- Mendel Grossman, With a Camera in the Ghetto, Ghetto Fighters’ House and HaKibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House, 1970. p 101.

- Zalman Gradowski, September 6, 1944; Resistance: Havi Ben-Sasson, Shlomit Dunkelblum-Steiner, Yad Vashem, 2004.

- Abraham Sutzkever, Vilna Ghetto, September 12, 1943.

- From the Oneg Shabbat Archives.

- Shimon Huberband, Kiddush Hashem, 1909-1942. Yeshiva University Press, p. 252.

- Ringelblum, I, pp. 359-360.

- Documents on the Holocaust, Yad Vashem Archives, JM/219/3.

- Documents on the Holocaust, Yad Vashem Archives, JM/219/3.

- Documents on the Holocaust, Yad Vashem Archives, JM/215/1.

Grades: 10 through 12

Duration: In this lesson plan, we have included a large selection of resources related to unarmed resistance during the Holocaust. The teacher can decide how to utilize the subject matter presented here in the time available.

Introduction

During the Second World War, as Nazi Germany invaded Europe, Jewish people who had lived there for centuries were removed by German soldiers and their collaborators from their homes and deported to ghettos and camps. There, they endeavored to preserve their dignity despite the insurmountable circumstances.

In an effort to preserve their identity as human beings, they attempted to maintain their family life and cultural traditions. This was an attempt to not only resist losing their individuality but also a strong desire to retain family life, professions, dignity, and their very existence.

During this period a new concept was created in the ghettos and camps called the “sanctification of life” or “uberleben” (“to outlive”). This meant that each individual would do everything possible to foil the Nazis’ attempt to destroy the Jewish people as a community and as individuals.

A common theme running through these mostly unrelated occurrences was the belief that physical survival carried a spiritual element as well. One needed an additional goal or belief to cling to in order to draw the inner strength to survive.

During the Holocaust there were many types of resistance. The use of weapons, partisan activity, and planned attacks on the Nazis was known as armed resistance. There were also many examples of unarmed, cultural, or spiritual resistance. The creation of schools in the ghettos, writing songs, preparing musical activities, drawing, painting, keeping diaries, and maintaining religious customs, helped Jewish people grapple with the physical terror they were living with on a daily basis.

Didactive Objectives

- To lead high school students into a more nuanced understanding of a few of the various other forms of resistance that were employed by Jews in different contexts during the Holocaust.

- Students will understand the dire situation of Jews living in ghettos and camps.

- Students will learn how Jews in ghettos tried to survive the dehumanization process of their tormentors by applying various methods of resistance.

- Students will discuss the dilemmas and risks taken by Jews in order to fulfill their religious obligations.

- Students will learn about personal stories of ordinary individuals in the ghetto.

Resistance with the Camera

“Mendel takes out his camera. No more flowers, clouds, natures, stills, or landscapes. Amid the horror all around him he has found his destiny: to photograph and leave behind a testimony for all generations about the great tragedy unfolding before his eyes.”1

Jews were forbidden to own cameras in ghettos throughout Eastern Europe. However, some Jewish photographers were hired by the Judenrat (Jewish Council) in the Lodz Ghetto to photograph official documents, and to document official ghetto activities. In this capacity some were able to also secretly record the terrible conditions and occurrences that took place in the Lodz Ghetto. In this unauthorized form of resistance they recorded and captured the brutality of Jewish life as well as the various ways in which ghetto residents attempted to continue with their daily life, as they had practiced before they were incarcerated in the ghetto.

Mendel Grossman, a photographer in the Lodz Ghetto in Poland, risked his life to secretly document on film the awful situation there. The Germans forbade Jews to photograph in the ghetto. Grossman worked in the ghetto's statistics department, working for the Judenrat photographing official documents and documenting official ghetto activities. He had access to photography equipment and was allowed to keep a camera. He photographed thousands of scenes of ghetto life from 1940 until its liquidation in September, 1944. His camera was hidden in the lining of his coat pockets, and whenever he saw something he wanted to photograph, he opened his coat slightly and took the images. Grossman died on a death march at the age of 32, but many of his photographs were retrieved after the Holocaust.

