- Emmanuel Ringelblum, Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto, The Journal of Emmanuel Ringelblum, Jacob Sloan, ed. and transl., New York: Schocken Paperback, 1974, pp. 273-274.

- Ibid., pp. 273-274.

- See the comprehensive article by Lenore J. Weitzman in Jewish Women’s Archive.

- This order was given by Reinhard Heydrich, on September 21, 1939.

- Bronka Klibanski, In the Ghetto and in the Resistance: A Personal Narrative, in Dalia Ofer and Lenore J. Weitzman, eds., Women in the Holocaust, New York and London: Yale University Press, 1998, p. 186.

- Havka Folman Raban, They Are Still With Me, originally published in Hebrew as Lo Nifradeti Mehem, Israel: The Ghetto Fighters’ Museum, 1997, p. 67.

- Ibid., p. 85.

- Zivia Lubetkin, In the Days of Destruction and Revolt, Israel: The Ghetto Fighter's House, 1981, p. 43.

- This agreement, signed by the German and Russian foreign ministers in August of 1939, was a non-aggression pact between the two countries. It contained a secret annex that divided Poland between Germany and Russia. Germany breached the agreement and invaded Soviet-held territory on June 22, 1941.

- Antek Zuckerman, A Surplus of Memory: Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993, p. 156.

- Vladka Meed, On Both Sides of the Wall, Israel: The Ghetto Fighters’ House, 1973, p. 120-121.

- Gary Scott Glassman, The Couriers of the Jewish Underground in Poland During the Holocaust, available online.

- Havka Folman Raban, p. 82.

- Adina Blady Szwajger, I Remember Nothing More, New York: Pantheon Books, 1988, p. 82.

- Vladka Meed, p. 129.

- Adina Blady Szwajger, p.105-106.

- Ibid., p. 108.

- Ibid., p. 111.

- Gusta Davidson Draenger, Justyna's Narrative, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996, p. 52-53.

Introduction

The story of the female couriers of Nazi-occupied Europe is a story of resistance that has largely remained in the shadows, or perhaps been overshadowed by the stories of armed resistance in the ghettos of Europe. Yet it is a story of incredible bravery exhibited by a group of Jewish girls – some as young as fifteen years old – and women in their late teens and early twenties. These girls braved danger and death in order to serve as the lifeline between Jewish communities throughout war-torn Europe. Disguised as non-Jews, they transported documents, papers, money and ultimately also ammunition and weapons across borders and into ghettos. They wrote “a glorious page in the history of Jewry”1, one which, according to Emanuel Ringelblum, deserves to be immortalized. As he wrote in a diary entry in May of 1942:

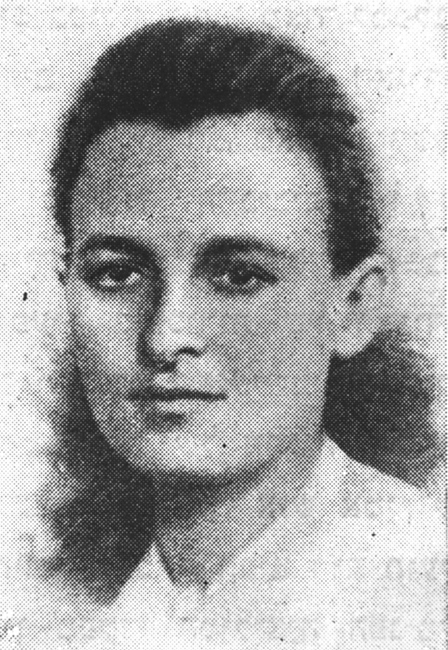

“These heroic girls, Chajke and Frumke - they are a theme that calls for the pen of a great writer. Boldly they travel back and forth through the cities and towns of Poland. [...] They are in mortal danger every day. They rely entirely on their ‘Aryan’ faces and on the peasant kerchiefs that cover their heads. Without a murmur, without a moment of hesitation, they accept and carry out the most dangerous missions. Is someone needed to Vilna, Bialystok, Lemberg, Kowel, Lublin, Czestochowa, or Radom to smuggle in contraband such as illegal publications, goods, money? The girls volunteer as thought it were the most natural thing in the world. ...They undertake the mission. Nothing stands in their way. Nothing deters them. [...] How many times have they looked death in the eyes? How many times have they been arrested and searched? [...] The story of the Jewish woman will be a glorious page in the history of Jewry during the present war. And the Chajkes and Frumkes will be the leading figures in this story. For these girls are indefatigable.”2

