Shmerke Kaczerginski and the Recordings for the Jewish Historical Commission

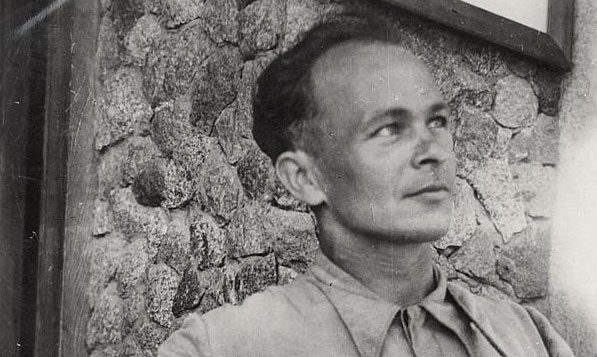

Shmaryahu (Shmerke) Kaczerginski was born on October 28, 1908 in Vilna. His parents died during the early months of the First World War, and Shmerke (then 6 years old) and his brother Yankl were raised by their grandfather. Kaczerginski was educated in Vilna’s Talmud Torah for needy Jewish children with Yiddish as the main language of instruction. After completing his primary education, he began taking high school classes at night and worked during the day at a lithograph studio where he met with leaders of radical political movements and joined the communist youth movement.

Shmerke became a radical political activist and began to publish articles in the local newspapers, and also wrote songs such as “Tates mames kinderlakh” (Fathers, Mothers Children), viewed as a song calling for social revolt.

In 1929 Kaczerginski joined the literary and artistic group Yung Vilne (Young Vilna) that expressed the mood of Vilna’s Jewish society. Among them were the poet Abraham Sutzkever (b. 1913), the author Chaim Grade, and others. Kaczerginski became very popular.

The Soviet Army conquered Vilna in September 1939, but after a few weeks transferred the city to the Lithuanians, and Vilna became the capital of Lithuania. Kaczerginski left Vilna and continued his work as a writer and teacher in Bialystok. When in 1940 the Red Army troops again entered Vilna, Kaczerginski returned to Vilna. Under the Soviet regime he witnessed the Stalinist censorship and shuttering of Jewish culture and protested. In June 1941 Germany invaded the Baltic States. Kaczerginski first posed as a deaf-mute in order to avoid deportation to the ghetto, but in early 1942 he was sent to the Vilna ghetto.

In the ghetto he continued his resistance activities: writing songs to console and encourage the ghetto inhabitants, and planning other forms of resistance. As a cultural organizer and artist he took part in organizing the theatrical productions, literary evenings and educational programs. He married Barbara Kaufman in the ghetto, who perished in April 1943.

Many of the songs he wrote in the ghetto became instant hits like the tango “Friling” (Spring-time), written after his wife’s death, “Shtiler Shtiler” (Quiet Quiet), a testimony and response to the mass murder site Ponar, a forest near Vilna, and “Yugnt Himn” (Youth Hymn), which was adopted as the anthem of the ghetto youth club.

In March 1942, when the Nazi’s began to confiscate Jewish cultural works, Kaczerginski, Sutzkever and others smuggled cultural artifacts from the Aryan side of Vilna to the ghetto. In addition, he was an active in Vilna’s partisan movement, the Fareynike Partizaner Organizatsye (United Partisan Organization, FPO).

Throughout this period he continued to write new songs on various themes of ghetto life: “Dos elente kind” (The Lonely Child), inspired by the story of a Jewish girl adopted by the family’s Christian housekeeper; “Mariko” (Mary), a lullaby for a woman who suddenly disappeared; “Itsik Vitnberg”, a song telling of the self-sacrifice of the leader of the partisans in the Vilna ghetto.

Kaczerginski, like other writers and composers of the period, sensed that he must document the history of the ghetto and the lives of the heroes and other inhabitants of the ghetto. He portrayed the lives of both the victims and survivors of the ghetto, in order to leave behind a testimony of this dark period in Jewish history.

