- Translated from the historical introduction by L. Rotkirchen, in: M Zandberg, A Year Without End, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem 1966, p. VIII.

- Móricz Zsigmond 1935, Kinga Frojmovics, A zsidó Budapest, Komoróczy Geza (Ed.), MTA Judaisztikai Kutatócsoport, Vol. 1 (Hungarian), Budapest 1995, p.120.

Introduction

This article presents a short summary of the history of the Jews of Budapest, the largest of the Jewish communities in prewar Hungary and the Hungarian capital. For the sake of comparison, we have also included in this newsletter a profile of another town in Hungary, the provincial town of Munkács located in the Carpathian Mountains. Whereas Budapest's Jews were, for the most part, assimilated Jews, Munkács was a major center of Hasidic life and learning. While Budapest remained relatively safe until October, 1944, the Jews of Munkács were among the first of the Hungarian Jews to be deported to Auschwitz, in May, 1944. Many additional comparisons can be made between these two communities.

The Jews of Budapest: A Brief History

The first indication of a Jewish community in Hungary can be traced to the first Jews who reached the “water line” of the Danube River, where the ancient city of Buda was located, during the time of the Roman Empire. This small Jewish settlement continued to grow during the Middle Ages. In 1251, Bela IV, the King of Hungary, granted them the right to legal residence in the city, and religious autonomy.

Jews were engaged in commerce and in finance, and the royal court often turned to them for funds. Most of the subsequent kings of Hungary honored these rights, and ensured the conditions necessary for observing the Sabbath by closing off the Jewish section of the city for the duration of the Jewish day of rest. Despite this apparent tolerance and consideration for the Jewish minority, church officials forbade common residences for Jews and Christians.

In 1360, King Ludwig I expelled Jews from Budapest, but five years later they were invited to return and their rights were reaffirmed.

In 1474, at the initiative of King Matyas, an official representative body of the Jews of Hungary, Praefectus Judaeorum, was established, comprised entirely of Jews who lived in Budapest.

From the Ottoman to the Austrian Conquest

In 1526, the Ottomans conquered Budapest, and the lives of Jews in Budapest changed for the duration of the 150 years of Ottoman rule. The Ottoman Empire encouraged the settlement of Jews, and Jews engaged in commerce and finance in Budapest, often occupying official posts as inspectors and tax collectors.

In 1686, the Austrians conquered Hungary. This ended a period of heavy fighting between the Ottoman Empire and the Austrians, and also ended a period of prosperity for the Jews. The Jewish quarter was plundered and Torah scrolls were burned. However, over the next century, the empire strove to maintain a higher level of tolerance to prevent inner tension between different minorities in the empire.

The new Austrian regime imposed heavy fines on the Jews at the onset of its rule, but as soon as the resettlement of Budapest began, settlers from many parts of the Austrian Empire – Germans, Slovaks and others, including Jews, arrived in increasing numbers, first from Bohemia and Moravia and later, from Galicia, after this region was integrated into the Austrian monarchy. During the 17th century the Jewish population increased from 20,000 to around 80,000. The Toleration Decree issued by Emperor Joseph II in 1781 allowed Jewish settlement in the free royal towns, as well as the establishment of their own schools, and it also enabled Jews to engage in trade and commerce and to own property. Jewish life in Budapest developed rapidly, and flourished considerably during the 19th century.

During this period, the section of the city on the other side of the Danube, known as Pest, started to develop. In 1873, the two parts of the city were united, and became the capital of Hungary, known as Budapest.

The Dohány Street Synagogue in Budapest, Past View (Before it was Renovated)

The Impact of Modernization and the Enlightenment on the Jews of Budapest

In the middle of the 19th century, modernization and the spirit of the Enlightenment made their way into the Jewish community of Budapest. The new ideas of Jewish scholars such as Moses Mendelssohn of Berlin, who tried to modify traditional Judaism to suit the concepts of modernity, had an impact on many Jews, and those of Budapest were no exception. Aharon Chorin, one of the leading Jews in Hungary at that time, sought to make changes in traditional customs so Jews could better integrate into their surroundings. This endeavor created a new pattern in Hungarian Jewish life, known as the Neology Movement. This movement had characteristics similar to the Reform movement in Judaism. Reform tendencies had already appeared in the community organizations of Hungary from the beginning of the 19th century, and became officially organized in the 1860s.

The Budapest Jewish leadership decided that it was important to spread the standardized Hungarian language throughout the Jewish community. They established a Neolog synagogue similar to the Reform synagogue in Berlin, and also decided that the community leaders should be enlightened rabbis, capable of delivering their sermons in Hungarian, in order to educate the younger Jewish generation. They also advocated the integration and acculturation of Jews into Hungarian society.

This contradicted the traditional Orthodox Judaism of Hungarian Jewry, whose goal it was to preserve traditional Judaism. Thus, the Budapest community had two major differing viewpoints as of the 19th century.

