- A Jewish Zionist youth group.

- This quote from the text of the Hagaddah (the story of the flight of the Jews from Egypt) has been repeated every year for thousands of years by Jews during celebration of the holiday of Passover.

- The Balfour Declaration of 2 November 1917 was a letter from the United Kingdom's Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour to Baron Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, for transmission to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland, stating that: “His Majesty's government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

- Esther is referring to the Red Cross’s visit to Theresienstadt on July 23, 1944. In order to convince the Red Cross that the Germans were treating the Jews well, trees and flowers were planted in this ghetto, false storefronts, cafes and bandstands were put up, and the Germans elaborately choreographed the visit to ensure that the impression given was one of comfort and normalcy. As part of their preparation for the Red Cross visit, the Germans relieved the terrible overcrowding in the ghetto by sending thousands of people to Auschwitz, where most of them were murdered.

The Kindertransport

Whilst dealing with the individual and the collective in this e-newsletter, we can understand how difficult it became to find a way to save children, as the rise of the Nazis to power made life in Germany more and more restrictive, and it was harder and harder to leave Germany.

If the community as a whole could not be saved, a way had to be found to save some of the children, even if it meant they had to leave their families behind.

As late as 1939, Recha Freier, founder of Youth Aliya, realized that it was essential to at least save as many children as possible. Although experiencing some opposition from the Jewish community in Germany, she was able, through the auspices of Youth Aliya, to send thousands of children on the Kindertransport to England. Ester Golan’s parents eventually managed to get Ester and her sister on one of the Kindertransports, but they were never to see their children again. This was the sacrifice Ester’s parents had to make.

Introduction: Ester Golan

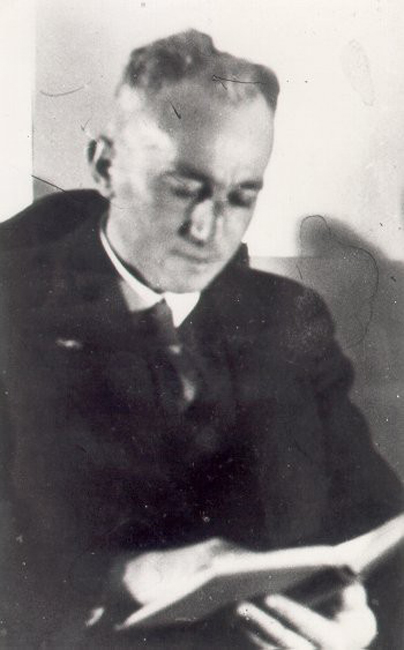

“I was born in Germany in Glogau, Silesia, in 1923 to Arno and Else Dobkowsky. I lived with my father, my mother, my elder brother Peter, my little sister Marianne, and my grandmother. My parents ran a successful store in Glogau and were able to employ a resident maid and a cook, as well as a children’s nurse. As I was growing up, there was a pleasant atmosphere and happy family lifestyle with Sunday outings with friends or relatives by foot, on bicycle or by boat along the river Oder, but before long the economic crisis came in the year 1929 and hit my family very hard. Within a short time the shop went bankrupt. My parents could no longer afford to pay the rent for the spacious apartment they were living in and moved to a much cheaper, but also much smaller one in a remote area across the bridge on the other side of the river Oder and far from the Synagogue. When my father found a good position at an insurance agency we moved back to the center of town and rented a spacious flat in Friedrich Street, a part of the town where many Jews lived as it was near to the synagogue. The few Jewish children in the vicinity were all different ages. Once a week they got religious instruction at the synagogue given by a rabbinical student.

In 1933 after Hitler’s rise to power, Jewish children were no longer admitted to the Gymnasium or Lyceum. While all the better pupils moved on, I had to stay on at the elementary school. The curriculum was basic at best and was changed to include a lot of Nazi propaganda. I was the only Jewish girl in my class. Nobody talked to me and during the break, and while others played together, I stood all by myself in the corner of the schoolyard.

Packing up to move to a much smaller place meant reducing the household and leaving behind belongings, such as furniture, curtains, books, paintings, and toys, but above all, it meant parting from the extended family, old acquaintances and friends. No sooner had we arrived, we were told to move out again, because Jews were not wanted there. We felt very lucky to find place at 16 Courbiere Street. The entrance was through the back yard. It was near Wittenberg Square and Kurfürstendamm Street, close to the Jewish cultural club.

