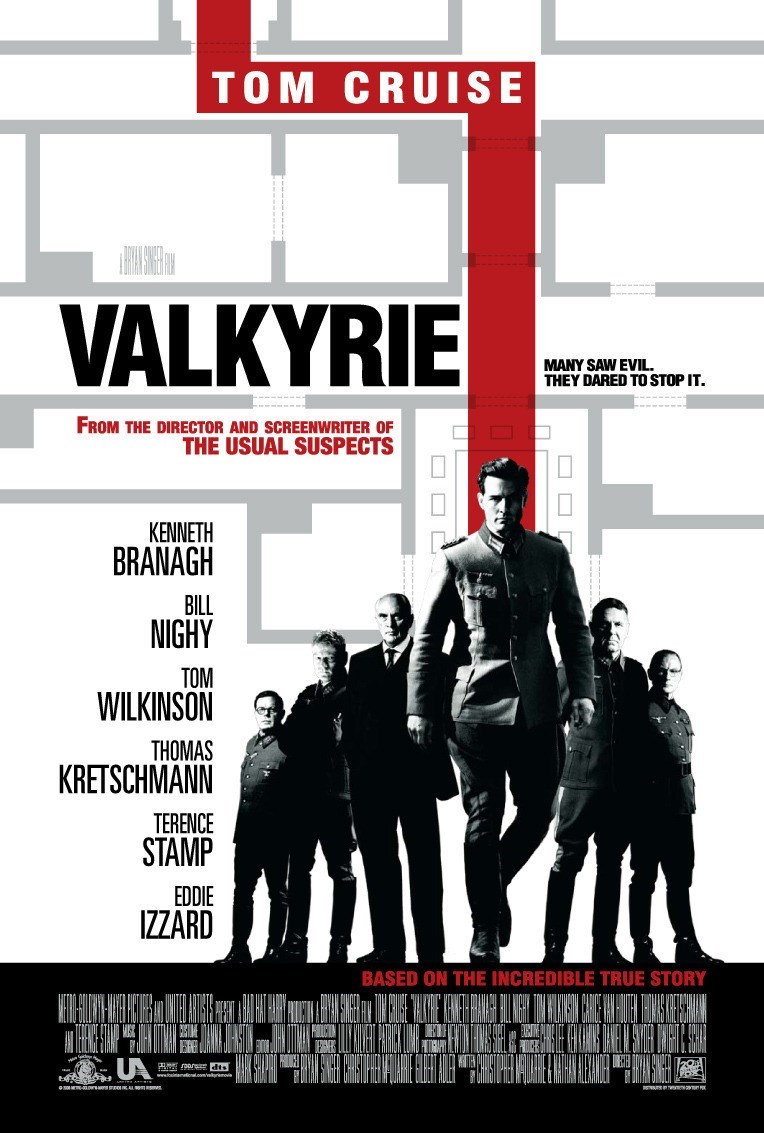

"Valkyrie" - Movie Poster

"Valkyrie"

Director: Bryan Singer

USA-Germany, 2008/ English and German / 121 minutes

Valkyrie, the 2008 film directed by Bryan Singer, is a deftly executed historical thriller that succeeds in faithfully depicting an attempt to assassinate Adolf Hitler and implement a coup of the German government. Focused almost exclusively around the conspirators and the events of July 20th, 1944, the movie condenses or glosses over background and motivation, as dramatic movies must, to maintain the forward momentum of the story. This article will attempt to illuminate some of the subtext that can complement discussions of Valkyrie by using the film as a lens through which we can view history.

The opening of the film establishes some historical context and the tone of the story. The title “Walküre” appears in German and morphs into the English title “Valkyrie.” Against a Nazi flag we read the text of the “Hitler oath,” swearing German soldiers’ unconditional obedience to Adolf Hitler. A voiceover by the central character, Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg (Tom Cruise), begins in German and changes into Cruise’s American-accented English. From this point forward, all the dialogue will be in English. Some viewers found the language distracting (most of the actors use their natural British accent) but this Hollywood film made the right choices to appeal to the widest possible audiences.

