours. The meetings were held on Saturdays after dinner.[…] It was a great distinction for the eleven of us. At every meeting we would even receive a loaf of bread and a big piece of sausage. We called those Saturday meetings in Hebrew Oneg Shabbat (Shabbat joy)." 3

Yet we also understand that when the boy in the fable asks whether the world will be this way forever, he is talking about the difficulty of the work in the sewing workshop.

"…We had been making the same kind of dress in the piecework system, on a production line, for two years. Our group was supervised by Mrs. Kujawska. She could forgive a lot and even make corrections where necessary. Mr. Widawski, a specialist on laces and collars, made our work easier. The rhythmic rattle of the sewing machines, the steam of the ironed dresses, the hanging fabrics and the fear of an unfilled production plan were hovering over our heads like ghosts. But the Germans did not manage to snatch everything from us even in that atmosphere of misery, starvation and cold. They could take our piece of bread, a bowl of soup, but they could not deprive us of our dreams and childhood imagination. Full of brave plans and imaginations, we were building in our visions a new kingdom. A kingdom reaching the sky, a kingdom of the promised land, where there was neither starvation, nor the Girl with Matches, nor little Jasio, who did not live to see the spring." 4

If using the Legend in the classroom, we could ask what type of information about the situation of children in the ghetto we can glean from the text. What does the picture tell us that illustrates this information?

The terrible difficulties of ghetto life for the children can be understood from other sources as well, including Josef Zelkowicz. Zelkowicz was a writer who served as director of the ghetto archives, kept a 27-book diary found after the war, and contributed to the ghetto Chronicle. He wrote:

"Do you have children in the ghetto at all? That species is heading for extinction even before it can develop into a creature called a child. If the child has the good fortune of not dying at once, he immediately becomes a full-fledged grownup. In the ghetto there are no children but small Jews. Until the age of ten, they do not work but queue at the kitchens for bread. The small Jews are at work at the age of ten and thereafter. They have neither beards nor wives, but they are already working. […] The ghetto children must work. They are paid 10 pfennings per hour, 80 pfennings a day. It's too little, not worth a thing, and the labor is too difficult for them.

Difficult, if only because this small Jew is confined for eight hours inside a factory or a ressort where, for the most part, conditions contrary to the basics of hygiene prevail.

Difficult, if only because this small Jew, not given a chance to grow, bears the burden of reporting to work like a disciplined soldier, at 7:00 a.m. on the button. For any delay, 50 pfennigs are deducted from his "wage." To report to work at 7:00, this small Jew has to wake up at 6:00. And every extra hour that this small Jew is awake means another hour of hunger pangs during the long day. […] The ghetto children must work. If they do not, they are at risk of being torn from their parents and sent to an unknown destination. When they work, they are useful, protected ghetto citizens, aged eleven, twelve and thirteen. […]

The machine ingests their young tender bodies, squeezes them, and turns them into waste. It is making of them what it has made of their parents… If their legs do not yet bulge from hunger – after all, they need not carry a body as heavy as the one their parents' legs must bear, they nevertheless have twisted, stooped spines, sunken chests, and subdued, dejected eyes that give off a distant, alien, cold gaze like today's sky…"5

II. The Children's Fate Depends on Their Ability to Work

Another of the paintings paired with verse similarly discusses the anguish of the children who may not know how to sew but understand too well that their fate depends on it.

"Sweat pours off the girl's brow

She looks for help – it's no use, she's on her own.

It's because of the pranks and tricks of the naughty demons and dwarfs

Perpetrated crudely and malevolently

Always ruining her stitches."

What do we take from this text? What can we surmise about the children in the ghetto workshops?

We must always remember the age of the children in the workshops. They were very young and inexperienced, and in many cases did not know how to perform the work they were required to do. Sara Zyskind survived the Lodz ghetto as a young teenager. Her story bears this out.

"It was not long before I joined […] the ghetto work force. Uncle Abraham got me a job in his workshop, which manufactured brassieres and corsets for German women. His eyes shone with happiness as he described to me how he had managed it. He had simply gone up to the supervisor and told her about his eighteen-year-old niece who had worked in a bra and corset factory before the war.

'But Uncle, I'm only fourteen!'