For the remaining part of the 8th grade, until Easter 1938, I went to a Jewish school in Klopstock Street. I did not know a soul in Berlin and it was hard to make new friends.

As the situation for Jews got worse, my mother arranged for my grandmother to leave Germany by ship for Portugal. This was on 29 January, 1939. It was very hard for my mother to part with her mother, who she would never see again.

After Crystal Night (Kristallnacht), on November 9, 1938, I was interviewed for, but turned down, by Youth Aliyah, because I was underweight. I desperately wanted to join my brother Peter, who had already left Germany in 1937 and was already in Palestine. Eventually, in April 1939, I was put on the Kindertransport, and sent to England. I was actually sent to Whittingham Castle, on Lord Balfour’s estate in Scotland, as part of Youth Aliya on hachshara (agricultural preparation program), with Habonim1. We were really refugees on Hachshara. Jewish or non-Jewish families took in the younger children. I was already 15, and nobody wanted a 15-year old. So I had to look out for myself. It was difficult to be separated from my family. My sister Marianne was sent to a Jewish family in London in 1939.

My family had wanted to leave Germany together, but unfortunately we could not get a family visa. My parents wanted to leave Germany for Palestine. My mother was a Zionist, but they didn’t have enough money to leave. My grandparents dreamed of going to Zion – “next year in Jerusalem”.2 After the Balfour Declaration3, my mother’s generation wanted to live that dream. By saving her family, my mother ensured the continuation of her family.

Only my parents were left in Berlin. In October 1942, they were sent to Theresienstadt, where my father perished in 1943.

- 1. A Jewish Zionist youth group.

- 2. This quote from the text of the Hagaddah (the story of the flight of the Jews from Egypt) has been repeated every year for thousands of years by Jews during celebration of the holiday of Passover.

- 3. The Balfour Declaration of 2 November 1917 was a letter from the United Kingdom's Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour to Baron Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, for transmission to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland, stating that: “His Majesty's government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

I came to Palestine in 1945. We were immediately sent to the detention camp in Atlit. Although we had certificates, others like Rabbi Lau who was on the same boat didn’t, so we were all sent to Atlit detention camp by the British, to be processed. On the boat were 1,200 survivors from Buchenwald and Bergen Belsen.

In 1946 I found out that my mother had been sent to Auschwitz, where she perished in 1944. When the Red Cross came to visit Theresienstadt4, a lot of people, including my mother, were sent to Auschwitz.

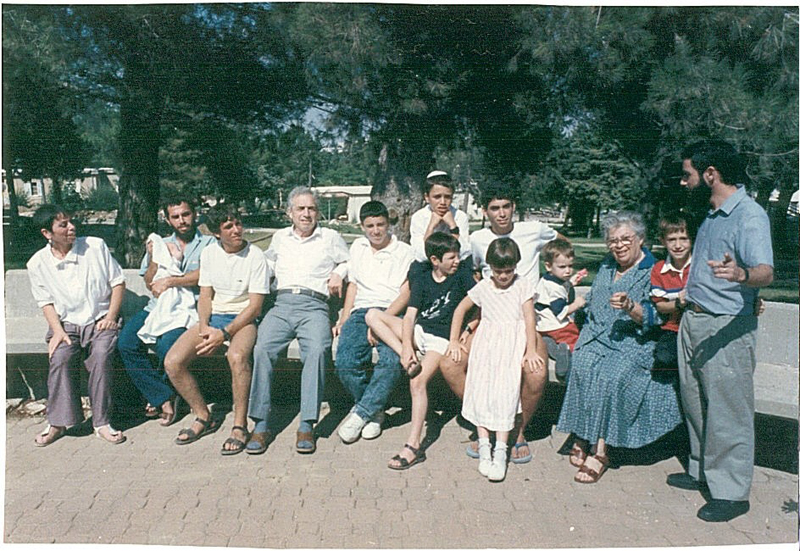

I married twice and after my children left home, I decided to go to university to study.

In 2002 my grandson who was serving in the Israeli army was killed in Jenin. This for me was the Shoah, not only then and there, but here and now.

I stopped writing my poetry after that.

Ester’s Poetry

Tell me about your poetry. Your poetry is very powerful. Where does it come from?