It is April of 1943. Stationed in Tunisia, Stauffenberg writes in his journal, “The Führer’s promises of peace and prosperity have fallen by the wayside leaving in their wake a path of destruction. The outrages committed by Hitler’s SS are a stain on the honor of the German army. There is widespread disgust in the officer corps toward the crimes committed by the Nazis, the murder of civilians, the torture and starvation of prisoners, the mass execution of Jews. My duty as an officer is no longer to save my country, but to save human lives. I cannot find one general in a position to confront Hitler with the courage to do it.”

Stauffenberg directs some adjustments to the desert operation to bring home the German soldiers safely, and is strafed by aircraft fire, resulting in the loss of an eye, a lower arm, and some fingers. The movie implies that Stauffenberg’s motivation for joining the conspiracy lie not in the fact that he was injured while serving, which would be a personal revenge, but in his own moral code (duty to Germany and humanity, not to Hitler). It should be noted that Stauffenberg did not actually witness the atrocities of the Holocaust, except the starvation of Russian prisoners of war; his fictionalized journal entry adequately conveys his moral outrage and his position in the war effort. It is difficult to pinpoint his motives in the historical record, but the character in the film acts decisively in a heroic manner.

German resistance to Nazi policy through 1938 consisted of disparate groups of varying ideologies, who rarely made contact with each other. They succeeded mostly symbolically or with modest triumphs such as the clandestine endeavors of underground networks and individuals later recognized as Righteous Among the Nations. There were fifteen attempts to assassinate Adolf Hitler from 1939 until his suicide in 1945. The events portrayed in Valkyrie in 1944 are the final concerted efforts of the group most likely to achieve a complete upheaval of government: high-ranking officials from the Wehrmacht (Armed Forces), the Foreign Office, and the Abwehr (Military Intelligence) who orchestrated their opposition to the regime from within the German state apparatus.

After a few unsuccessful attempts, Colonel Hans Oster rebuilt the secret resistance network from within his Office of Military Intelligence. General Friedrich Olbricht, head of the Army General Office, and General Tresckow (Kenneth Branagh) fail to blow up an airplane with Hitler on board (as depicted in the movie), and Tresckow recruits the willing Stauffenberg to lead the plot to assassinate the Führer.

Eliminating Hitler would hopefully allow the conspirators to negotiate better truce terms with the Allies. By 1944, the resistance group is at the height of its potential power, but they know that time is running out. The conditions are ripe for a coup, but it is no easy task. The German army’s victories in Czechoslovakia and France, and Hitler’s ensuing popularity with the German people made it more difficult to remove him from power. When the United States entered the war (December, 1941) as Russian territory was being invaded, many officers felt that Germany would ultimately lose, but how could the war end without the Soviets gaining control of Europe? These are just a few of the complications that the secret resistance had to contend with; Stauffenberg in the film is surprised to learn that the conspirators have not readied a post-assassination political plan for a new government, even at that late stage.

Stauffenberg was the right man for the job; his strategies, direct approaches, and resolve moved the conspirators forward from philosophy into their final play (and dramatically drive the film’s plot forward toward the third act). The central portion of the film involves various discussions and maneuverings: Who can be trusted? How can the mission be pulled off? Who is willing to sacrifice their life and their families for Germany? Some history is alluded to by the presence of central personalities at meetings of the resistance, but students will only go deeper than the film’s surface by researching the fascinating biographies and careers of these real-life spies, war heroes, and traitors. One conspirator portrayed in the film, Carl Goerdeler, seems to be a composite of his historical personage and some Catholic resistance members who objected to the murder of Hitler on ethical grounds. The movie conveys an atmosphere of deadly secrets and paranoia; the music perhaps overemphasizes feelings of dread and disgust when the character of Adolf Hitler is on the screen.

Stauffenberg transported a briefcase bomb into a bunker where Hitler and his staff were meeting. The bomb exploded, and Stauffenberg, believing that Hitler was dead, mobilized everyone at his command to implement Operation Valkyrie, which would allow the civilian army (controlled by the conspirators) to wrest control of the government from the other executive departments and armed forces. Ludwig Beck’s (Terence Stamp) ominous warning proves itself: “This is a military operation. Nothing ever goes according to plan.”

