- Cohen, pp. 401-464.

- Cohen, pp. 437-474; Poznansky, pp. 493-503.

- Cohen, pp. 492-497.

- Union des Juifs pour la Résistance et l’Entraide – UJRE.

- Conseil Représentatif des Institutions Juives de France – CRIF.

- Poznansky, pp. 575-576. See also: Renée Poznansky, “The Zionist Youth Movements in France and Unity in the Jewish World 1940-1944” (translated to Hebrew by Ada Paldor), in: The Holocaust – History and Memory, Festschrift for Israel Gutman, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 2002, pp. 46-57 (Hebrew).

- CJDC, XXII-12; AN, AJ 38, 1097, in: Poznansky, p. 576.

The history of the Jews in France during the Holocaust and the Second World War constitutes a unique and complex chapter in the history of the Holocaust of European Jewry. Various factors combined to create a different reality than in the other countries under German occupation. These include the internal divisions in the Jewish community between veteran Jews and immigrants; the French Vichy regime and its collaboration with German interests relating to the persecution of the Jews; public opinion among the civilian population; and the underground and rescue actions by Jews and non-Jews. The following review will focus on these historical processes and events.

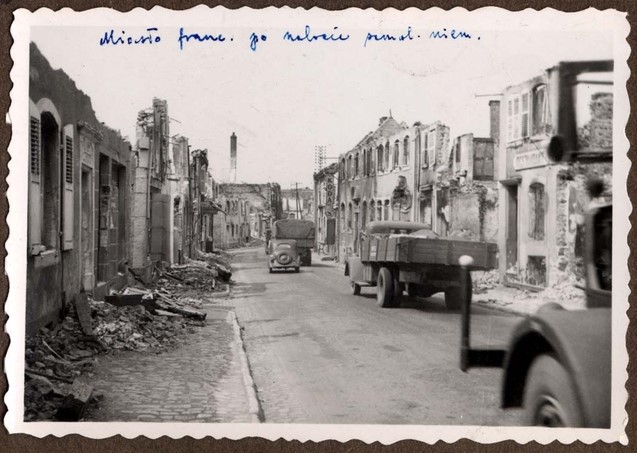

Following the First World War, France was regarded as the strongest power in Europe. However, despite its military achievements, it suffered from serious domestic problems, including a dwindling population, political instability, and the rise of extremist forces on both sides of the political map. Together with the growing military strength of Germany, these factors led toward the end of the 1930s to France’s ultimate surrender of the fortified Maginot Line and to the signing of a ceasefire agreement between Germany and France on June 22, 1940. About a month later, the members of the French parliament decided to abolish the republican regime in France and to grant full powers to Marshal Henri Pétain, who thus became “the head of the French state.” According to the ceasefire agreement, France was divided into five zones: a small area along the northeastern border was annexed to the Belgian military government; an area in the southeast was handed over to Italian rule; and Alsace-Lorraine was annexed to Germany. The two remaining zones, comprising the majority of the territory of France, were divided between France and Germany:

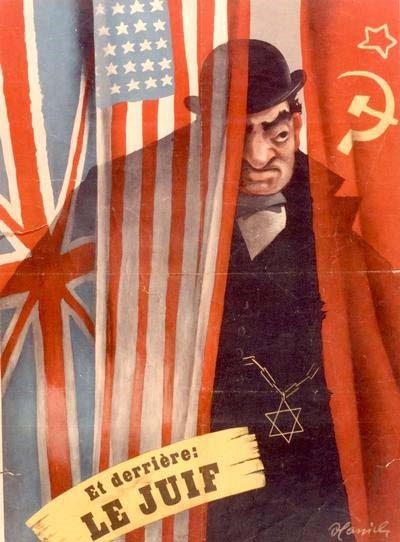

The Occupied Zone, under German rule, included the country’s West, North, and East, including Paris. The Free Zone, under the control of the new government led by Marshal Phillip Pétain and his deputy Pierre Lavale, covered the South of the coutnry, including the city of Vichy, where the government was based. At the time, Pétain was perceived not merely as a leader but as a redeeming messiah who would free France from its current condition and lead to national renewal. His policies were accepted by almost all sectors of French society, and he enjoyed firm support from political quarters adhering to contradicting ideologies. Bolstered by the nationalists’ demand “give France back to the French,” the Vichy regime presented its new principles – work, family, homeland – and began to limit the influence of foreigners and to curtail the rights of refugees and Jews. This approach fitted in well with the

broader agenda of French society, rife with anti-Semitism and xenophobia. In its first year, opposition to Pétain’s rule was confined to a very small group within French society.