Budapest Jews during the Revolt of 1848-1849

In 1848, a wave of revolutions swept through Europe, known as the Spring of Nations, or the Year of Revolution. Closely linked to other revolutions in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the revolution in Hungary in 1848 grew into a war of independence from Habsburg rule. In August 1849, the Hungarian revolution was suppressed. During the 1830s and 1840s, at times called the "Period of Reform" in Hungary, the “Jewish Question” was discussed in legislative institutions as well as in literature and in the press. The general tendency was in favor of granting civil rights to Jews, albeit with demands for religious and social reforms. The suppression of the revolution of 1848–49 affected the status of Jews, because many of them were active in the revolution. During the 1850s, judicial and economic restrictions regarding Jews were still valid. Most of these restrictions were abolished in 1859–60, and Jews were allowed to engage in all professions and to settle in all regions of the country. In 1867, a law granting equal rights to the Jews was enacted. Following this, there was a rapid growth of the Jewish population of Hungary, as result of internal growth as well as of immigration from neighboring regions, especially from Galicia.

Consequently, Jews of Budapest underwent an accelerated modernization process.

Budapest Jewry was known for its contribution to intellectual pursuits in Hungarian and Jewish literature, research, and journalism. The Association for Hungarian Jewish Literature was established in 1894 [I.M.I.T.]. During its existence, it published scholarly articles on topics of Jewish history and culture. The Jewish press, based in Budapest, influenced and shaped the worldview of Jews in Hungary. It reflected the diversity in Jewish identity, and included newspapers published by Neologs, Zionists, and by the Orthodox.

Jews of Budapest During the Interwar Period, 1918-1939

The Extent of Assimilation

During World War I Hungary, as part of the Habsburg Empire, was part of the Central Powers Alliance. By the end of the war its economy was on the brink of collapse. The defeat of the Central Powers brought an end to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and as a result, Hungary became independent. In 1919, the new Hungarian government presented a memorandum to the Versailles Peace Conference describing the status of its Jews:

"The majority of Hungarian Jews are totally assimilated among the Madiars… they gave the Hungarian nation writers, scientists and splendid artists. As a result of their assimilation into the Hungarian national spirit, it should be admitted that from a racial point of view they are no more Jews but Madiars."1

This document presents a harmonious situation between Jews and their neighbors, and emphasizes the complete integration of Jews into Hungarian society. In reality, however, the situation was more complicated.

The Rise of Antisemitism in Hungary

As mentioned above, the years following the Decree of Equal Rights for Jews were indeed years of growth and of integration. But in non-Jewish circles traditional avoidance of Jews turned into open hostility beginning in the 1870s. The Blood Libel of Tiszaeszlár in 1882-1883, which blamed the Jews of that village for the disappearance of a Hungarian girl and for her murder for ritual purposes, caused antisemitic riots in many places, including Budapest.

An antisemitic political party was established in the wake of the blood libel and its aftermath and in 1884 it had 17 delegates in the Hungarian parliament. Though a small party, it nevertheless succeeded at dragging out parliamentary debates on Jewish issues. In the mid-1890s, the People’s Party became the major advocate of anti-Jewish claims in Hungarian politics. It had a conservative-clerical platform and transformed the debate about Jews in Hungary from an economic and social basis to an ideological one. The Jews, they claimed, were rootless and lacking in any kind of affinity to Hungarian nationalism. Furthermore, they were spreading cosmopolitan secular ideas, opposing the true Hungarian spirit.

Historians conclude that during this period at the end of the 19th century the seeds of Hungarian antisemitism were planted, but that they were largely marginal in society. This changed after the Hungarian defeat in World War I. The Budapest Jews became the focus of hostility in the eyes of Hungarian nationalists who flourished in Hungary from 1918, and had to contend with a wave of antisemitism. The new ruler of Hungary, Miklós Horthy, even referred to Budapest as “the backsliding city” that strayed (as it were) from the true Hungarian spirit, and became a universal cosmopolitan center. Antisemites nicknamed the city “Judapest.” This antisemitic sentiment arose despite the fact that thousands of Jews had joined the Hungarian army during World War I, and hundreds had been killed in action for the “the beloved Hungarian motherland.”