It comes from several sources. Firstly, I did come from a very beautiful and secure and solid family background. My parents loved each other and I had a wonderful early childhood until I was six - until the big economic crisis in 1929. In 1933 Hitler came to power and 1939 I left home and everything changed. Leaving home – I wasn’t sent away, I left with the words “Li’ hitraot b’artzenu”, “See you again in our land”, hoping we would all come here [to Israel]. Eventually after I went to university, I was emotionally mature enough to study and had reached the age when I understood who I was and what had become of me and my family, people and country. I began to write. It all came together as I said, after I started university – the book of my mother’s letters, painting and poetry.

It just comes into your head spontaneously?

Some of it just by itself, and I also went to a course for poetry writing and creative writing.

It all stopped when my grandson fell.

The letters from my mother

- 4. Esther is referring to the Red Cross’s visit to Theresienstadt on July 23, 1944. In order to convince the Red Cross that the Germans were treating the Jews well, trees and flowers were planted in this ghetto, false storefronts, cafes and bandstands were put up, and the Germans elaborately choreographed the visit to ensure that the impression given was one of comfort and normalcy. As part of their preparation for the Red Cross visit, the Germans relieved the terrible overcrowding in the ghetto by sending thousands of people to Auschwitz, where most of them were murdered.

Tell me about your mother’s letters.

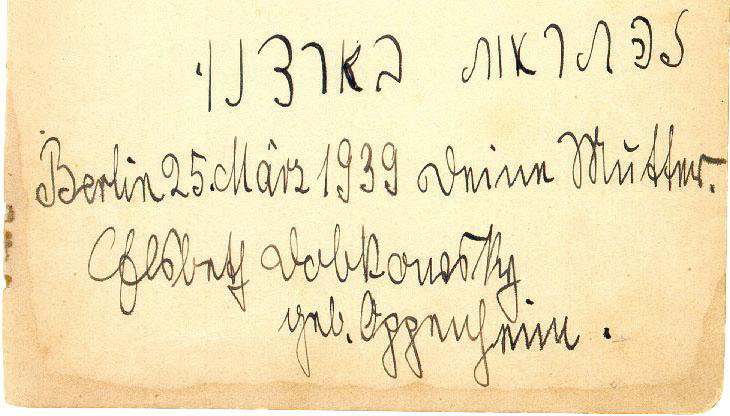

I had all the letters from my mother and I began to look for someone who could decipher the handwriting in the letters. I couldn’t find anyone who could transcribe the letters and use a computer, so I decided to take a big handkerchief and transcribe all the letters I received from my mother myself.

How did you receive these letters?

My mother wrote to me for three and a half years. The letters were written between 1939 and 1942 and sent to Scotland, via my grandmother in Portugal.

Why was it important to publish the letters from your mother?

So, when I was emotionally mature, reading these letters I suddenly understood what it was all about. Reading them at 60 and not 15, one understands a mother’s side quite differently. My mother takes a great interest in my development and encourages and helps me over the first bumps of my life. When she heard I was getting married the first time, she advised and helped me. That was one basis of being able to do what I did. Something else that encouraged me was meeting Rachel Freier, a schoolmate of my mother’s, who I visited when I came to Israel. She remembered my mother – the only person I met after I left home, who remembered my mother – she told me my mother was something special. To hear that I am like my mother was something – a very big boost.

After I managed to finish the book of letters, and the book was published, I felt better. I couldn’t have had a better memorial for my mother than this book. The letters were the last link to my parents.

Here are two poems connected to my mother’s letters.

Me and My Emotions (Jerusalem 2001)

Will I ever grow up?

Really grow up?

Will I be able to cut myself free

From a bunch of letters?

Letters that are old and faded

As I will be before long.

Are the letters the umbilical cord

That tie me to my emotions?

My emotions of being deprived,

Deprived of what?

Of being whole,

A whole human being,

A part of a whole

Part of a whole family?

To Part

I am about to part

To part with letters

The letters that are

The last link to what I was

The last link to my family,

The last link to what I craved for

Year after year

I read them

I cherished them,

I cherish what no longer is.

Can they live on

Put behind glass?

In a museum?

For you to see

For you to share

For you to know

That once upon a time

We were just like you

A whole, a loving, family.

(Ester gave all her documentation as a gift to Yad Vashem)

Which languages do you write in?

I write stories and poetry in Hebrew, German and English. Usually, I don’t translate from one language to the other.