A collection of several hundred of Grossman's photographs is available for viewing online. Search for the term "Mendel Grossman" on the Yad Vashem Online Photo Archive.

George Kadish (born Zvi Hirsch Kadushin) worked in the Kovno Ghetto, and repaired x-ray machines in Kovno for the Nazis. As such, he was able to obtain film and develop negatives at the German military hospital. He successfully photographed various scenes of life and its difficulties in the Kovno Ghetto. Kadish constructed cameras with which he could photograph through the buttonhole of his coat or over a window sill. He captured the final days of the Kovno Ghetto as it burned to the ground in 1944. Following liberation, he returned and retrieved his collection of photographs.

Discussion

- Why was it so important for Jewish photographers to capture life in the ghetto on film?

- The photograph on the left depicts people lining up for food in the Lodz Ghetto. The lady in the photograph is Mendel Grossman’s sister, Rozka Grossman. What do you think Grossman was trying to document and why?

- How does knowing the name of Mendel Grossman’s sister personalize the Holocaust for you?

- The photograph on the right shows Mendel Grossman openly taking a photo in the Lodz Ghetto. Why was it so risky for Grossman to take photographs in this way?

- Most of the images in Holocaust museums around the world today come from German sources. However, photographs taken by Grossman in Lodz, and Kadish in Kovno, are exceptions to the rule. How does this fact contribute to the importance of the photographic legacy left to us by Kadish and Grossman?

- 1. 1

Resistance through Letters

Many victims deported to their deaths in cattle cars were sometimes able to throw notes out of the small window of the moving train, or even before they boarded the train.

Look at the photograph on the right and consider the following:

Questions to the Students

- Why do you think this woman was hastily writing a letter before she was deported?

- Does her crouching position of writing help describe her extreme circumstances?

Zalman Gradowski was one of the Sonderkommando in Auschwitz-Birkenau. They were forced to operate the gas chambers and burn bodies of those Jewish victims after they had been gassed. Members of the Sonderkommando together with other prisoners succeeded in blowing up one of the crematoria. Before this courageous act, Gradowski managed to bury some papers, which were found after liberation. He wrote the following:

“Dear finder, search every part of the ground. Buried in it are dozens of documents of others, and mine, which shed light on everything that happened here. As for us, we have lost any hope of every reaching the day of liberation. The future will judge us on the basis of this evidence. May the world understand some small part of the tragic world in which we lived.” 2

Question

Why was it important to Zalman Gradowski to leave a written testimony behind?

Discussion

In the extermination camp Auschwitz-Birkenau it was virtually impossible to find a pencil to write with and paper to write on, yet Gradowski managed to scribble a last note before his death. Discuss how the above letter from Gradowski can be used to combat Holocaust denial today.

- 2. 2

Resistance through Poetry

Before addressing this section of the lesson plan we recommend reading the three points of historical information below.

- Romm’s Printing Works in Vilna had been printing traditional Jewish texts for several centuries before the Second World War. Vilna was a center of Jewish learning and publishing and was recognized as such in the Jewish world.

- The famous Babylonian Talmud is a vast collection of explanations of the Bible, legal rulings, and discussions among the Rabbis which was compiled in the fourth century C.E. in Babylonia. This large work is an example of material that was printed in Romm’s Printing Works.

- Jerusalem was the capital of the Israelite state in antiquity, and is the capital of the modern State of Israel today. The city was destroyed in the sixth century B.C.E. by the Babylonians and again in the first century C.E. by the Romans. At that point the seven-branched menorah (candelabrum) that adorned the Temple was taken to Rome by Roman soldiers.

Read the following poem written by Abraham Sutzkever in September, 1943, while he was in the Vilna Ghetto and relate to the questions below.

