In most of the history written on the Second World War, North Africa assumes secondary importance as compared with the main arenas of Europe and the Pacific War. In general, British interests in maintaining free access to the Suez Canal in Egypt and French or Italian colonial interests across the top of Africa fade in importance against the massive confrontation ignited by conflicting German–Soviet aspirations in Europe.

However, the theater of North Africa was intensely felt by the armies that fought there, the populations that lived there and the Jewish communities that suffered there during the war. Morocco and Algeria suffered under the pro-Nazi Vichy regime and Tunisia and Libya suffered German and Italian occupation.

This article presents some of the problems attendant to the study of North African Jewry during the Second World War. The crux of the discussion issues from real differences in the fates of European and North African Jewry, an unhealthy tendency to compare and quantify suffering, the concrete problem of German restitution to North African Jews after the war and varying readings of German intentions for North African Jewry.

- For the purposes of this article the wider, universal application of the term which would include millions of non-Jewish victims is irrelevant.

- Hanna Yablonka, Off the Beaten Track – the Mizrahim and the Shoah (Israel: Yedioth Aharonoth Books and Chemed Books, 2008), p. 253-254.

One of the central quandaries is the correct terminology to be employed when discussing the fate of North African Jewry. Does one talk about the Holocaust in North Africa or alternatively, discuss the effect of the war on North African Jewry during the period of the Holocaust?

The answer is clearly dependent on what is meant by the term “Holocaust”.1 Seventy years after the war, many people use the term to denote the mass murder of six million Jews at the hands of the Germans during the Second World War. North African Jewry was not annihilated. The question of German intentions vis-a- vis the Jewish communities will be dealt with below, but during the years of Vichy oppression in Morocco and Algeria and the occupations of Tunisia and Libya, less than a thousand Jews died in camps in North Africa, and of these, a small number in camps in Europe after being transported. By definition then, if Holocaust means mass murder, then a “Holocaust” did not occur in North Africa. The history of the Jews in this period should correctly be discussed under the threat of a looming Holocaust which did not materialize. However, if what we mean by the Holocaust also includes the series of stages that (in Europe) preceded actual mass murder – e.g., concentrating the Jews in specific areas, stripping the Jews of their professions, despoiling the Jews of their property and material wealth, and depriving the Jews of their liberty by sending them to labor and other camps, then …. we are face to face with the “looming” Holocaust in its preliminary stages with all the considerable suffering involved.

What actually happened in North Africa during the war years?

As stated above, Morocco and Algeria were controlled by the pro-Nazi forces of unoccupied Vichy France and the Jewish population in both countries suffered under harsh anti-Jewish legislation from the last months of 1940. These two countries held about 320,000 of the approximately 450,000 Jews living in the four North African countries. Many of the Nuremburg Laws enacted against the Jews of Germany in the mid-thirties were copied in Morocco and Algeria and the Jews found themselves in desperate straits with Aryanization of Jewish property, numerus clausus or limited quotas of Jews in schools, universities and places of work and other hardships. In Algeria, the psychological shock of having their long-standing French citizenship revoked by the Vichy government was an additional cause of insult at the level of undermining identity.

Many of the men were incarcerated in camps run by Vichy personnel and this difficult period in the lives of the two communities would only be terminated in November 1942. The French citizenship of Algeria’s Jews, revoked by Vichy, would only be reinstated by General de Gaulle in mid-1943.

Tunisia was the only country to be actually occupied by the German army for six months from November 1942 until May 1943. Similar anti-Jewish legislation to the laws in Morocco and Algeria was enacted in Tunisia and many young men were subjected to harsh conditions in forced labor camps. Albert Memmi, a young Jew growing up in Tunis, recorded his personal account of his experiences in a labor camp and how they escaped back to Tunis in his book The Pillar of Salt, which is reviewed in this E-Newsletter.

The story of Libyan Jewry is somewhat different from the three countries dealt with above in that Libya fell into the Italian sphere of interest. The Italian context at first sight is an apparent contradiction. The fascist regime of Mussolini in Italy, aligned as it was to Nazi Germany, would appear to be fertile hunting grounds for Jews in the framework of the Final Solution, and yet the percentage of Jews transported to Poland to be killed was proportionately very low to the rest of Europe. This positive image is reflected to a degree in the Italian administration of Libya where the Jews by and large enjoyed reasonable attitudes. The situation began to change with the vagaries of the battle currents in the region. A yo-yo effect of repeated British military victories and subsequent occupations replaced by German and Italian occupations all in the years 1941and 1942 had difficult consequences for the Jewish population in Libya who suffered markedly from Italian retaliation for Jewish support and preference for the British. Benjamin Doron is a survivor from Libya and was interviewed by Yad Vashem several years ago. Extracts of this interview appear in this e-newsletter and they present a very personal and riveting account of what is presented here in the historical context. To relate just one episode from his personal account, his father, who had helped the British during their first occupation, was sentenced by the ensuing Italian occupation for collaboration with the enemy and disappeared out of young Benjamin’s life until he met him years later, after the war, in Israel, without Benjamin being able even to identify who his father was!.

