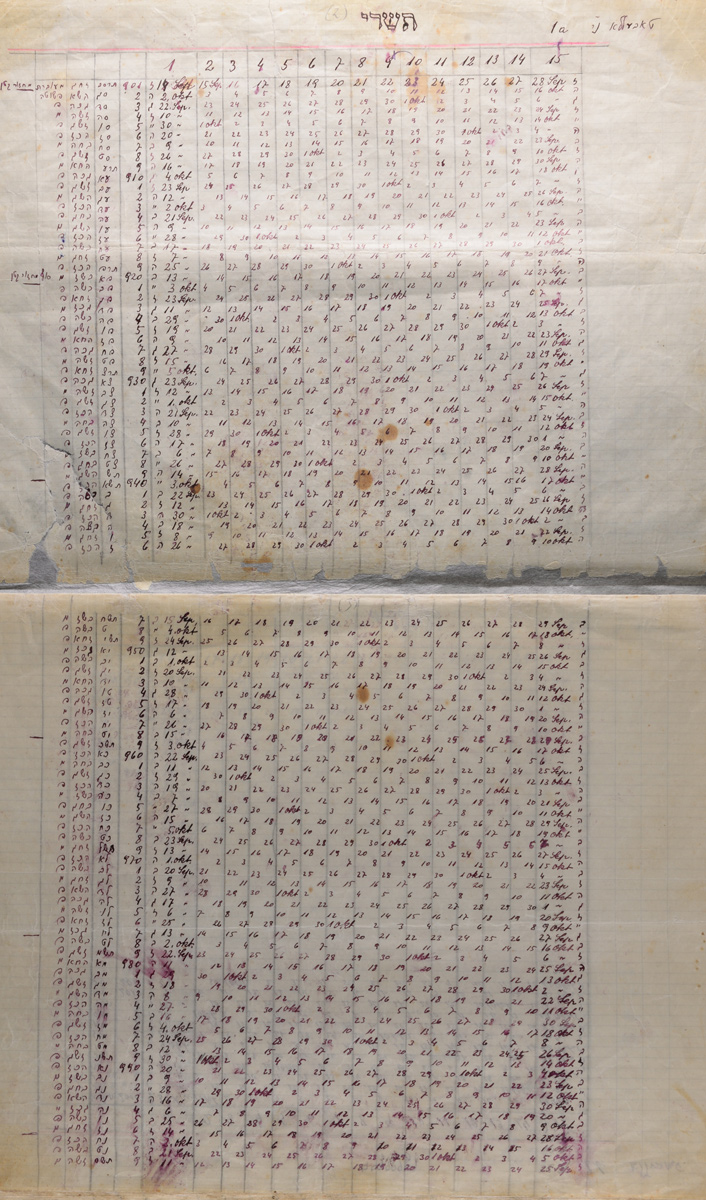

Hebrew calendar drawn up by Moshe Menachem Herstik in the Ilia camp, southern Transylvania, Romania

Moshe Menachem and Rachel Herstik lived in the town of Lupeni in southern Transnistria, Romania, with their nine children: Mordechai (a Yeshiva student who succumbed to pneumonia before the war), Alexander-Sender, Shlomo, Raizel, Shalom, Yehuda (died in infancy), Yehezkel, Zehava and Shmuel Yosef. Moshe made a living in trade, but his business suffered as a result of the economic slump of the late '20s and early '30s. The family maintained a Hasidic Jewish lifestyle, and had Zionist leanings. Moshe wanted to immigrate with his family to Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine), but his financial situation prevented him from doing so.

In July 1941, the Herstiks were deported from Lupeni, leaving all their belongings behind. They were confined in the Nalacz camp, located in an abandoned castle, and transferred to the Sacel camp several weeks later. In December, they were marched to the Ilia camp. Two of Moshe and Rachel's sons were conscripted to forced labor camps: Alexander to a camp in Transnistria and Shlomo to a camp in southern Transylvania.

At Ilia, Moshe managed to establish a synagogue and study room for children in one of the camp rooms, so that children and teenagers wouldn't wander around with nothing to do while the adults left for forced labor in the area. Moshe decided to draw up a Hebrew calendar from memory, for the use of the Jews incarcerated there. Yehezkel, 11 years old when he arrived at Ilia, recalls in his testimony that camp inmates wanted to celebrate their son's Bar Mitzvahs on the Hebrew date rather than the Gregorian date, and to arrange memorial services for their loved ones who had perished or been murdered. Moshe ran study sessions and even prepared a Purim play with his pupils. His family lived adjacent to the synagogue and Heder (Hebrew school).

Shlomo escaped from the labor camp and reached Bucharest, where he became active in Zionist circles. Alexander also managed to escape, and joined Shlomo in Bucharest. Shlomo arranged a "Certificate" (immigration permit) to Eretz Israel for Alexander, and in 1944, Alexander boarded the "Mefkure" en route to Eretz Israel together with some 300 Ma'apilim (illegal immigrants). On 5 August, the ship was bombarded, seemingly by a German submarine, and sank. All but five of the passengers drowned, including Alexander.

The Ilia camp was liberated by the Red Army in October 1944. The Herstiks moved to Arad, and immigrated to Israel in 1948. Moshe kept the Hebrew calendar he had compiled until the day he died. When the pages began to disintegrate, Moshe's son Yehezkel decided to donate them to Yad Vashem as part of the "Gathering the Fragments" project.

Reconstructing a calendar from memory requires effort and a great deal of prior knowledge, and under these circumstances, was potentially life-threatening. The determination to know the date each day, to mark the Sabbath and Jewish festivals, to be in essence a master of his own time, enabled Moshe Herstik to preserve his humanity and his Jewish spirit.