- 1. 1

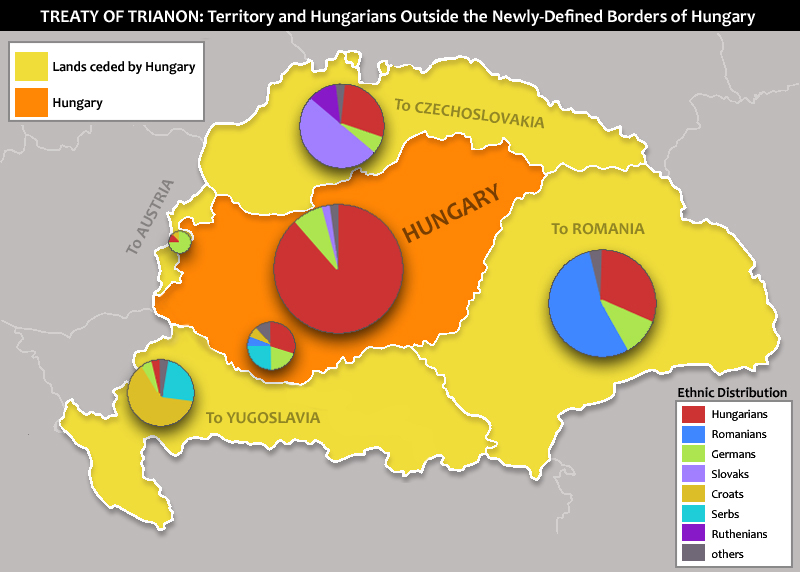

After the war, Hungary was politically unstable. Between 1918 and 1919, a civil democratic government was established, followed by a Communist revolution. All this turbulence had an impact on the lives of Jews. The liberal democratic government formed in 1918 was popular, but the victorious allies still considered Hungary an enemy, and demanded that it cede areas that the Hungarians considered integral to their country. These demands caused many Hungarians to turn eastward to the newly-established Soviet Union. The Hungarian Socialist and Communist parties formed an alliance, which was widely supported, and in March 1919, a Soviet Republic was declared in Budapest. Heading this Soviet republic was Bela Kun. Although he was born a Jew and never converted, Kun was completely alienated from Judaism. The Hungarian Soviet Republic lasted for less than a year, and with its demise Kun left Hungary for the Soviet Union and never returned. He was executed during the Stalinist purges of the 1930s.

The Jewish community at large was attacked and blamed for undermining the nationalist Hungarian foundation, and the view that "the Jewish revolution" was responsible for the national disaster was widespread during the inter-war period.

Jewish Cultural Life in Budapest During the Interwar Period

Jewish entrepreneurs organized and operated many of the cultural centers in Budapest, such as coffee houses and theaters. This phenomenon began with the Orczy-House, an attraction from the middle of the 19th century.

“It was a structure with low arches. With the passage of time, the tapestries lost their color, and the guests themselves aged. Who were the people that frequented the place? Furriers and textile merchants. You should know that millions changed hands here. Practically speaking, this is where the stock exchange was. That was the heyday of the café, when every day there were 50 carriages parked in the courtyard. That’s when the merchandise found its way here; this is where the city’s commercial arteries beat, among the three courtyards.”2

Many of the Hungarian movie actors of the 1920s and 1930s were Jews, such as Beregi Oszkár and Kabos Gyula. Some of them, such as László Korda, emigrated to the United States or to western Europe. Leslie Howard, whose Jewish name was Leo Stajner, studied at the Budapest Jewish school in 1904. He earned everlasting fame as Ashley Wilkes in the movie Gone With the Wind.

There is an assumption that the Neolog Jews, especially those in Budapest, termed “assimilationists,” did not have a strong Jewish identity, and were indifferent to everything associated with Judaism. However, most of them retained their Jewish identity, especially on a cultural-educational level. Converting to Christianity was somewhat common among Jews in Budapest between World War I and World War II, but it was not approved of by the Neolog community. On the contrary, most Jews saw conversion as a dishonorable and despised practice that should be opposed. They were not strictly observant people, but they operated a Jewish educational network in the city: a Jewish gymnasium was established in 1919 and Jewish intellectuals taught boys and girls at this school, offering general studies in Hungarian, as well as foreign language study as part of the curriculum. The school was equipped with a rich library and modern laboratories, and already in the 1920’s, it included movies as a means of instruction. Physical education classes produced several of the best Hungarian-Jewish athletes. The gymnasium students celebrated the national Hungarian holidays magnificently; they went to museums, and organized trips to Europe and to Eretz Yisrael until 1938.

This push to acquire a universal culture, together with developing a love for the Hungarian motherland, was combined with a broad Jewish education. The students studied Hebrew, translated sections from the Bible, studied Jewish history, and gathered together every Friday for shared Kabbalat Shabbat [welcoming the Sabbath] services, even if some of them had to travel by trolley to participate.

In 1938, there was a rise of economic and social distress among Jews in Budapest with the enacting of anti-Jewish laws by the Hungarian government. Like Jews of Germany, the Budapest community reacted to the new situation, and organized welfare institutions for the needy. An item in the annual report of the Jewish gymnasium stated that the school had collected winter equipment for needy students, and established advanced professional training courses so the students could support themselves within the limited conditions set by the anti-Jewish legislation.

In 1939 on the eve of World War II, there were about 200,000 Jews in Budapest.

- 2. 2