'Don’t interrupt!' he said sharply. […]

'But I haven't the slightest idea how to make such things,' I protested, shaking all over. 'I've never even touched a sewing machine before! They're sure to find me out!' […]

'You have to lie, my child,' Aunt Hanushka interceded quietly. 'And you'll do it convincingly. After all, it won't harm anybody. Having a job is the only thing that's likely to save you and perhaps enable you to see the war through. You need the extra ration of food. And you know that the jobless are constantly being deported. [...] No one has a clue where they've gone to.'" 6

On the day she was to report to work, Sara's aunt styled her hair to make her look older. Her uncle explained how easy it was to operate a sewing machine. Sara reported to the supervisor at the workshop, who showed her how to stitch two pieces of material together in a straight line, and told her to finish the batch of pieces before her. Sara writes,

"I began to work, pairing the two pieces as I'd been instructed, setting the wheel in motion, and pushing the treadle up and down. Wonder of wonders! The machine started turning. It purred pleasantly, and the pieces of material moved forward. I reached out for the next pair and the next. A thrill of happiness ran through me. Uncle Abraham was right. I could handle a sewing machine without a hitch. […]

But what was this? No sooner had I moved the completed batch aside than all the pieces fell apart as though they'd never been stitched together. I was baffled, for the machine had been running without a snag. [….] My happiness had been premature. I found out later that while Uncle Abraham had told me about the wheel and the treadle, he had neglected to mention that the sewing machine also needed to be threaded!

Just then the supervisor passed by. She came to a sudden halt on seeing the mess I'd made of my assignment. I stood up.

'Listen,' I said, feeling the hot blood rush into my face, 'I can't do it. I don't know anything about this work. I've never touched a sewing machine in my life!'

I was trying hard to keep my composure, but despite desperate efforts, I burst into tears. 'I told you a lie,' I sobbed, 'but I'm not a liar, and I didn't mean to cheat you. It's work and bread I want.'"7

Sara had good luck – her supervisor was a gentle woman who let her stay on and ultimately taught her how to sew. But the Legend and the face of the little girl at her sewing machine, whose work is ruined by "demons and dwarfs", clearly expresses the frustration of the small children who were forced by circumstances too grow up too fast and to be responsible for work they didn't necessarily know how to do. The children of the ghetto may not have known how to express their fears – or they may have repressed them. The demons and dwarves allowed the children reading the Legend to project their undesired, unexpressed and unacceptable feelings onto these pretend creatures.

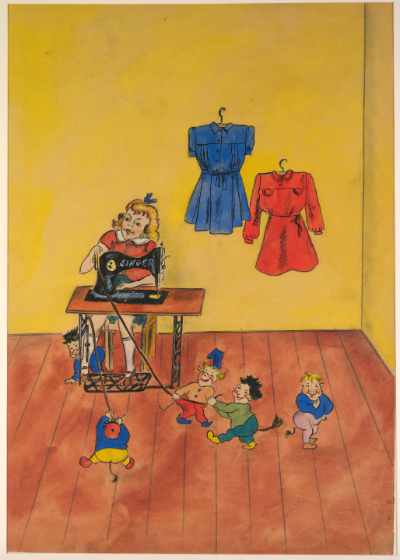

III. Happily Ever After

"Hey, the obstacles are gone!

No more worry.

Now the heart pounds with joy.

In the spacious hall

The toil, the strain are forgotten – for now.

The cutters leap to the children's side

Straight from the wall, and the little laborer-girls

All jump, set down their burden, and

Leave the room dancing with glee."

The tone of this text is completely different. What is it telling us? What were the authors of the Legend trying to show with this optimistic message?

Again, the text can be seen on two levels. For the children of the ghetto, it is unadulterated optimism. The little girl has by now learned to sew. The expression on her face is one of happiness. She is a worker, she has learned, she has progressed. For the children, this is a positive message of encouragement. They, too, can learn how to work and can be successful.

For the adults, though, two small words give away the danger that lurks behind this exaggerated joyfulness: the toil and the strain are forgotten, "for now." Those two words have a decidedly ominous ring. This is the mixed message of the Legend, and this is what makes it so effective in portraying the reality of the Lodz ghetto. What may have seemed like "happily ever after" is possibly only a temporary reprieve. And indeed, most of the children (and the adults) who were saved from the first deportations would ultimately succumb; they were murdered either in Chelmno or in Auschwitz.

Conclusion

The Legend of the Lodz Ghetto Children is really a masterpiece of ghetto reality. The paintings lend themselves to many interpretations, and the Legend and the paintings together give a wealth of material to teachers. The Legend can be used to teach a number of subjects including the terrible days of the Lodz ghetto and the uniqueness of this ghetto with its workshops and vocational schools, the general subject of the predicament of children in the ghetto, and more specifically, children in the Lodz ghetto, and art and literature during the Holocaust.

The artists who were involved in the Legend project must have been profoundly aware that they were living in an unprecedented period that had to be documented as a testimony for the future. Above and beyond their need to create a record was their need to create. The act of creating gave meaning to their lives; it gave them food for their spirits if not for their corporeal bodies.

"Creative endeavor may not satisfy the stomach but it quenches the spirit, and that has an effect on the entire body… Art and poetry have a magic force that quenches you in the midst of the greatest afflictions… I never felt as hungry for bread as I felt hungry to create more and more."8

- 8. 8