Did you write poetry before you left Germany?

No – the painting and writing was written mainly end of the 1990’s and beginning of 2000”s. After my grandson died I stopped writing.

What does it mean to have a family after the Holocaust?

I have three children, three grandchildren and 14 great-grand children.

My son is wonderful to me; he looks after me like I would like to have looked after my mother, and how I saw my mother look after her mother. So it’s a continuation of life in a way.

My Sons and My Mother (Jerusalem, January 1996)

You my sons are to me

What I did not dare to dream of.

You care for me, as I hoped to care,

For my mother, as I saw her care for her's.

In my youth I thought,

That is how I will be,

How I will care for her

When she'll be old.

Oh, mother dear,

They did not let you live,

To be, to grow old,

To be taken care of by me.

And now it is my sons

Who care for me.

When my grandson was 16, he told me he was going to Poland the next day. I didn’t have much time, so I took him to the Valley of the Communities and I told him to always remember that his grandparents were good, loving and kind people, with values which were passed on to me and that I hope they will be passed on from generation to generation. Although my parents perished in Theresienstadt and Auschwitz, it is important to me that I have children and grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren.

Your writing is almost – am I right in saying that in a way you feel guilty?

No, not guilty. I was very attached to my mother and very few people understand that because most children from Kindertransport asked how their mother could send them away. I never said that. Here is another poem about that period of my life.

My Wings Were Clipped (26 February 2001)

When I was young

I wanted to fly

And reach out high

I was put in a cage

My wings were clipped

I managed to escape

By leaving home

With a Kindertransport

But being a refugee

My wings were clipped

I tried to escape

Blinded by love

Married at a young age

I was back in a cage

My wings were clipped

I ran to the war to fight

For the freedom for my people

In the land of the dreams of my mother

All for fear of having

My wings clipped again

Only to be caught once more

Married again

With no escape

Till death did us apart

My wings were clipped.

And when I thought that now I am free

I got caught again

In a golden cage of time

Will God grant me to make up

What could have been,

If my wings had not been

Clipped and clipped and clipped again?

You are making up time for having your wings clipped, I think. Your poems are amazing. It’s a wonderful way of being able to express your innermost feelings.

Yes, I’ve reached a very positive stage in my life thanks to my mother’s basic education in Germany. Whatever I know I know because my mother taught me. She taught me to make the most of life; to never let anything from the outside change your way of living. She was quite an amazing person.

You were alone, and yet your mother is still with you. She has been your inspiration for all your poetry?

Not has been, still is and is responsible for my being, including the poetry.

Did other poets influence your writing? Do you read other poetry?

Not really because it is something very emotional. What I wrote is really to try to put my emotions into words. But those are my emotions and I try to find words for them. Reading other peoples’ emotions isn’t what helped me move on.

Do you find writing it down is easier than speaking it out?

Oh yes.

Your poetry expresses your innermost thoughts and feelings. We just talked about that. Was there a time when you could only write it down and not verbally express yourself?

No, I cried for 30 years instead.

Do you want to comment about Theodore Adorno. He said that anyone who wrote poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. What’s your answer to that?

Let him think what he likes. There are different attitudes to the Holocaust.

How do you use your poetry in Holocaust education?

I read quite frequently to groups of all ages and backgrounds.

What is the reaction of the students? Do they ask if they can use the poetry? Do they ask you questions?

They are numb! They are amazed that I talk about it without crying. They can only listen to me if I speak with them, not to them. I ask them how old they are or what their name is. I tell them that once upon a time I was their age. I make it personal. I speak with them and when I read some of the poems, I read it with them also, as part of my story. They are so stunned by the story that sometimes they cannot get up, so I read a poem or two and they start breathing again, and sometimes I have to go and console one or two of the students who are crying. I allow people into my life if they can identify with my story. My story is appropriate for any age and mothers, parents, children and teenagers can identify with my story.

It seems to me that the main focus of your poetry is your mother and you are commemorating your mother and what happened. That is your form of commemoration?

Yes, most certainly. It’s more than that really. The poetry is part of my commemoration - the fact that I share the story with other people. I usually start off when I speak to people and say to them “I want to share with you my story” and not “I want to tell you”. I think the sharing is the part and I also share the poems with them and that is the commemoration because if you tell them about it, it washes away, but if you share it with them something remains.