At the time, the Jews of France were scattered in thousands of locales and rural areas. Approximately one-third of them held French citizenship – natives of the country who were also referred to as “Israélites.” The remainder were Jews who had emigrated to France from Eastern Europe around the end of the nineteenth century, or from Germany during the 1930s. They were regarded as “foreign Jews” or immigrants. After Hitler’s rise to power, thousands of Jewish refugees fled from the Reich to France, settling mainly in Paris, which accordingly was home to two-thirds of the country’s Jewish population when the Second World War broke out. In May 1940, the population of foreign Jews increased further after some 40,000 Jews fled from the Western European countries occupied by the Germans, such as Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. Accordingly, it is estimated that the number of Jews in France at the beginning of the occupation was around 350,000; over half of them were stateless. The veteran Jews regarded Pétain and his government as a legitimate and reliable authority that could help rehabilitate France following its defeat. By contrast, the foreign Jews refused to place trust in a government that was collaborating with the Nazi occupier. The division between Jews with French citizenship and foreigners was a stark one, evident to both the community and the regime. Indeed, the distinction would later become fateful, since Jews with French citizenship initially enjoyed protection, and the differences between the two groups widened considerably.

Following the occupation and partition of France, millions of French people fled to the Free Zone in the South. This included large numbers of Jews, who began to try and reorganize their lives under German occupation and the Vichy regime. As time passed, the policies of the Vichy government became increasingly harsh. Throughout this period, the Jews were forced to cope with a new system of hostile laws, accompanied by unprecedented anti-Semitism that was encouraged by the government. In order to supervise the implementation of anti-Jewish actions and laws, Theodor Dannecker, an SS officer from Eichmann’s staff, was sent to France. He was given responsibility for anti-Semitic policy and reported to Eichmann’s office in Berlin. At the same time, the Vichy regime also initiated independent actions against the Jews. In July 1940, a law was enacted calling for an inspection of the naturalization of immigrants. In accordance with the law, some 16,000 immigrants, over one-third of whom were Jews, lost their citizenship. In addition, all persons who were not “French by birth” were expelled from the public administration and were forbidden to work as physicians or attorneys. Three months later, in October 1940, the Vichy regime published the Law on the Status of the Jews, which essentially reversed the emancipation granted to the Jews of France and defined Jewish status in accordance with a racial criterion. The Jews were subsequently denuded of their civil rights and their property, dismissed from the civil service, and expelled from their businesses. Tens of thousands of businesses and thousands of apartments were confiscated from Jews; Jewish physicians lost their titles. The goal of the law was to purify the civil service, the education system, the media, the cinema and theater, and the officer ranks of the military, ridding them of Jews. In the same month, numerous laws were published that further excluded the Jews from French society. These included the law for the “Aryanization” of Jewish property in the Occupied Zone. As noted, the main victims of anti-Jewish policy during this stage were foreign Jews, rather than those who held French citizenship. Thousands of Jewish migrants were placed in forced labor camps or detained in camps established throughout France.

Throughout the war, numerous concentration and incarceration camps operated in France, both in the Occupied Zone and in the zone under Vichy control. These camps formed the first link in the chain of deportation, bringing the country’s Jewish population to its death. The largest camps were situated in Southwest France and were established as early as 1939, serving for the incarceration of migrants and refugees. At the beginning of 1941, the population of the camps in the South reached a peak, with almost 40,000 Jewish prisoners alone. At first, the War Ministry was charged with the responsibility of overseeing the camps, but at the end of 1940 responsibility was transferred to the Ministry of the Interior. The formal guidelines for the management of the camps were reasonable, but in practice the living conditions were extremely harsh. The concentration camps were an initiative of the Vichy government, and the assistance provided by various aid organizations were part of the framework permitted by the authorities.