The Leaden Plates of Romm’s Printing Works

/ Abraham Sutzkever

Like fingers reaching out between the bars

To seize the bright air of freedom

We moved through the night to steal

The leaden plates of Romm’s Printing Works

Dreamers who had to become soldiers

We converted spirit of lead into bullets.

As once again we lifted the seal

To enter into the shelter of the ancient cave,

Armored with shadow, lit by lamps,

We spilled the letters – line after line –

Just as our forefathers in the Temple

Poured the oil into the festive menorahs.

By the casting of bullets the lead

Illumined thoughts – letter after letter melted.

One molten line from Babylon, another

From Poland, flowed into the same mold.

Jewish bravery once hidden in words

Must now strike back with shot!

Whoever saw this ammunition strapped round

The brave Jewish boys in the ghetto,

Saw Jerusalem struggling for life,

The fall of those granite walls.

Whoever understood the fiery words

Recognized their voices in his heart.3

Questions

- The poem describes an actual episode that occurred during the German occupation of Vilna. Outline the main points of the secret activity described.

- “Dreamers who had to become soldiers” (first verse) refers to the transformation of the young people active in the Jewish youth movements. Describe the changes they went through.

- In the second verse, the poet makes a comparison of the actions in the ghetto to what “our forefathers in the Temple” did. How do you understand this comparison?

- What “molten lines” are being referred to in the third verse?

- Another transformation is created at the end of this verse. Explain it.

- In the last verse what does Jerusalem represent?

Points for Class Discussion: Some Concluding Thoughts About the Poem

- How does the poem link spiritual and physical resistance during the Holocaust?

- Does the very act of writing this poem in the midst of the Holocaust provide us with an example of spiritual resistance, and why?

About twenty-five years after the end of the Second World War, Holocaust survivor Dan Pagis, who became one of the leading post-Holocaust poets, wrote the following poem. Read the poem and relate to the questions below.

Written in Pencil in the Sealed Railway-Car

/ Dan Pagis

here in this carload

I am eve

with abel my son

if you see my other son

cain son of man

tell him I

Questions

- The short six lines of the above poem present the first murder on earth in the first universal family of Adam and Eve. How does the poet link this story from the Bible to the Holocaust?

- The message that Eve wants to convey is unfinished in the last line of the poem. Refer back to the photograph of the young woman hastily writing a last note to someone. Does the photograph help you imagine what Eve might have wanted to convey in the poem? Try and complete the message for Eve.

- 3. 3

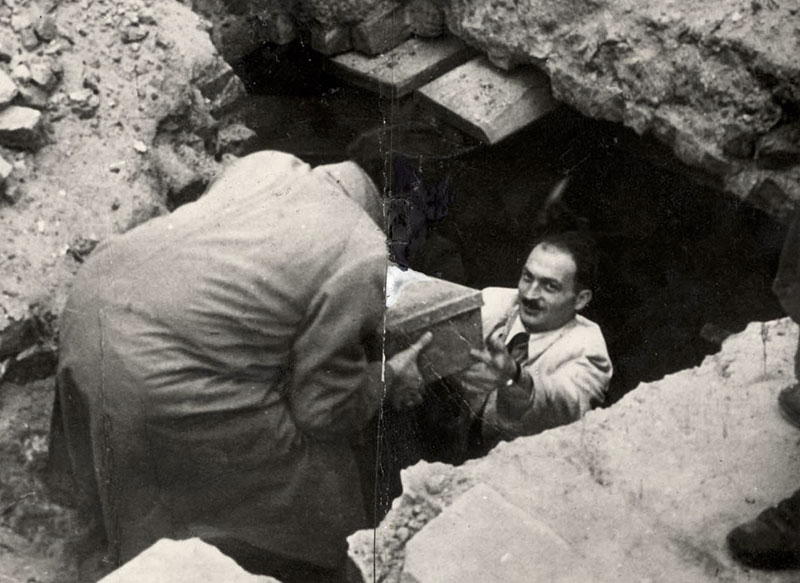

Resistance through Documentation: The Oneg Shabbat Archive

"It must all be recorded with not a single fact omitted. And when the time comes – as it surely will – let the world read and know what the murderers have done." 4

