- Judith Levin and Daniel Uziel, “Ordinary Men, Extraordinary Photos”, Yad Vashem Studies XXVI (1998), p. 272.

- Ernst Hiemer, Der Giftpilz, Nuremberg, Stürmerverlag, 1938.

- Uziel and Levin, “Ordinary Men, Extraordinary Photos”, Yad Vashem Studies XXVI (1998): p. 280.

The photographs taken by German soldiers and police officers of the abuse, deportation and murder of the Jews they encountered in the occupied Eastern territories starting in 1939 still hold the power to shock and horrify us more than seventy years later. These photographs are the result of the camera being used as a weapon to commemorate acts of violence, brutality and cruelty committed against helpless victims.

But what is the impetus behind taking such pictures – why were they taken? And if we then understand that these photographs were not only taken, but were distributed and placed into carefully organized albums, how will that affect our analysis of the photos?

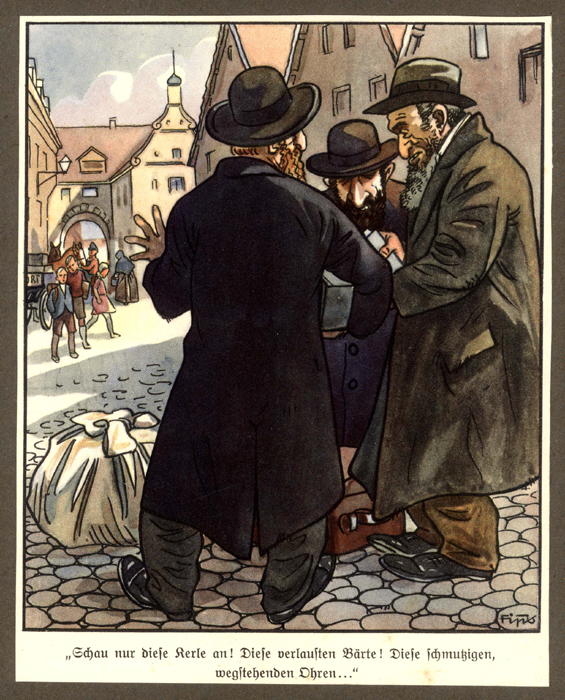

The all-pervasive, insidious antisemitism with which these photographers were inundated beginning in 1933, when the Nazis came to power, was the lens through which they photographed their Jewish victims. The most visible target of those years of indoctrination were the Ostjuden - the Jews from the East. The Ostjuden were unlike their counterparts in Germany and Western Europe who had assimilated into the local culture. The greater majority of these German and Western European Jews were indistinguishable in dress, language, and demeanor from their neighbors. In contrast, the eastern Jews – those from Poland and the Soviet Union – seemed to confirm the antisemitic stereotypes the Nazis used in their propaganda. Many of the Jews in the territory of the Soviet Union and Poland were religious Jews, and wore traditionalclothing – including long, black gabardines and ritual garments like prayer shawls (tallitot) – along with full beards and side locks (paot). They looked "different." Many lived in impoverished conditions imposed upon them throughout the centuries by unsympathetic rulers and antisemitic governments. These Ostjuden spoke a strange and guttural language called Yiddish. They truly were the “other.”

Starting in 1939 with the invasion of Poland, and in 1941 with the invasion of the Soviet Union, German citizens who had been exposed for years to persistent Nazi antisemitism now became soldiers and policemen in the very territory these Ostjuden – the objects of their hatred and fear – inhabited. To these soldiers, this eastern territory was outside of the borders of western civilization, a dangerous place, devoid of culture and the rules governing the civilized west. If the Slavic people in the east were to be dealt with in a pitiless way befitting the barbarians and subhumans the Nazis perceived them to be, the Jews of the East were to be eliminated in their entirety, murdered in unprecedented numbers. As this final solution to the Jewish question – mass murder – began in the summer and fall of 1941, German photographers were on hand to capture the scenes for posterity. Their photographs capture and confirm the negative stereotypes of the Jews that they had been spoonfed for many years previous. Many of their photographs are so extraordinary in the violence they depict that they go beyond the boundaries of decency and normalcy to another place altogether.