Compensation

In a strange fashion, the issue of North African Jewry and the Holocaust received a new focus in the mid-sixties when the question of German reparations arose. The Adenauer period after the war set in motion the possibility of German reparations to Jewish victims, and the World Zionist Organization under the presidency of Dr. Nachum Goldman was a central factor in the negotiations. This is correct as regards the treatment of European Jews. When it came to the question of reparations for Libyan Jews who had been held in the forced labor camp of Giado (Jado), according to Professor HannaYablonka, Goldman and his office staff were of no help whatsoever2. In fact, the reparations that Libyan victims did receive in the sixties were due to their own initiative and direct contact with the German authorities who recognized their claims.

The situation described in the few lines above belies a more complex relationship between the European and North African survivors of the war years and the Holocaust, especially in the Israeli context.

For readers of this e-newsletter less familiar with the sociology of Israel, the Jewish population in the Land of Israel pre-1948 and in the State of Israel post-1948 has been marked by contrasting waves of immigration with very specific and different cultural legacies and styles coming from Europe, Africa and the East. This fact reverberates within Israeli society to this day, adding both color and complexity to many aspects of life in the country. However, at the intersection of the Holocaust and the differing survivor narratives, the “unhealthy” tendency to compare trials and tribulations has sometimes come to the fore. Dr. Goldman’s attitude reflects an earlier tendency in Israeli society to see the Holocaust as a European Jewish tragedy and these early attempts of Jews from North Africa to redress the wrong and receive recognition as survivors and compensation for material losses were unfortunately rebuffed by the European dominance in those years. Thus, the German recognition of North African suffering is an incontrovertible statement about that suffering. The unfortunate human tendency to compare pain should not blur the historical lines of what happened in North Africa under German and Vichy oppression.

New evidence, research and interpretations concerning the Holocaust are unfolding constantly. Thus, we read that newly-placed claims for reparations from Algerian, Tunisian, Moroccan and Libyan Jews are now being recognized.

It should be added that communities of North African Jews are to be found in countries outside of Israel like France and Italy and further afield so that the above discussion definitely has a wider geographical application and relevance than the Israeli context alone.

Nazi Application of The Final Solution in North Africa

As indicated above, the North African Jewish population of nearly 450,000 was spared the fate of the Jews of Europe. So we are looking at the reasons why close to half a million Jews in North Africa who were metaphorically a stone’s throw from the grasp of German forces were not murdered.

The historical fact of the German defeat at El-Alamein in November 1942 by the British and their subsequent ejection from the North African arena a few months later with American support in Operation Torch left a battered and bruised community of Jews in the regions under discussion. But they were alive. So the flow and ebb of armies across the top of the continent and Montgomery’s defeat of Rommel provide us with a human landscape of suffering with a minimum of death.

The question of German intentions remains to be dealt with. Was the fate of Jews in this region intended to be as it was in Europe?