The secret Oneg Shabbat archive was founded and directed by historian Emanuel Ringelblum. In November, 1940 the Jews of Warsaw were forced into a ghetto. At that point, Ringelblum and his colleagues decided to turn the archive into an organized operation that would include tens of historians, writers, and teachers. The main goals of this clandestine project were to document the events taking place within the Warsaw Ghetto and all over Poland; to gather items of historical value; and to record the personal testimony of Jews who had been released from prisoner-of-war and forced labor camps, and that of Jewish refugees from all over Poland who had reached Warsaw.

One of the many contributors was Rabbi Shimon Huberband, a young Jewish scholar and historian. His materials deal with the cruelty of the Nazis against the Jewish population of various Polish cities and towns. He describes the destruction of synagogues, homes, Jewish religious objects and cemeteries, which he witnessed personally. After the terrible and tragic loss of his wife, young son, and father-in-law in a German air raid, he left Piotrokow and went to live in the Warsaw Ghetto, where he recorded every aspect of ghetto life, including religious life, cultural activities, and examples of heroic self-sacrifice. On August 18, at the age of thirty-four, he was deported to the Treblinka extermination camp, along with his second wife.

Please have one of your students read aloud the following primary source.

“In September, 1939, as soon as the evil ones entered the city of Bedzin, they encircled the Jewish quarter and the synagogue. They then set fire to the synagogue and the adjacent houses. When the Jews ran out of their houses, they were shot dead on the spot. Nevertheless, a group of Jews led by Mr. Shlezinger, his son, and his son-in-law dashed inside the synagogue while the sanctuary was in flames. Despite the blaze on all sides, they reached the holy ark and managed to save two Torah scrolls each, one scroll in each arm; but as they reached the door of the burning synagogue, they were shot dead by the evil ones. They died as martyrs. May their memory be blessed, and may the Lord avenge their blood.” 5

Questions

- Why was it so vital for the Ringleblum Archives (named "Oneg Shabbat") to be documented for posterity?

- To whom is Huberband referring when he speaks about “the evil ones?”

- Why would people sacrifice their lives in order to rescue religious artifacts?

The Female Couriers of the Underground Youth Movement, May 19, 1942

The Jewish youth movements active in the various ghettos of Poland embarked upon serious activities, such as organizing study courses, seminars, ideological workshops, and others. They were also in charge of publishing the underground newspapers, and in Warsaw, the youth movements set up a courier network to keep in contact with other ghettos.

Ask one of your students to read the following document written in May, 1942.

“The heroic girls, Chajka [Grosman], Frumke [Plotnicka] and others – theirs is a story that calls for the pen of a great writer. They are venturesome, courageous girls who travel here and there across Poland to cities and towns, carrying Aryan papers which describe them as Polish or Ukrainian. One of them even wears a cross, which she never leaves off and misses when she is in the ghetto. Day by day they face the greatest dangers, relying completely on their Aryan appearance and the kerchiefs they tie around their heads. They accept the most dangerous missions and carry them out without a murmur, without a moment's hesitation. If there is need for someone to travel to Vilna, Bialystok, Lvov, Kowel, Lublin, Czestochowa, or Radom to smuggle in such forbidden things as illegal publications, goods, money, they do it all as though it were the most natural thing. If there are comrades to be rescued from Vilna, Lublin, or other cities, they take the job on themselves. Nothing deters them, nothing stops them. If it is necessary to make friends with the German responsible for a train so as to travel beyond the borders of the Government-General, which is allowed only for people with special permits, they do it quite simply, as though it were their profession. They travel from city to city, where no representative of any Jewish institution has reached, such as Volhynia and Lithuania. They were the first to bring the news of the tragedy in Vilna. They were the first to take back messages of greeting and encouragement to the survivors in Vilna. How many times did they look death in the eye? How many times were they arrested and searched? But their luck held. 'Those who go on an errand of mercy will meet no evil.' With what modesty and simplicity do they deliver their reports on what they accomplished during their travels on trains where Christians, men and women, were picked up and taken away for work in Germany. Jewish women have written a shining page in the history of the present World War. The Chajkes and the Frumkes will take first place in this history. These girls do not know what it is to rest. They have hardly arrived from Czestochowa where they took forbidden goods, and in a few hours they would move on again: they do it without a moment's hesitation, and without a minute's rest.”6