Following the unsuccessful uprising of September 1943 and the death of Itsik Vitnberg, Kaczerginski fled the ghetto with other members of the partisan movement. While living in the forest he continued to write songs, such as the “Partizaner-Marsh” (Partisans’ March) and “Yid, du partizaner” (The Jewish Partisan). He also wrote the song “Warsaw”, marking the anniversary f the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

Already in the forest Kaczerginski began to document the songs he had written and heard as well as the stories he had been told. In August 1944 Kaczerginski was liberated by Soviet forces and soon afterwards began to locate and rescue Jewish books, art, and other cultural artifacts. Along with his colleagues he established a Jewish museum in Vilna. Immediately after the war Kaczerginski sought to publish his songs and the testimonies he had heard but was unsuccessful. He traveled to Lodz, where he worked for the Jewish Historical Commission, which was collecting testimonies of survivors. He edited the book “Undzer Gezang” (Our Song) in 1947, the first anthology of Jewish songs published in post-war Poland.

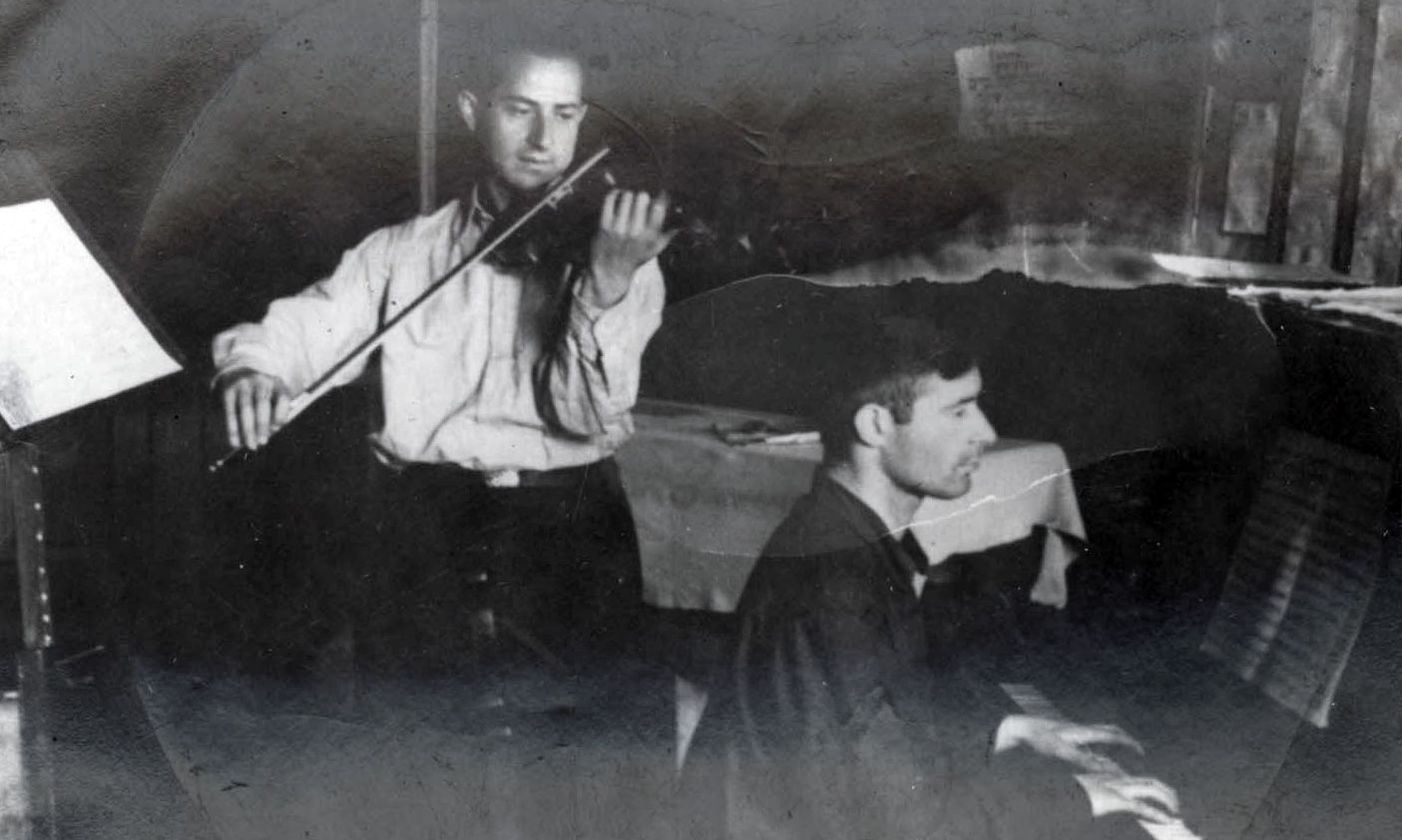

Since he lacked formal musical training, Kaczerginski’s would memorize the melodies and later sing them back to someone able to notate them. In Lodz he found the musicians Leon Wajner and David Botvinik, who notated music for him and set some of his songs to music. Wajner composed the music for his song “Warsaw” and Botvinik the music for his “Khalutsim” (Pioneers).

Kaczerginski devoted his spare time to helping the Jewish children of Lodz. He organized for them a commemorative program on the Nazi ordeal and Jewish resistance that left a strong impact on these young children. Kaczerginski married again in Lodz. With the rise of anti-Semitism, particularly after the Kielce pogrom of July 1946, Kaczerginski decided to leave Poland and moved to Paris, France.

In November 1947, Kaczerginski traveled throughout the American zone in occupied Germany and visited seventeen displaced persons camps. He lectured to survivors, gathered new materials of folklore and culture, and recorded songs sung by Holocaust survivors. These recordings were presented to the Central Jewish Historical Commission (CHC) in Munich. The CHC was active for three years. When it was dissolved the rich material was transferred to Israel and stored in the Yad Vashem Archives, catalogued under the archival collection M-1. The folklore collection including the recordings is in the M1 PF subunit.

