Introduction

The Third Reich entered the annals of history as the most extreme aberration of civilized society. Its benchmark was the murder of millions of people in the name of an elaborate ideology that planned to divide the world into superior and inferior race groupings. From 1933 until 1945, the Nazi leadership planned, organized, and executed their ideas, inflicting relentless misery in the European arena. Nearly seventy years after the war, the singularity of the period still generates more attention than most other episodes in history.

This essay, as part of that phenomenon, is the second of two to appear in Yad Vashem’s e-newsletter on the aspects of a cultured country whose cultural legacy is subverted by the new regime to serve its ideological aims. (The first article is online and titled, "The Third Reich and the Theft of a Musical Legacy"). Ghettos, camps, marking, maiming, and murder are not the object of study here. However, to attain levels of persecution involving all the above and to the extent the Nazis succeeded, presupposes a level of control of every aspect of life in a country, including the cultural realm.

The focus of the essay is the sphere of classical music in Germany after 1933 and the largely successful attempts of the new regime to control the repertoire and everything connected with music for all the music-loving Germans in Germany and, from the outbreak of war, in the conquered territories as well. The article will cover aspects of the intricate relationship that developed between the regime and two of the most conspicuous conductors in Germany during the Reich, Wilhelm Furtwangler and Herbert von Karajan. They were to a large extent the public face of German culture that the world saw. Just as the international value of the Berlin Olympics in 1936 was of major importance to the rulers of the Third Reich, so was the continued prominence of German music and culture on the world stage high on the "political" agenda of the Reich leaders. In fact, according to Eric Levi in his book, Music in the Third Reich, five prominent Nazis were in the forefront of this internal Nazi battlefront, for such it was. None other than Goering, Goebbels, and Alfred Rosenberg, three of the five, were in virtual competition with each other in their efforts to garner additional spheres of influence. In this struggle, the visible faces of the conductors became the pawns of these powerful men. How each reacted to the inevitable pressures will be examined below.

Von Karajan

When Hitler came to power in 1933, von Karajan, as a rising musical meteor in Germany, was all of 24 years old. Fifteen years later at the end of the Nazi era, after investigations by Allied authorities, he became the German musician with the longest "sentence" of enforced unemployment which lasted for two-and-a-half years. He, who would become the dominant figure in German music after the war, constantly faced demonstrations and accusations based on his "war behavior" whenever he conducted in the United States. No persons ever presented pointed evidence against him and the atmosphere of guilt surrounding him appears to have been circumstantial.

However, von Karajan became one of the few senior musicians in Germany to join the Nazi Party. Many emigrated and most of the others remaining in Germany kept their distance from the Nazi party. The date of Karajan’s enrollment in the party is in doubt. The fact of his enrollment is not. Copies of his party card and their registration numbers show that he applied twice, once in Austria and the second time in Ulm, Germany; both applications were as early as April and May, 1933. He claimed a later date of 1935 and connected his enrollment with the formality of becoming the music director of Aachen.

What he did as a Nazi member or sympathizer in these two years will probably remain an open question unless more documentation is unveiled. He had connections with other Nazis and SS members in this period and at the young age of twenty-eight he landed the plum position of opera conductor of the Berlin State Opera.

Beyond voluntarily becoming a member of the Nazi party, his activities on behalf of the Nazi regime were various and visible:

- He conducted tributes on the occasion of Hitler’s birthdays during the coming years.

- He conducted at the official celebration of the Reich after the annexation of Austria.

- He dutifully presented programs of inferior musical propaganda material, and after the war broke out, his clean-cut chiseled face was an integral part of the picture-perfect cultural representative of the Third Reich on the podiums of captured European capitals.

There is no doubt that the individual musicians enjoyed a surge in their financial situation as a result of Karajan’s unparalleled success in the emerging recording markets but this came together with the price tag of enduring an autocratic mien that became the core of Karajan’s projected image. He created an aura around him that has been likened to Hitler’s Fuehrer image and although this kind of "talk" smacks of the sensational, Karajan grew up in the Nazi era, became a member of the party and never once disavowed his Nazi connections after the war. He has been accused of using antisemitic slurs about various Jews in his music circles despite their presence in his entourage.

It has been said of the famous German philosopher, Martin Heiddegger, that his war-time Nazi affiliation and sympathies are dwarfed in their importance by his refusal to recant in the face of various approaches made to him after the war. The same atmosphere surrounds the silence of Karajan after the war. For many people, the undeniably beautiful recordings that he made after the war are besmirched by his silence. Karajan can be seen as an example of the relative failure of denazification in Germany after the war, bearing in mind that with everything described above, he achieved well-nigh total hegemony in the postwar world of classical music.

Furtwangler

At forty-seven, Wilhelm Furtwangler was double the age of Karajan when the Nazis rose to power in 1933. Not a rising meteor but the shining northern star in the German music firmament, Furtwangler, the foremost representative of the German music legacy in Germany and around the world, was suddenly thrust into the maelstrom of Nazi totalitarian politics, and without prior experience in the razor-edged world of political manouevering, had to secure his position in a very insecure arena.

His situation was more precarious than Karajan’s if only for the simple reason that he never joined the Nazi party and for the most, fought for the right to retain his artistic independence. Other internationally recognized "faces" of German music had been world-renowned names like Bruno Walter and Otto Klemperer, who as Jews were forced to leave Germany after 1933. Furtwangler remained the preeminent conductor in Germany after 1933 and his unenviable choices with the ensuing paths that he trod have brought both opprobrium and high regard for the stances that he adopted.