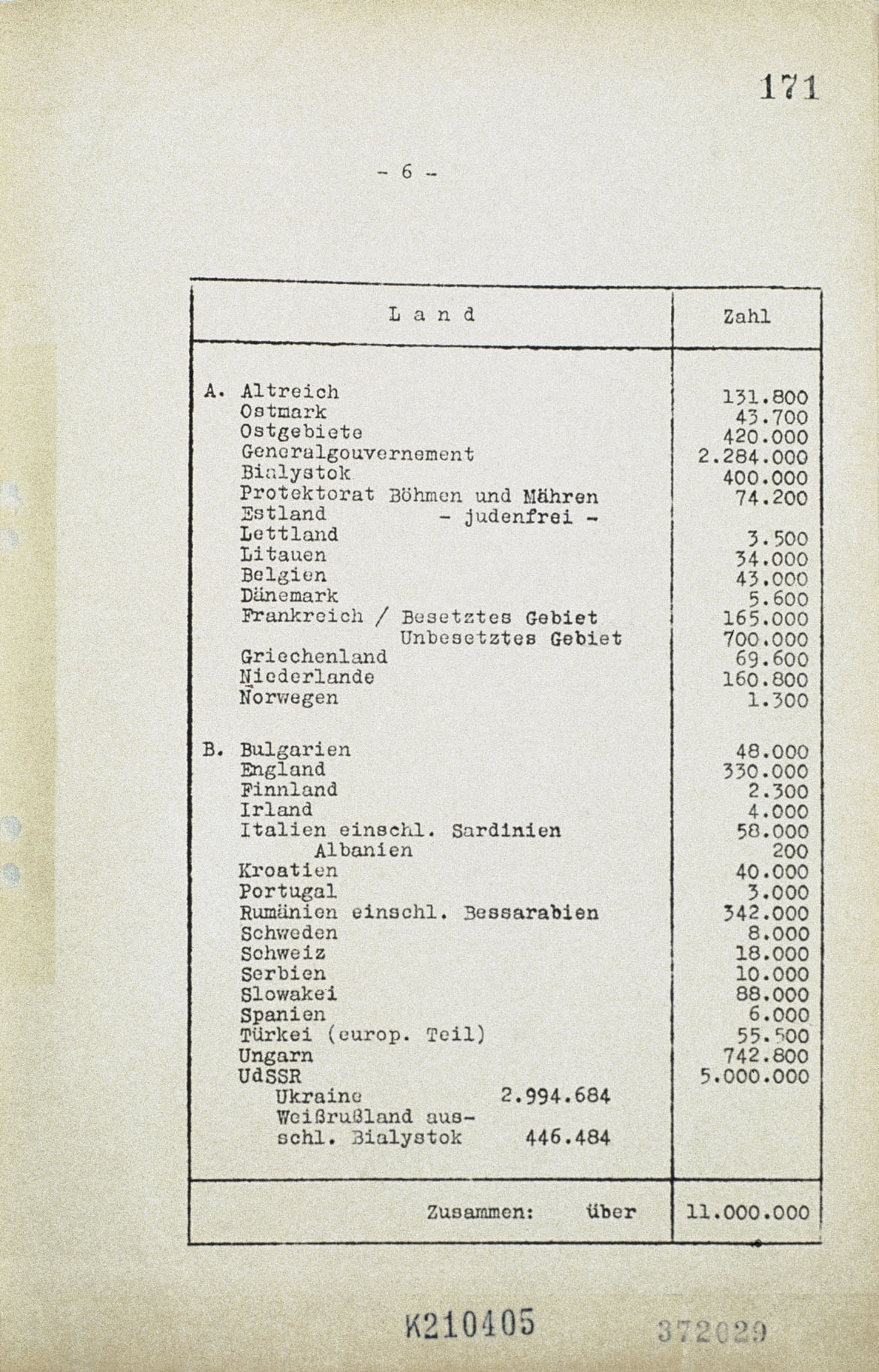

At the centre of this question, the reader of history faces a German war document called the Wannsee Conference Protocols, dated 20 January, 1942. The document is more than ten pages in length but the heart of it is a table with the Jewish population of European countries, occupied and unoccupied, specified for the purpose of being transported to their fate in the gas chambers built in Poland. North Africa comes into contention with the number of 700,000 under unoccupied France. There were below 350,000 Jews in both the occupied northern part and the unoccupied southern part. Thus the Wannsee number of 700,000 requires explication.

Some historians believe that the inflated number includes the Jewish population of the French colonies in North Africa under Vichy rule: Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria. Other historians deny this and give alternative theories. Within the framework of this e-news letter the minutiae of the disagreement will be left aside to make the following point, which we see as overriding: whether North African Jewry was or was not included in the figures of Wannsee, proof of German murderous intentions is to be found in a number of indicators:

- the “Einzatzkommando Ägypten” under Walter Rauff’s command waiting in the Greek wings to move south and begin “work” on the Jewish question in both Palestine and North Africa. Einzatzgruppen units were the death squads;

- the damning report penned by Dr. Gebhard Walter from the German Consulate in Libya on May 12, 1942, stating that the Jewish problem would, without doubt, be dealt with in good time in Libya;

- Hitler’s meeting with Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem in Berlin in November, 1941. This is a third example of evidence that points to a wider application of the Final Solution beyond the borders of Europe. His comments to Husseini indicated that Arab forces would be a welcome addition in the future to the “war” to be waged against the Jews in the area under discussion (including of course, Palestine). The existence of Nazi propaganda printed in Arabic-language leaflets which was being distributed in North Africa is part of the preparation for future cooperation in the extended war against the Jews.

So it appears that there are grounds for understanding, with or without Wannsee, that the Nazi ideology of racial “treatment” was to receive practical application at some point in the future with ensuing military victories. The German defeat at El-Alamein thus appears as a juncture at which a million lives of Jews were saved.

Concluding Thoughts

The Second World War unleashed waves of suffering on vast populations across continents and oceans for six long years. The theatre of war addressed in this article was undoubtedly secondary to the centrality of the clash in Europe and the Pacific Basin. However, what has been described above in North Africa is the effect of war decades into the aftermath of that war: survivors and their need for recognition, ongoing research and varying interpretations, the role of Germany then and today in the lives of people living on another continent and the crucial question of Nazi intentions on that continent.