The word “courier” does not do these women justice. They were much more than messengers. True, they carried mail and information back and forth from place to place. True, also, they smuggled forged identity cards, documents, underground newspapers and money into the sealed-off ghettos of Nazi Europe. However, they were also the first to smuggle guns, grenades, ammunition and other weapons into many of the ghettos. And in addition to the strictly “messenger” part of their job, these girls who risked their lives to move from ghetto to ghetto also served a very human purpose – they inspired and brought hope, along with information, to Jews who would otherwise have been cut off from the entire world, as if to reassure them that they had not been forgotten. In the dark days of Europe during the holocaust, they were lifelines that connected Jewish communities and isolated ghettos to each other and to the outside world. As such, in this article, as in others3, we will refer to these intrepid girls as “kashariyot”, from the Hebrew word “kesher”, which means connection. This article attempts to pay homage, in some small way, to the kashariyot.

The Need for the Kashariyot

One of the first things the Germans did when they initiated World War II, even before Poland had capitulated to the blitzkrieg of the Wehrmacht, was to decree that all Jews in occupied territories be concentrated into ghettos.4 These ghettos were to be located near railway lines. They were to be closed off, with limited entry and exit. They were to be isolated. Although most historians agree that at this early date the Nazis had not yet crystallized their plan for the “Final Solution” of the Jewish question, there were definite reasons for the ghettoization of the Jews by the Nazis. Ghettoization was a means to separate the Jews from other peoples in occupied territories. It allowed the Germans to control the Jews efficiently. And it physically condensed them in preparation for a future arrangement.

Each ghetto was different in its internal policies and governance as well as in its external segregation: some were loosely guarded while others were almost hermetically sealed; some were enclosed by high walls while others were surrounded by fences. However, each ghetto was isolated and cut off from the world around it. Travel by train was prohibited for Jews. Mail was censored. Radios were forbidden. This was all part of the German plan. Sealed inside their ghettos, Jewish political parties, youth movements and other organizations in different cities could no longer keep up their contacts. There was no way to know what was happening on the other side of the ghetto gate.

The Jews needed to find some way to reach the outside world and communicate with each other. Out of this need, the courier system was born. Youth movements were the first to send their members across borders to reach other ghettos. However, it became increasingly dangerous for Jews to be found outside their ghettos – the Germans, early on, began to impose the death penalty on anyone so found. At this stage, the Jews trapped in their ghettos began more and more to rely on women as kashariyot. This occurred for a number of reasons. First and foremost, a Jewish man could easily be identified as such – he had only to be ordered to drop his pants and the telltale sign of his circumcision would give him away. In addition, men who were out and about on the streets generated suspicion – why weren’t they at work? It was much easier for women to stroll the streets, seemingly carefree, on the way to a lunch date with friends, or casually shopping. Women were also more likely to speak the local language; for instance, many women had been educated in Polish secular schools, while the boys had undergone mostly religious instruction in heder. The girls, therefore, spoke Polish fluently, without an accent or a Jewish inflection that could give them away, and felt more at home on the Polish street. An additional reason why girls and women made excellent kashariyot was their intuition. Bronka Klibanski, a courier who connected the ghettos in the area of Bialystok and Grodno in Poland, wrote, “In comparison to men, it seems to me that we women were more loyal to the cause, more sensitive to our surroundings, wiser – or perhaps more generously endowed with intuition…”5 This intuition helped them to sense when someone on the street was staring at them a little too long, when someone could be trusted, when a contact was actually a Nazi collaborator, and when to cut and run.

The Functions of the Kashariyot

At the very beginning, when the Germans were first creating ghettos in which to isolate the Jews, the kashariyots’ primary functions were to reconnect the Jewish communities, political parties and youth movements. As such, logically, most of the couriers came from, and were called into service by, the youth movements for which they had such passion and loyalty. Many were willing to do anything for the cause of their movements. In this stage, they reconnected Jewish communities by bringing information, news and written bulletins from one ghetto to another. Havka Folman Raban, a courier for the Dror movement who was ultimately captured and imprisoned in Auschwitz, writes,

“It should be remembered that one of the Germans’ goals was to isolate the Jews, cut them off from each other. The purpose of the trips by couriers like myself, was to meet with our [Dror] people, maintain contact, hand over bulletins and other movement publications and to tell them what was happening in the center and the various branches. Sixteen and a half, seventeen year old me was expected to transmit information about an active center, about ideas on resistance, report that there was still a movement, that not everyone was depressed…”6

No less important was the function of the kashariyot as beacons of hope in those very dark days. They gave advice, they encouraged the Jews not to give up, they united and inspired people by bringing news of their families or their communities. Members of their movements from other cities rejoiced when the girls appeared. As Havka wrote,