The complexity of his situation stems from his initial decision to remain in Germany after 1933 in order to fight for musical autonomy from within the new reality of a totalitarian politics.

After the war, The Berlin Philharmonic never again enjoyed the same surge that came from a feeling of togetherness and community, as they had under Furtwanger.

The authority struggle that developed between Furtwangler and Goebbels is fascinating because both men needed each other to achieve their own aims. At the simplest level, Furtwangler needed the continued financial backing of Goebbels to keep the Berlin Philharmonic solvent and Goebbels needed Furtwangler’s international standing to further the façade of German culture. There was a constant "give and take" in their relationship that mirrored the tension between the domain of art and music and the world of power politics. No totalitarian regime can afford a demonstrative creativity and independence from any agency under its aegis that admits values other than its own. An autonomous world of music would permit deviations according to guidelines external to the regime’s dictates. Goebbels had the power to crush any unorthodoxy if he so wished and yet a subtle relationship of toleration within limits existed between the two. Furtwangler collaborated and Goebbels displayed flexibility.

Any judgment of the famous conductor would have to take the following points into consideration:

- His decision to remain in Germany when voluntary exile was a definite option for him was taken with a view to maintaining artistic integrity and minimizing the invasive inroads of the political superstructure.

- As mentioned above, Furtwangler, the very visible figurehead of German music, refused to join the Nazi party. As an outsider, he remained suspect and susceptible.

- He refused to conduct musical scores created for Nazi leaders.

- By and large, he avoided conducting at Nazi functions in an attempt to minimize the visible aspect of his collaboration with them.

- As far as possible he avoided conducting in countries occupied by the Wehrmacht.

- He refused the showering of gifts, like a house from Hitler himself and several cars from Goering.

- Furtwangler intervened on behalf of Jews and other victims of the Reich’s racist policies and brazenly offended Nazi principles by continued association with them. He was unable to save his loyal Jewish personal secretary, Dr. Berta Geissmar, who was forced to leave Germany and settled in England. She had been his organizational lifeline and the concentrated effort of the regime to expel her indicates the extreme reaction of the Reich leaders vis-à-vis Furtwangler’s Jewish associations.

Berlin, Germany, Hitler, Hess, Himler, Goebbles and other senior officials at an SS concert, profits of the concert were dedicated to the winter charity project, 07/12/1933

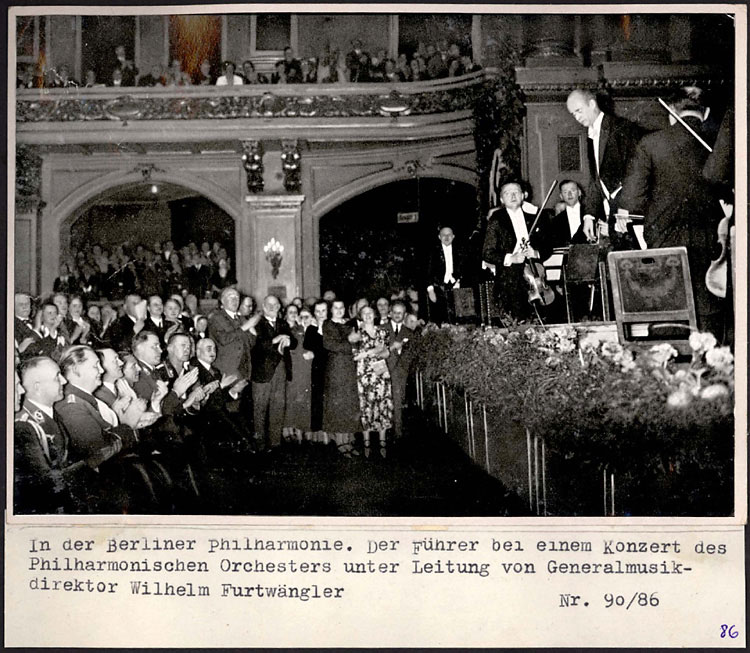

Despite the points listed above, Furtwangler’s record before and during the war was sullied by the very fact that he had collaborated with the regime. Émigré musicians especially were incensed that he had lent his honorable presence to Nazi legitimization in the eyes of the world. Berta Geissmar insisted that contact with Nazi officialdom was necessary if any attempt was to be made from within in the struggle of art against politics. Whatever his actions, one photograph of his bowing after a concert of the Berlin Philharmonic with Hitler, Goebbels, and Goering sitting in the front row looks very much like unbridled collaboration. But the critics weren’t in the hall to hear the applause of adulation from the audience for the beloved national figure of Furtwangler. The regime’s leaders were, and even to them it was clear that a nuanced approach with this national treasure was advisable. Of all the prominent names in German music, Furtwangler alone remained to struggle for German artistic autonomy.

Conclusion

The two cases of Furtwangler and Karajan portrayed here indicate the importance of the world of culture and art to the Nazi regime. All the evidence shows that before the top echelon leaders would apply themselves to murderous racist policies, they were intimately involved in efforts to control art in the Reich on all fronts. “Decadent Art” was curtailed as antithetical to new artistic conventions of the Reich and the world of jazz was also targeted.

Clearly, the magnificent achievements of German classical music could be retained as a beacon of light for the new Germany but naturally within the limits of new parameters. The narratives of Furtwangler and Karajan help to illustrate the tensions that began in 1933, and the different paths that two prominent musicians chose in confronting the Third Reich.