In January 1941, Dannecker established the Coordinating Committee of Relief Organizations in France. It brought together most of the Jewish relief bodies, both those that operated on behalf of French Jews and those operating on behalf of foreigners. In 1941, he also established two other important institutions. In March, the General Office for Jewish Affairs in France (the “Commissary”) was established, serving as the main body for coordinating anti-Jewish actions and legislation. This body, most of whose staff were anti-Semites, prepared the legislative infrastructure for the isolation of the Jews. Government ministries and even private businesspeople turned to the Commissary to seek guidance regarding their contacts with Jews. The staff of this body later engaged in systemic propaganda against Jews and participated in the process of “Aryanization.” Approximately sixth months later, in November 1941, after the relief organizations of Jewish migrants withdrew from the Coordinating Committee, Dannecker decided to form a compulsory central body for all the remaining Jewish bodies, with the exception of institutions included in the Consistoire., This was the background to the

founding of the General Union of Israelites of France – UGIF. From the German perspective, UGIF was intended to serve as a central and subordinate Jewish leadership along the lines of the Judenrat in Poland, with the goal of supervising the Jews’ activities and communal affairs. UGIF reflected both the German desire and the French interest in ensuring the presence of a national body responsible for all Jewish affairs, under the supervision of the Commissary – i.e. under government control. The establishment of this body encountered opposition both from the “Israélites,” who saw it as a further step in their exclusion from the French nation to which they fervently felt they belonged, and the Jewish migrants, who were extremely concerned that the body would be similar to those they had heard about in Eastern Europe, and moreover that it would be run solely by French Jews. In reality, UGIF did not fulfill the primary function intended by the Germans, but rather served as a large social assistance body. Although it was a single institution, in practice UGIF comprised two separate organizations. In the North, it was a centralized unit working with other migrant organizations that refused to cooperate with it and were established in opposition to the Consistoire. In the South, UGIF was solely a relief and social aid organization. Later, UGIF also worked underground and took part in the effort to rescue Jews, produce forged documents, and so forth.

From the summer of 1941, the French people began to show dissatisfaction with the Vichy regime and its collaboration with the German authorities. Despite expressions of disagreement, however, the Vichy government continued to strengthen its ties with Germany. To this end, even harsher laws were enacted against the Jews in the Occupied Zone, and hunts were organized for foreign Jews in Paris and the remainder of the zone. These Jews were sent to detention camps that had been established around the country. Pétain and his allies in government assumed that the Germans would be grateful for their actions against the Jews and thereby grant the French authorities greater powers over this field and others. This collaboration and the growing oppression by the Germans themselves led to a significant rise in rebel actions among groups with various political positions. Resistance movements also began to emerge among the French Jews during this period.

After some two years of persecutions and aggressive anti-Jewish legislation, the plans to deport the Jews of France to the camps in Eastern Europe began to be put into action (plans that had been discussed following the Wannsee Conference). Government employees were encouraged to do everything possible to help the Germans detain Jews, and the Germans prepared the groundwork for the deportations in the Occupied Zone. The first dispatch of Jews for extermination left in March 1942; in June, four trains departed for Auschwitz. Theodor Dannecker was charged with the responsibility of organizing the first deportations, and the first trains were filled with thousands of Jews who had been held in the camps in the Occupied Zone. Thousands of Jews immediately began to seek shelter from the Nazis and the French police, fleeing to the Free Zone or crossing the border into Switzerland.