“One of the most difficult concerns that filled the hearts of Jews was the feeling that the entire world had forgotten about us, that we had no hope and certainly no future; this was loneliness and all its horror. With meager abilities, we young women worked to ease this feeling of loneliness, so that it would be less suffocation. We let them know they could depend on contact and activity.”7

Frumka Plotnicka, a leader of the Hehalutz youth movement who was one of the most traveled couriers, was nicknamed “Die Mameh”, Yiddish for “the mama”. When she arrived in a community:

“Jews would flock around her from all sides. One would ask her if he should return home or continue his way eastward to the Soviet-dominated provinces. Another would come in search of a hot meal or a loaf of bread for his wife and children. They called her 'Die Mameh' and indeed she was a devoted mother to them all.”8

Once the Germans began to exterminate the Jews, however, the role of the kashariyot changed. The extermination policy was launched by the Einsatzgruppen, the mobile killing units that entered Soviet territories right behind the Wehrmacht, as it fought its way into Russia after Germany breached the Ribbentrop-Molotov agreement.9 At this point, in the fall of 1941, the Germans had decided upon the “Final Solution” to the Jewish question. However, the Jews did not yet recognize that the Germans’ intention was to destroy the entire Jewish nation. A key role was played by the kashariyot, who spread the word about the killing units and the shooting operations. It was the information spread by the kashariyot that enabled Jewish leaders in farflung places and in different communities to put the pieces of the puzzle together and to realize that the German plan was not merely to massacre Jews in certain locations, but to kill all the Jews of Europe.

Now the kashariyot took on yet another role – once they had seen what was in store, they had to warn communities where slaughter had not yet occurred, so that they could take some action. These young girls found themselves having to detail the mass murders. They were witnesses. Frumka Plotnicka saw the destruction of many Jewish communities. She witnessed Jews being loaded into cattlecars and deported to death camps. She reported the annihiliation of so many Jewish towns and ghettos that she began to refer to herself as "the gravedigger of the Jewish people."10

Hand in hand with the role of warning the Jews that they were standing at the edge of an abyss came the task of assisting the Jews in mounting armed resistance against the Germans, once the youth movements in the ghettos had decided to do so. The kashariyot put their lives at risk and smuggled guns and ammunition into the ghettos. Vladka Meed, a courier who worked on the Aryan side of Warsaw for the Bund, wrote,

“The major problem on both sides of the wall was getting weapons, weapons with which to resist the Germans. […] Deep in every heart, bringing us ever closer together, lay the yearning for vengeance, vengeance for our families taken to the death camps, for the wrongs and sufferings we ourselves had borne. […] It was a great event for me when I managed to procure my first revolver.”11

This was no small feat: it was very difficult to get weapons to the Jews in their sealed ghettos. Frumka was the first courier to smuggle weapons into the Warsaw ghetto – she brought them in at the bottom of a sack of potatoes.12 Havka relates that she and Tema Schneiderman, another of the incredibly courageous kashariyot, smuggled grenades into the Warsaw ghetto by hiding the grenades in their underwear. As they rode through Warsaw in a streetcar, Tema asked her, “what would happen if a gentleman invited us to sit beside him?”13 The loud laughter of the girls covered the fear they felt. Adina Blady Szwajger, a young doctor who also served as a courier in Warsaw, had a close call when she was stopped by a patrol on Zelazna Street and was ordered to open her bag. Only her broad smile and the cocky way she opened her bag wide saved her; the German gendarme who had stopped her never suspected that she was carrying ammunition under the potatoes in her bag.14 Vladka Meed told of having to quickly repack a carton of dynamite into smaller packages in order to pass it into the ghetto through the grate of a factory window. As she and the gentile watchman, who had been bribed, worked frantically in the dark, the watchman trembled like a leaf. When they finally finished, the watchman “stood there flushed, drenched in perspiration and unnerved. […] ‘I’ll never risk it again,’ the watchman mumbled. ‘I was scared to death.’”15

In parallel with smuggling weapons into the ghettos, the couriers also helped smuggle Jews out of the ghetto. Both these missions were of the utmost urgency. Both were attempts at resistance, however different. In many cases, helping people leave the ghetto was the only way to save lives. Yet living on the Aryan side of a city was fraught with difficulty. Apartments needed to be found, false documents, including identity cards, had to be obtained, money had to be supplied to support people who could no longer work because they did not dare show their Jewish faces in public. Adina Blady Szwajger described the huge weight on her shoulders that she felt the first few days of every month when she had to walk around with piles of money in order to distribute them:

“Every pile was the only means of support for fifty to a hundred people for a month. Whereas for me these piles of somebody else’s money were just pieces of paper. Dangerous pieces of paper at that. ...We had to get rid of these pieces of paper as soon as possible, because they might cost us our lives.”16

The mission of saving lives was hazardous and complicated. Adina wrote,

“Apart from giving out money, we had lots of other things to do. We had to visit people and arrange things for them, to go and see our own families so that they did not feel isolated, or to help those who found themselves in difficult situations. We had constant problems with lodgings and papers. Every so often somebody would be betrayed, or ‘burned’ as we called it, and we had to move them to new lodgings.”17

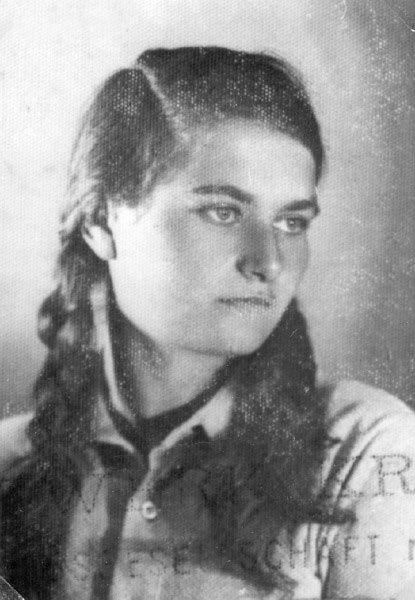

In performing their missions, the kashariyot had very little to rely on, other than forged papers and “good” looks – meaning facial features that didn’t give them away as Jews. Some of the couriers bleached their hair blonde; others, including Frumka Plotnicka, had to be convinced to wear makeup to disguise their features. Not all were blonde-haired or blue-eyed. Yet there was one trait that all the couriers required in order to succeed. They all had to have incredible poise and nerves of steel to get them through checkpoints, over borders, into and out of ghettos, and around Europe with illegal documents, weapons and other contraband – in other words, to take the risks they took every day. It would be an understatement to say that the missions of these women were fraught with constant danger. Many of the kashariyot lost their lives trying to fulfill their assignments. For instance, two of the three couriers in an iconic photograph, taken of the three at a Gestapo Christmas party in Grodno in 1941, were captured and sent to Auschwitz where Lonka Kozibrodska died in the arms of Bela Hazan. Tema Schneiderman was killed at the Treblinka death camp.

“And that is what everyday life was like: people, problems, forever running around – and fear. Already then there was fear. Every familiar face was hostile. The whole town, my own town, that I had grown up in, was strange, hostile, and every corner I turned might be my last.”18

It is hard for us, decades later, to appreciate the constant fear and danger in which these young girls lived, worked and operated. Gusta Davidson Draenger, a courier in Krakow known by her Polish alias “Justyna”, wrote a diary from her prison cell after being captured by the Gestapo. In her diary, written at great risk on sheets of toilet paper smuggled into her cell, she described the perils faced by anyone trying to pass as a non-Jew.

“You would reveal your Jewishness in a thousand small ways; every anxiety-filled move; every step taken with a back hunched over from the yoke of slavery; every glance that bespoke the terror of a hunted animal; the entire form, the face on which the ghetto had left its indelible mark. You were nothing more than a Jew, not only because of the color of your eyes, hair, skin, the shape of your nose, the many telltale signs of your race. You were simply and unmistakably a Jew because of your lack of self-assurance, your way of expressing ourself, your behavior, and God knows what else. You were simply and conspicuously a Jew because everybody outside the ghetto strained to detect your Jewishness, all those people eager to do you harm, who couldn’t abide the thought that you might be cheating death. At your every step they would look straight into your eyes – impudently, suspiciously, challengingly – until you would become entirely confused, turn beet red, lower your eyes – and thus show yourself to be undeniably a Jew.”19

Conclusion

The kashariyot were no more and no less than young Jewish girls, many barely out of their teens, caught in the horror of Nazi-occupied Europe. They showed exceptional loyalty to their movements, and to their people. With unfathomable bravery, they faced incredible dangers every minute of every day, and yet somehow found the strength to continue with their missions, or to die trying. They are icons of heroism, and they shatter many stereotypes: that the Jews went to their deaths like sheep to the slaughter, that women are less capable than men of resistance. Despite all this, the glorious page of history which is their due has not yet been fully written. It should be. In light of their achievements and their exploits in the nightmare of the Holocaust, we can only be in awe of them.