Questions

- Why was it dangerous for the Jewish female couriers to travel around Poland during the Holocaust?

- What motivated the couriers to take on their dangerous missions?

- Discuss the dilemmas and dangers facing Chajke and Frumke when traveling around Poland.

- 6. 6

Jewish Political Parties and the Aims of Jewish Youth Regarding the War Situation in Poland in 1940

Despite the constraints of war, Jewish political life continued and the activities of the Jewish youth movements struggled to adapt to the demands of war.

Read the following excerpt from one of the underground newspapers circulating in the Warsaw Ghetto, dated December, 1940.

THE WORK OF A JEWISH POLITICAL PARTY FROM AN UNDERGROUND PUBLICATION, 1940

“...What should our task be in this war? Two answers were given. There were members who were of the opinion that at the present time we should occupy ourselves only with economic problems, helping the large number of members who are in difficulties, looking for means to help them, and very often to see to it that there should be a piece of bread and a bowl of soup for those in need."Another group of members considered that it was by no means the purpose of our movement to turn itself into a charitable organization and to provide aid for individuals. According to them such tasks were never our responsibility nor that of movements similar to ours, and we should not occupy ourselves with them, even though conditions have changed. We should turn to cultural activities, build up organizational cells, hold frequent discussions among the members to broaden our educational activities and make use of this time for deeper thought.”7

Questions

- What kind of aid did the first group of members provide?

- Describe the different approach of the second group.

- Now read the concluding part of this historical document:

“...And if this debate was in place a few months ago, then today, owing to the realities of the situation and the experience of more than a year, it is no longer the time for it now. All the members were right, those who said one thing and those who said the other: we are working in both directions at once, and the two views have merged into one...” 8

What happens with the passage of time between the two approaches?

Now read the following extract from one of the underground newspapers circulating in the Warsaw Ghetto, in August, 1940.

THE AIMS OF JEWISH YOUTH AT THE PRESENT TIME, FROM AN UNDERGROUND PUBLICATION, 1940

“...We, the Jewish youth, cannot free ourselves from the influence of the situation as a whole on young people in general. The war and the Nazi occupation have revealed the tragedy of our Jewish youth very sharply. What must we do in this situation? In which direction shall we turn our attention? We must arrange courses in reading and writing Yiddish, Hebrew, and in arithmetic, etc., to draw the street youth into warm surroundings, to attend as far as possible to their personal future, and to implant in them a feeling of solidarity and responsibility; and with the aid of singing and games to create a youthful atmosphere for a Jewish youth that has become old before its time......its feeling for the people must be awakened; it must be given an awareness of Socialism; it must be drawn into public activities in every part of Jewish life; enriched with the spiritual treasures which the Jewish people have created through the ages. And, finally, we must gather together the best of the Jewish youth, which has already received its education in our movement, and forge it into a cadre that is prepared for battle and that will lead the way for Jewish youth...” 9

Before addressing Question #2 below, we suggest you become familiar with information about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

Questions

- Describe at least three of the spheres of activity dealt with in this document.

- The conclusion of the given document hints at the escalating needs of the war situation. What is ‘the best of the Jewish youth’ to prepare for in the future?

- How do both documents from the Jewish political party and the Jewish youth movement show unarmed resistance?