- Rachel Bernheim-Friedman, Earrings in the Cellar (Hebrew), Moreshet, 1999, pp. 11-12.

- Peretz Litmann, The Boy From Munkacs: The Story Of A Survivor (Hebrew), Haifa, 1996, pp. 16-17.

- Peretz Litmann, Ibid., pp. 22-23.

This article presents a short summary of the history of the Jews of Munkács. It is presented here for the sake of comparison with the history of the Jews of Budapest, the largest of the Jewish communities in prewar Hungary, profiled in a separate article in this newsletter. Whereas Budapest's Jews were, for the most part, assimilated Jews, Munkács was a major center of Hasidic life and learning. While Budapest remained relatively safe until October, 1944, the Jews of Munkács were among the first of the Hungarian Jews to be deported to Auschwitz, in May, 1944. Many additional comparisons can be made between these two communities.

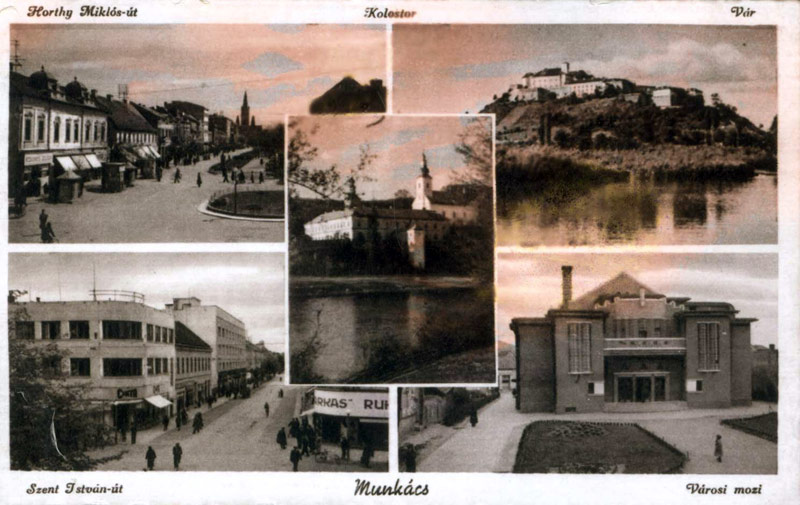

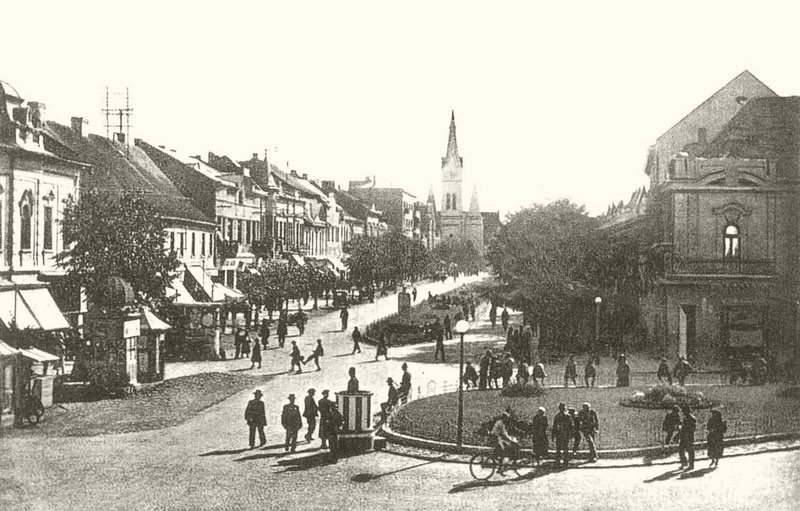

Today, Munkács, or Mukachevo in Ukrainian, is a city in the Transcarpathian region of the Ukraine. Until 1919, it belonged to Hungary. It then became part of Czechoslovakia until 1938, and from 1938 to 1945 it was again part of Hungary. From the end of World War II it was part of the Soviet Union, and after 1991 it became part of the Ukraine. These changes are reflected in the history of the Jewish community of Munkács as well.

The early days of the Jewish community in Munkács are reflected in documents that date back to the early 18th century. According to the documents, Jews settled there in the second half of the 17th century; there is some evidence that a few isolated Jews lived in the surrounding area prior to this period. In 1711 the town became the property of a noble family that was favorable to the Jewish population of the area and allowed Jews to settle there as long as they paid special taxes. Munkács Jews were engaged in trade, mostly between Galicia and Hungary, worked as craftsmen and some were even farmers in the surrounding areas.

The Jewish community in Munkács grew when Jews arrived from neighboring Galicia, which was also part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. From 80 families in 1741, the Jewish community numbered 5,049 (47.9% of the total population) by 1891, and this percentage stayed more or less constant through 1930. Munkács became an important Jewish community in Hungary within a relatively short period. In 1930, 88% of the Jewish community registered their nationality as “Jewish.”

The Jewish community of Munkács was known for its conservatism and inclination towards Hasidism, on the one hand, and for its many enterprises in modern contexts, such as Hebrew education and Zionist activities, on the other. Historians attribute devotion to Hasidism by many Jews in Munkács to the location of the town, far from the urban centers such as Vienna, Budapest and Prague. The devout Hasidism of Munkács is also explained by the scenery of the Carpathian Mountains, which evoked a mystic experience.