On 16 July 1942, 4,500 French police officers launched a large-scale operation in Paris to arrest Jews with foreign citizenship, on the orders of the German authorities. The campaign lasted a week and ended with the detention of approximately 13,000 Jews at the Winter Velodrome, under conditions of extreme congestion, virtually without water, food, or sanitary facilities. The Jews were transferred from the stadium to concentration camps near Paris, and in July and August most of them were deported to Auschwitz, without their children. These actions, known as the “Vel’d’Hiv,” later became a symbol of the persecution of the Jews of France.

From the summer of 1942, the authorities began to deport Jews from the concentration camps to Auschwitz. The process began at camps in the Occupied Zone, such as Pithiviers, Beaune-la-Rolande, and of course Drancy, but later extended to camps in the Free Zone, including Gurs, Les Milles, and Rivesaltes. Campaigns and deportations were also undertaken during this period in various cities throughout France.

This period saw a change in France. For the first time, the deportations aroused substantial opposition to the Vichy regime among broad sections of the French public, since it was no longer possible to conceal the scale of the detentions and expulsions. Negative reactions began to be heard from members of the public. Many citizens reached out to provide help, whether by offering hiding places or by helping Jews cross the border into Switzerland. Public protests against the detention and deportation operations were also made by Church institutions in France, as archbishops and priests urged the faithful to help hide Jews, particularly children. The underground press also joined the wave of protests against the campaigns, responding on an unprecedented scale. The pressure of public opinion became an important political issue, eventually leading to a scaling back of the deportations as well as the organization of successful rescue operations. Accordingly, it can be concluded that, to some extent, the opposition restricted the implementation of the Final Solution in France, by comparison to the original plans.

At the same time, the Vichy regime was subjected to pressure from the opposite direction, from the German side, to meet the quotas for the deportation of French Jews. The persecution of Jews continued on the initiative of Heinz Rotke, who arrived in Paris to replace Dannecker as the official responsible for Jewish affairs in France. As a result of the oppression, most of the Jewish relief organizations that had hitherto acted to provide aid to Jews, both in the North and the South, went underground. Organizations such as Rue Amelot and OSE were transformed into Jewish rescue networks that worked to find hiding places for children, establishing children’s homes and hostels, preparing forged certificates and documents, and smuggling children across the border to Switzerland or Spain.

On 8 November 1942, the German forces took control of the South of France, and the entire country became a zone of German occupation. For reasons of bureaucratic convenience, the Germans left the French civil servants in their positions in the Free Zone, under their supervision. The Vichy government continued to be active and to exercise authority throughout the country, but only on the condition that it continue to serve German interests, particularly in the military sphere. The Germans demanded and received extensive assistance from the regime in order to implement their plans, but during this period an increasing number of French people refused to collaborate with the hunt for Jews. Following the German occupation, the situation of Jews throughout France deteriorated rapidly and the deportations to the East now included Jews with French citizenship, usually with the assistance of the Vichy government. These Jews had generally not been included in the deportee quota until this stage, but now the entire Jewish population of France, foreigners and citizens alike, were subject to deportation to the East. For most of the French public, the Vichy regime came to be seen as a puppet government acting under the German occupiers. At the same time, the French Resistance became a significant and broad-based movement whose members – Jews and non-Jews alike – engaged in armed underground activities and rescue operations.

In June 1943, Alois Brunner, an officer from Eichmann’s unit, was sent to Paris to help accelerate the deportation of Jews from France. The SS assumed full control of Drancy, which acquired the exact same status as any other concentration camp established by the Germans.

The Vichy government, which had become an arm of German rule and implemented its orders, introduced an extensive system of anti-Jewish legislation that lasted until the end of German rule. The deportation of Jews continued until France was liberated by the Allies in August 1944.

The German goal was to annihilate the entire Jewish population of France, along with that of Europe as a whole. However, relative to other countries, the percentage of French Jews who survived was high: approximately three-fourths of the Jewish population survived, thanks mainly to the rescue operations and to the pressure of public opinion. Approximately one-fourth perished, mainly due to French collaboration with German decisions.

Based on:

- The History of the Holocaust – France, Asher Cohen (ed.), Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1996 (Hebrew).

- Being a Jew in France, 1939-1945, Renée Poznansky, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem (Hebrew).