Time was wasted since the explosion, communications were spotty at crucial moments, and hours later the truth was out: Hitler was alive and the conspirators were to be arrested. A few of the plotters, including Stauffenberg, were rounded up and executed by firing squad. Stauffenberg’s assistant valiantly tries to block the shooters but is gunned down as well. Arrests, executions, and show trials of German civilians continued for months afterward until Hitler finally brought down his regime by committing suicide. Even General Erwin Rommel, who may have been partial to the resistance, was persuaded to secretly commit suicide and receive a state military funeral rather than face the indignity of rank-stripping accusations.

The conspiracy failed but it was daring nonetheless. As Tresckow states, “We have to show the world that not all of us are like him. Otherwise, this will always be Hitler's Germany.” There is no room in the movie to discuss the movements of history after the denouement of the story, but it can lead to interesting discussions in the classroom. The conspirators were at first neglected in postwar Germany’s collective consciousness, or even thought of as traitors, but the governments that followed eventually “rediscovered” their past and vaunted the fallen plotters’ status. Today, one can visit memorials, museums, and statues in honor of their resistance, which is now viewed as a noble and ethical foundation of a democratic state.

How “ethical” were the conspirators? Should they be considered “heroes”? Questions about the characters’ morals can lead to dialogues about dilemmas — a key topic when addressing the Holocaust or genocide. Valkyrie presents Nazi officers as the main characters in a setting in which unprecedented large-scale mass murder is only mentioned briefly in Stauffenberg’s voiceover at the beginning of the film; the Holocaust is in the background. The conspirators are clearly part of the Nazi regime, with knowledge about SS war crimes (to say the least), but their portrayal (in the film and in history) make them something less than perpetrators while their actions make them something more than bystanders. That moral gray area is fascinating to discuss, and the filmmakers either ignore it or expect audiences to glean more from Tom Cruise’s performance than perhaps he could deliver in the film’s theatrical cut. It is interesting to compare Valkyrie with Schindler’s List in terms of presentation of the Holocaust, heroic motivation, and specific scenes grounded in emotion. Spielberg’s film contains moments of quiet power in which we can feel Schindler’s emotions roiling and moral compass fluctuating; see our study guide for details.

Valkyrie may also be used in high school classrooms to engage students in the subject of German resistance, or at least interest them by dramatizing the climactic event in a history full of intrigue and “what if” exercises. The film contains only a handful of obscene words to which educators may object. Teachers should be prepared to delve into questions of Stauffenberg’s motivation and his aristocratic background. Some see him as a mythical hero; others see him as representative of outdated political philosophies. Students may wish to research and debate the issue of what kind of Germany the conspirators wished for after the coup. Academic studies of German resistance are only now gaining wider recognition after the movie’s success, and the subject contains multitudes of aspects to consider.

Bibliography

- Boeselager, Philipp von. Valkyrie: the Plot to Kill Hitler. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson. 2008. A personal memoir by one of the conspirators.

- Fest, Joachim. Plotting Hitler's Death: The Story of German Resistance. Holt Paperbacks. 1997. ISBN 978-080-505648-8

- Galante, Pierre. Operation Valkyrie. Harper and Row, 1981, ISBN 0060380020.

- Gisevius, Hans Bernd, Valkyrie: An Insider's Account of the Plot to Kill Hitler, 2009 reprint of one volume abridgement of two volume text, To the Bitter End, 1947. Foreword by Allen Welsh Dulles, introduction by Peter Hoffmann. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston; Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA ISBN 978-0-306-81771-7

- Hoffmann, Peter. The History of the German Resistance, 1933–1945. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-77-3515313

- Jones, Nigel. Countdown to Valkyrie: The July Plot to Assassinate Hitler. Frontline, 2009.

- Moorhouse, Roger. Killing Hitler, Jonathan Cape, 2006. ISBN 0-224-07121-1

- Pemberton, Jacob. "20 Juli: The Politics of a Coup". From Ex Post Facto, Journal of the History Students at San Fransisco State University. Volume XI, 2002.