“The city where I was born was called Mukacevo by the Czechs, or Munkacs, as it was known in Hungarian […] From an economic, municipal and cultural point of view, Munkacs was considered an important city. In our area, diversity was outstanding in every way possible. First of all, the scenery […] covered with green trees all year long. Forests, wide expanses of green fields, and many streams of water, such as the Latorica River cut through our city, their waters flowing, along with all the waters from the streams, southward to the Blue Danube. And similarly, the population was diverse. There were German and Hungarian speakers among the elderly population, who had lived there from the period when the area was under the Austro-Hungarian Empire. And there were many minority groups that originated from adjacent countries, such as Poland in the north, the Ukraine and Russia in the east, Romania and Hungary in the south, and of course, our people, the Jews.”1

- 1. 1

As modernization and enlightenment made their way into the community, the struggle between those who advocated changes and adaptation to the new world and those who adhered to the traditional way of life was particularly intense in Munkács and its surroundings. Following the split between Orthodox and Neologs only a few joined the Neolog movement and a small community was established in Munkács.

During the interwar period Jews participated actively in the administration and the political life of Munkács. The Zionist party of Czechoslovakia, the country to which Munkács belonged in that period, had many supporters. The Orthodox non-Hasidic community in Munkács belonged to the circles of the Chatam Sofer from Pressburg (Bratislava), at that time in Hungary (at present the capital of Slovakia). Judaism in Carpatho-Rus remained a bastion of Jewish conservatism, and even spearheaded anti-Zionist and anti-Modernist ways of thought among Jews of Eastern Europe.

Domestic Life, Culture, and Education in Munkács

The average Jewish family in the rural districts lived in houses built from locally available natural materials. The houses usually had one room, and maybe a kitchen. There were large windows, and because many of the houses lacked a chimney, they were usually full of smoke. The privies were located outside the houses, and there were no showers or running water. Water was drawn from wells in the courtyards or from springs and streams near the village. Jews tried to live near each other, and their houses were located in the middle of the town.

The patriarchal Jewish family preserved its structure even in times when modernism shifted this traditional familial structure. Life was difficult, and supporting a family was an enormous endeavor. In accordance with Jewish tradition, fathers saw themselves as responsible for the education of their children. Peretz Litmann, a native of Munkacs, remembers:

“When I was 3½, I started at the cheder [religious elementary school]; altogether we were four children. I remember that in honor of my arrival, Mother brought candies, and all the children threw them at me, a rare custom, because they did not spoil us with luxuries like that very often. The parents paid for the studies with the rabbi, of course, and one can assume that he was not very rich, since he lived very frugally, with extreme thrift. At first I learned the Hebrew alphabet, and at the age of 4, I could already read the prayers from the siddur [prayerbook], just like a big boy, without understanding the prayer. After that, I learned to write, and at the age of 6, I already knew chumash [the Five Books of Moses] with Rashi’s commentary. Every Thursday I recited verses from the Bible by heart, including the translation from Hebrew to Yiddish.”2

With the growth of the Jewish population Munkács became the educational and cultural center for the Jews in the region. Four Yiddish periodicals were published in Munkács. In 1871, a Hebrew press was founded and many Hebrew books were published in Munkács until 1944. In 1920, a Hebrew elementary school was established by the Organization of Hebrew Schools in Subcarpathian Ruthenia, and it became popular both in Munkács and the surrounding towns. A Hebrew secondary school was established in 1925. At the outbreak of World War II there were approximately 30 synagogues in Munkács, many of them Hasidic.

In the text below Peretz Litmann refers to the unique nature of his hometown, as expressed in the ability of Jewish residents to live together despite the differences that existed between their political, social, and religious views. He summarizes this topic from his personal experience:

“All the Zionist movements were active in the schools, and sometimes we had to participate in street fights with the yeshiva students. The children that belonged to the secular Zionist camp had to fight on two fronts: the ultra-Orthodox and the Gentiles. That is why we usually went around in groups, being afraid to move about alone, lest we run into a Jewish chasid or a Gentile bully. We learned not to give in to either of them, and if that was not enough, I, who came from a Polish background, was a minority within my own camp, and I had to be vigilant and be the best, something that in retrospect, shaped my personality.

Despite the arguments and the essential differences in the world view from a religious, nationalist, Zionist, and socialist point of view that espoused freedom and assimilation, Munkacs was considered a treasure in everyone’s heart.” 3

Munkács after the First World War

In 1921, some 10,000 Jews lived in Munkács – half the town's total population. The Jewish community of Munkács began to become exposed to the modern, diverse world outside, and there were two opposing camps: the Hasidim led by Rabbi Elazar Shapira and the Jews that had abandoned all their religious obligations. Nevertheless, all of Munkács's Jews were involved in the Jewish life of the town: right-wing Zionist groups, worker and socialist anti-Zionist organizations, communists and anti-Zionist religious groups.

When Munkács returned to Hungarian rule in 1938, the Jews of the town blessed their return, but their optimism was soon brought to an end. The Hungarian authorities persecuted the Jews from the beginning of their annexation of the town. Jews fell victim to physical violence, abuse and robbery. The authorities harassed Zionist groups, limited the Jews' economic activities, and recruited many men for forced labor in the Hungarian army.

On 19 March 1944, the German army invaded Hungary and four weeks later, the concentration of Jews began. Jews from Munkács were forced into two ghettos, and those from the surrounding areas were assembled at two brick factories on the outskirts of town. On 11 May 1944, the deportations to Auschwitz began, and on 23 May the last deportation train left Munkács.