The recordings were transferred first in the early 1980’s to RR tapes by the National Sound Archives of the National Library in Jerusalem. At the beginning of the 21st century the recordings were transferred to a digital format and editing for listening.

The recordings contain 60 songs, mostly in Yiddish with no accompaniment. For most of them there is no record of the performer’s name, and the lyrics of the songs are also not included in the unit. 20 songs from the collection are presented in this site.

After the war Kaczerginski continued to write and record new songs. One of them, “Geshen” (It Happened), a song written in response to the Exodus 1947 affair, with music by Sigmund Berland, is included in the site.

While living in Paris, Kaczerginski published five of his books and other poems and works. Among his publications was the landmark collection “Lider fun di getos un lagern” (Songs from the Ghettos and Camps), 1948, including 236 Yiddish song lyrics and 100 melodies, published in New York in 1948.

In 1948 he visited New York and lectured to the Jewish communities there for two month. In the beginning of 1950 Kaczerginski visited Israel and considered moving there, but he was offered a job by the Argentinian branch of the Jewish Congress and moved to Argentina.

In Argentina he continued to write and publish. He composed the song “Zol Shoyn Kumen di Geula” (Let Salvation Come) set to music attributed to Rabbi Kook. He continued to lecture in Argentina and abroad.

In April 1954, Kaczerginski died in a plane crash while returning from lecturing in Mendoza. Immediately after his death a memorial book was published for him, in which some of his songs and writings that had not been previously released were first published.

Shmerke Kaczerginski greatly contributed to the fields of Holocaust documentation and research. His work, which focused on folklore, stories and songs, bears witness to Jewish steadfastness during the Holocaust period.