As discussed by Daniel Uziel and Judith Levin:

Photographs generally reflect norms and values of the photographer’ society and express moral correctness or incorrectness in this society or a certain segment thereof. If the photograph meets this definition, it is not extraordinary, in Nazi society; it was conventional to regard Jews as pathogens that should be expunged in one way or another. Removal of the Jews is even perceived as an existential necessity: in this case, it corresponded with the norms of this society.1

The picture below was taken in 1939 in Poland and is one of hundreds of photographs in the Yad Vashem archives documenting cases of abuse of Jews at the hands of the Wehrmacht and not the more fanatically antisemitic SS. Understanding that an army soldier took this picture, and not the SS, who were traditionally much more antisemitic, we can understand that the pervasive propaganda generated by the Nazis took its toll among “ordinary men” as well.

- 1. 1

In the photo, a large group of jovial young soldiers towers above a traditionally dressed Jewish man, almost completely surrounding him. In the left foreground, one young man, hands on his hips, turns his head to regard the photographer with a smirk, inviting him to witness the fun. The grinning faces of the soldiers belie the obvious enjoyment they are taking from inflicting such humiliation on the Jewish man trapped in the center. His stoical facial expression is harder to decipher, but his body language is not – his left hand is clenched into a tight fist, his body is stiff, his shoulders are hunched. His tormenters are clearly posing for the photographer, laughing, as – scissors in hand – they cut off his beard, and dangle his shorn hair from their fingers. The photo depicts a quintessential act of bullying, the mob mentality, and the power of many against one. The Jewish victim is rendered voiceless, powerless, a mere object of amusement. The photographer is clearly one of the crowd as his comrades pose and smile for his lens.

What is the purpose of this photo? Why was it taken? Many of these young men would probably have read Der Giftpilz2 ("The Poisonous Mushroom"); a childrens’ book, which presented illustrated warnings of the evils of the Jews. One excerpt deals specifically with the “Eastern Jews“.

The scene of the next story is a small German town. School-children stop in the street to observe and comment on three “Eastern Jews.”

“Look at those creatures!” cries Fritz.

“Those sinister Jewish noses! Those lousy beards! Those dirty, standing-out ears! Those bent legs! Those flat feet! Those stained, fatty clothes! Look how they move their hands about! How they haggle! And those are supposed to be men!”

“And what sort of men?” replies Karl. “They are criminals of the worst sort.”

- 2. 2

To these soldiers, their hapless victim is the embodiment of these “criminals”. The German people were taught not only to hate the Jews, they were taught to fear them as well. The Jews were evil. They were threatening. They were part of a conspiracy to take over the world. As such, when these soldiers met the Ostjuden and were able to first humiliate them and then photograph them, the photograph became a trophy, proof that they, members of the superior Aryan race, had encountered the enemy, subdued and humiliated him, and rendered him powerless. The pictures were taken for an audience which, having an antisemitic background similar to the photographers, would have appreciated, enjoyed and probably admired the efforts of their comrades in subjugating their Jewish victim and all that he stood for.

Many of these trophy pictures were found by censors among items being sent back by soldiers to their homes in Germany; many were posted or hung up at army bases so that anyone who wanted a copy – a trophy of his own – could order a print. This is almost as shocking as the pictures themselves – the fact that the Germans were so proud of their exploits that they treated these pictures as souvenirs. The wide distribution of these pictures among the German soldiers at the front tells us that we must see these pictures with a discerning eye: the camera really was wielded like a weapon to kill the Jews. The dehumanization suffered by the Jews merely by being humiliated for the photographer’s sake was the first step on the ultimate road towards their murder. What is being commemorated here are acts of violence, brutality and cruelty committed against helpless victims – the Germans had conquered their fears concerning the Jews, and had confirmed the demeaned status of the Jews as untermenschen – subhumans – by photographing them this way.

It is interesting to note that these soldiers were not under any official orders to abuse and humiliate the Jewish civilians they encountered in such a way. This knowledge renders this genre of picture “extraordinary”, in that they are a “depiction of religious or racial abuse beyond the perpetrator’s call of duty.”3

- 3. 3